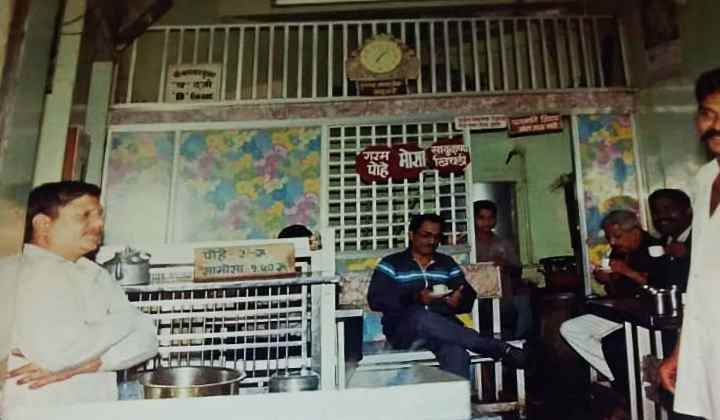

Drinking tea is a part of everyday existence for most Indians. But, not known to many, tea became a popular beverage after a push from the British East India Company in the late-eighteenth century. Over the years, small thelas and hole-in-the-wall teashops have ensured its continuity—such as the amruttulyas of Pune. On International Tea Day, it is important to recognise the contribution of the many small institutions, built over generations, to this cultural heritage. (In pic: Aadhyaa Amruttulya; Photo courtesy: Sahapedia Pune Cultural Mapping Project)

Tea-drinking in India, currently the world’s largest tea consumer, gained popularity because of the British East India Company as recent as the late-eighteenth century. In spite of its relatively nascent rise in popularity, tea joints across the country are romanticised, quite like beer pubs in the West. Part of this cultural heritage is the contribution of the many small institutions built over generations.

From street-side makeshift stalls to piquant brick-and-mortar Irani chai shops, these desi joints have made tea drinking not just a personal but a public act, evolving over time. One such example is that of the amruttulyas (amrut meaning nectar and tulya meaning comparable), lesser-known across the country but revered in Pune.

Also read | The Indian Constitution: Not Just Any Piece of Paper

Amruttulyas are crammed shops accommodating a maximum of 10–12 people seated across three–four tables and a katta (seat made of stone or wood) in front of the shop. There is a raised wooden platform at the entrance where the owner sits and does his daily prayers, brews tea, stores the petty cash and runs calculations on a chalk slate. The tea owes its peculiar taste to the brass vessel it is made in, seasoned with spices ground in a mortar pestle as per the owner’s quirks and mixed with very sugary milk thickened by prolonged brewing on the stove. The brewers prefer to use a cloth instead of the common strainer because they believe the flavour seeps through better.

The First Flush

The story of the amruttulyas that pop casually across Pune’s aged streets traces its roots to the 1880s, in the Narta village in Shriman (now Bhinmal) tehsil of Rajasthan. Distraught by the drought, a Rajasthani couple, Vishwanath Pannalal Ojha and his wife, walked about 900km from their village to Pune, recounts his great-grandson, Rahul Nartekar. On their arrival, they changed their surname to ‘Nartekar’ (a Marathi-Brahmin surname). In time, Vishwanath Pannalal and his brother Bhavanishankar bought a small shop in Ravivar Peth, and started selling bhaang (an intoxicant extracted from the cannabis plant, which grows extensively with no legal restrictions in Rajasthan to date). One could speculate that the term ‘amrut-tulya’ could have originated there.

Growing oversight of the British government’s narcotics cell led the family to shift to selling sweets and chai, under the name Rajasthan Sweet Home. With the chai gaining prominence, the first ‘Aadhya Amruttulya’ was started on July 27, 1924, just when the current Pune railway station structure was built. Thereafter, amruttulyas grew rapidly with more families migrating, and the growing Rajasthani community in Pune supporting each other in the opening up of more such teashops.

Related | Pune Culture Mapping

It is interesting to note, especially now when there is much conversation about migrant populations, how a migrant from Rajasthan in the 1880s started Pune’s obsession for tea. But this was no casual accident. Prior to the amruttulyas, chai shops in the city were usually owned by the Irani Muslims. In this context, Aadhya—owned by a Shriman Brahmin who wore the Marathi identity up his sleeve—kickstarted the acceptance of sitting and drinking tea in public. This is significant as until then the dominant Maharashtrian Brahmin community considered this sinful. The Shriman Brahmins, like their Marathi counterparts, were devout and named their shops beginning with ‘Om’ suffixed with Hindu god names such as Amruteshwar, Jabareshwar, Manakeshwar, Narmadeshwar. All Rajasthani-owned shops recruited Marathi helpers, mostly from the Konkan regions.

Complex Blends

In the 1950s, Maharashtrians started their own amruttulyas—ending the monopoly of the Rajasthani community. These gained ground with the popularity of the Ambadas Lokaseva Upahargruha, a 24/7 teashop that attracted actors from the film and theatre circles. A distinguishing feature of these shops was selling of popular Maharashtrian treats like vada, misal, papdi and pav sample.

Over time, amruttulyas have become a more inclusive public space, although it predominantly attracts male customers. Today, they represent a microcosm of the city—students, hawkers, labourers, artistes, and others. Businessmen like Milind Darvekar talk about closing many of their business deals here, while filmmaker Umesh Kulkarni fondly recalls visiting just to overhear the mundane conversations of huddled strangers.

Fading Away

The present is also marked by their slow disappearance, from 750 to 400 shops over the last decade, shares Nartekar. A labour-intensive operation sustained by deep relationships with customers and employees, the amruttulyas have limited takers among the educated youth of the owner families. Add to this, as Hitesh Mukund Ojha of Ambuka Bhuvan says, the dwindling profit margins on one cup of chai and mushrooming of the many handcarts selling chai at half the price, making the going tougher.

Also see | The Birth of Experimental Theatre in Bombay: In Conversation with Saryu Doshi

Some argue that amruttulyas and their cultural heritage is a thing of the past, and patronising them over the growing tea café culture is be foolhardy. While tea chains like Yewale or Wagh Bakri café have their own place in the market, what the amruttulyas provide is very distinct. There is a natural air of trust between owners and customers who pick their cream rolls from the barani (vase), drink their fresh cuppa at their own pace and pay at the end. They foster a sense of community and a shared experience, something that we recognise valuable in COVID times.

A message scribbled on notice boards across many amruttulyas reads, ‘Chahachi vel naste, pan velela chaha lagto’ (There is no right time to have tea, but you need tea at the right time). We might have one World Tea Day, but there is a world of teas to be sipped every day at these kattas.

This article was also published on TheIndianExpress.com.