Intrigued by a lithograph titled ‘The Five Celestial Musicians of Hindu Mythology’ by Rajah Sir SM Tagore, Prof B.N. Goswamy records the circles that this picture made him run, and the joy of having worked something out: finally. (Photo courtesy: The Tribune)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

I doubt if this will add greatly to anyone’s information or pleasure, but I am unable to resist the temptation of recording the circles that a picture made me run, and the joy of having worked something out: finally.

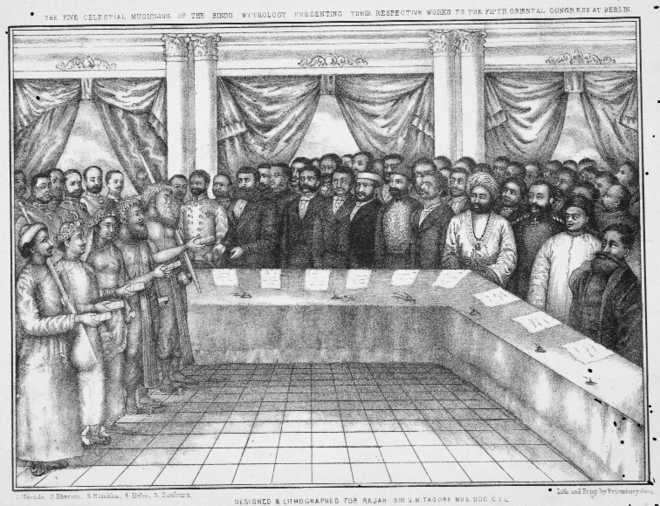

Some years back, I was intrigued by a lithograph—simply put, a lithograph is a print on paper made from a design or drawing originally done on stone—in the collection of the Chandigarh Museum. It showed a large group of mostly European looking scholars, gazing somewhat quizzically at five persons standing before them—‘The Five Celestial Musicians of Hindu Mythology’—at the Fifth Oriental Congress at Berlin. I had found the image mildly amusing then, for the five persons, all curiously dressed, all looking a bit uneasy, each holding a manuscript in hand, were identified by names, which read: starting from the left, Narada, Bharata, Rambha, Huhu and Tumburu. Two persons were heavily bearded; two, including the only woman in the group, wore crowns; one of them, identified as Narada, and another as Tumburu, held stringed musical instruments in their hands. I found the whole thing amusing for nothing corresponded to any figure that one knew from early Indian art: of these, at least Narada was very familiar to me for he, the deva-rishi, appears in countless Indian paintings treating of sacred texts of the past, hair coiled up, double-gourded veena in hand, and for the most part flying through the air: this figure in the lithograph looked like a reasonably dressed Bengali musician come visiting. But, after having noticed this, I had moved on.

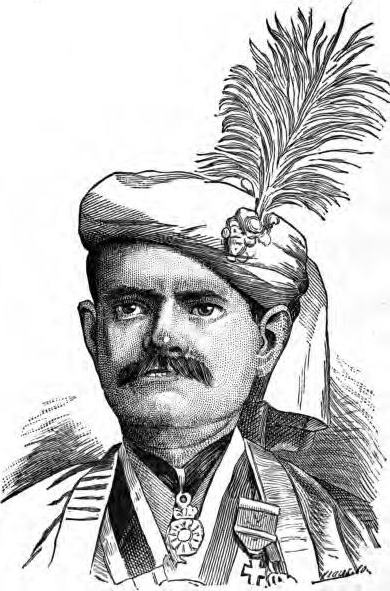

Somehow—I do not exactly recall how—the same lithograph surfaced before me again, quite recently, and I decided to spend a little more time on it. The puzzlement remained, but I tried honestly to make some sense of it. All the words printed on the lithograph were in English: the title above the image, as also the names of the ‘celestial musicians’, and another line printed at bottom. The bottom line, which I had omitted to notice the last time, read: ‘Designed and Lithographed for Rajah Sir SM Tagore Doc.Mus.C.I.E.’; a little further off, in the right hand corner were the words: ‘Lith. and Print by Kristohurry Doss’. Sourindra Mohan Tagore, the ‘Rajah’ of the caption, I knew something about. A scion of the Tagore family, he was deeply interested in Indian music, and in his own times (1840–1914) was widely regarded as a great authority on it, having written impressive and well-documented books—one of which ran into more than 30 editions—and receiving honours from country after country. A scholar of Sanskrit too, he was knighted by the Queen of England for his scholarship and his extremely wide range of interests. But how was he involved with the 1871 Orientalists’ Congress in Berlin? Did he—candidly the thought did go through my mind—attend the Congress and actually took with him, to present there, five persons dressed up as Narada, Bharata, Rambha and others? It could have been dramatic—theatrical even—but surely this was not so, I decided.

In my confusion, I decided to approach Professor Mukund Lath at Jaipur—eminent scholar and a great expert on music—to see if he could clarify things for me. I naturally attached a photograph of the lithograph and asked him questions about it. Most kindly, he wrote back to say that he too was greatly intrigued: as much by the lithograph as by the choice of the five ‘celestial’ figures. Close on the heels of this, however, he wrote another mail, saying he had worked out the ‘Rajah’s’ choice of the five figures. They represented, he thought, the different performing arts of India: Narada stood for music; Bharata for theatre, Rambha for dance, and the two gandharvas, Huhu and Tumburu, for percussion and string instruments. But he also added that in his knowledge the Rajah did not go to Berlin in that year: instead he sent this lithograph accompanied by a book of about 30 pages consisting of ‘an allegorical paper’, ‘in acknowledgement of the compliment paid to him (by inviting him)’. Professor Lath, most kindly, also mentioned that the book, and other papers, is accessible on ‘the internet site named Sahapedia’. All this was extremely useful, of course.

Also see | Sourindro Mohun Tagore

It so happens that I know some people responsible for Sahapedia, that fine internet site, including Dr Sudha Gopalakrishnan who founded it. So, my search led me to address myself to her and, quite like Professor Lath, she responded very quickly, and kindly, having dug out the material relevant to the Tagore ‘Rajah’s book and, in addition, drawing my attention, through a young colleague of hers, to an image gallery on the internet in which were featured illustrations of ragas and raginis (on which the ‘Rajah’ had been writing over the years). Those Ragamala images, all in the form of coloured lithographs, and most of them following a different iconography for ragas and raginis than the ones generally known, were a revelation again: for here they were, the work possibly also of ‘Kristohurry Doss’ who designed the lithograph with which I started. In some ways, my search had come to an end.

It is unlikely to be of interest to many people, but I might go looking for Kristohurry Doss next.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.