‘Then there is Tikse, wonderful Tikse, with its gompa, perhaps the most picturesque and beautiful in all Ladakh, whose hundred buildings descend in steps from the top of a great ridge of rock right down to the plain below, which bristles with a forest of chorten.’

- Giotto Danielli (1933: 275–76)

I. Introduction

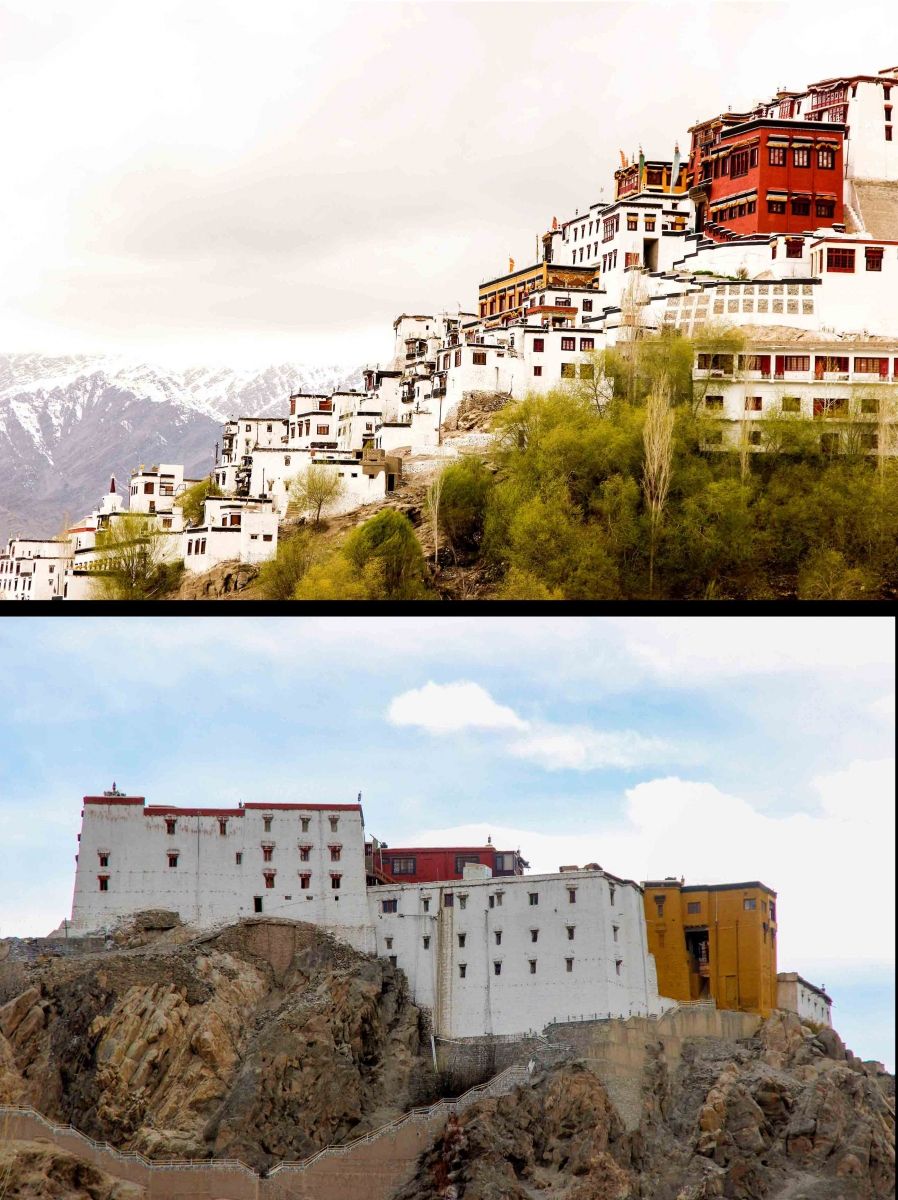

Thiksey Monastery is one of the largest monasteries in Ladakh and is located about 19 Km from Leh on the Leh–Manali highway. It is often compared with the Potala Palace in Lhasa, on account of its general appearance, as it occupies the entire south face of a hill (Fig. 1). At the top of the monastery are buildings painted red and yellow followed by a tumbledown of small one-room box-like houses for the lamas, which are punctuated by large rectangular buildings at intervals. Today, the entire monastery area is well laid-out with a large walled compound at the foothill and several small structures to hold the annual Photang[1]. The route leading up to the monastery is lined with chortens (stupas) and mane (prayer) walls.

Built around the 16th century, Thiksey is the main centre for a small sub-order of the Gelugpa sect with a resident Kushok (head lama) who runs the order with a firm hand, in strict accordance with the Vinaya texts. It houses about 80 monks on the premises and also holds one of the largest nunneries in Ladakh. However, before the 16th century CE, the Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) monastery structure was a part of the defence establishment for the Namgyal rulers, in Shey.

The monastery manages the ancient site of Nyarma (located a few kilometres away) and also part of the Shey chorten field[2]. A school for novices and a Tibetan medicine centre are also located within the monastery premises. It also houses a large number of important manuscripts including the Kangyur, placed in a lhakhang of the same name.

Thiksey was the first Gelugpa establishment in Ladakh and the founders following the teachings of the great reformer, Tsonkhapa, actively worked to extend the influence of the Gelugpa teachings throughout Ladakh. This process was aided with the support of the royal family which resulted in extending and building establishments in remote areas. Some of the important monasteries and sites administered by Thiksey are Nyarma, Diskit, Hunder, Insta and Stagmo.

II. Brief History

The history of Thiksey is closely linked to the introduction of the Gelugpa order in Ladakh. This introduction was initiated by Tsonkhapa (1357–1419), the great reformer in his lifetime. In order to propagate the sect’s teachings, he sent envoys bearing gifts to the king, Ras Bumde (Grags-bum-de). Ras Bumde had already heard of Tsonkhapa and his reforms and the reformer’s gifts served to impress him further. Bumde, thereafter, offered Petub as a centre for the Gelugpa establishment. He also initiated the construction of a monastery in Petub as an offering to Tsonkhapa (Petech 1977: 22).

After Ras Bumde, his son Lodro Togden (Blo gros mc’og ldan; 1440–1470) continued his support to the Gelugpa order. He sent gifts to the first Dalai Lama (rGyal ba), besides patronizing the Gelugpa scholar Sherab Tzangpo (Shes-rab-bzangpo), a student of Khedrup je who was one of the two main disciples of Tsonkhapa (Petech 1977: 23). Sherab Tzangpo was popular and the king’s patronage helped him establish a monastery at Stagmo.

It was Pon Sherab Raspa (dPal-Ses-rab-grags-pa), the nephew of Sherab Tzangpo, who established Thiksey in 1433 and managed to increase the Gelugpa following in Ladakh (Petech 1977: 168). According to a popular narrative, the location for setting up the new monastery at Thiksey was revealed through a mystical episode. After performing sacred rituals at Stagmo temple, the lamas (uncle and nephew) took the ritual torma (figures and objects made of flour) to be disposed of. As they were approaching the spot, two crows snatched the vessel with the torma and flew away. The lamas, searching for the torma, found them laid out, undamaged, on a hill above Thiksey village. Interpreting this mystical event as a divine directive to set up a monastery to propagate the teachings of Tsonkhapa and the Gelugpa order, the first temples were constructed at Thiksey.

Royal support to the Gelugpa establishments continued with Jamyang Namgyal (1595–1616), who after his release from Skardu, along with his wife Gyal Khatun, became a staunch supporter of the Gelugpa order. He made regular offerings to Jokhang in Lhasa and the Dalai Lama in the Dripung Monastery. He also handed over most of the old temples and monasteries such as the ones at Alchi, Saspol and Nyarma to the care of the Gelugpa establishments at Likir, Petub and Thiksey.

Jamyang Namgyal and his wife continued their patronage to the Drukpa order in a limited fashion. However, Jamyang Namgyal was also responsible for limiting the growth of the yellow sect as he sent an invitation to Stagsan Raspa to visit his court. This small act initiated the process of Drukpa Kagyupa’s ascendance in Ladakh. Senge Namgyal, son of Jamyang Namgyal, donated large estates to the Drukpa Kagyupa order with Stagsan Raspa as the royal teacher. It is reported that Senge Namgyal wanted Thiksey to go to the Drukpa Kagyupa sect; however, Stagsan refused to accept this gift (Petech 1977: 52). The Gelugpa establishments did not recover from the combined efforts of Senge Namgyal and Stagsan Raspa in spreading the red hat doctrine and ensuring the supremacy of the Drukpa Kagyupa in the region permanently.

The first incarnate of Bakula, Jangsem Sherab Tsangpo (1395–1457), worked hard to establish the new reforms of Tsonkhapa in Ladakh. His subsequent appearances (incarnations) spread the doctrine in many parts of the region. Over the years each incarnate managed to expand the Gelugpa influence across the region.

Thiksey, since its foundation, was the primary Gelugpa institution in Ladakh, and it would appear that Petub and later Likir were also administered by the Thiksey Rinpoche in the early years. It was only in the late 19th century that a royal prince from Zanskar was appointed as the first Bakula of Petub. Thiksey also lost control of the Likir Monastery after an incarnate was found (present incarnate of Likir: Nari Rinpoche, brother of H.H. Dalai Lama)

The ninth and present incarnate Thiksey Rinpoche Ngawang Jamyang Chamba Stanzin (born in 1943) has redefined the role of a religious head. Along with Bakula Rinpoche of Petub, the Thiksey Rinpoche has actively taken on political advocacy to benefit the people of the region, irrespective of their allegiance. He has scholarly and religious accomplishments and has also served as an elected member of the Rajya Sabha (the upper house) and as a state-level minister.

Under the stewardship of Thiksey Rinpoche, the monastery infrastructure has been updated with repairs carried out in several temples and new structures added to the existing complex. Among the major visible additions is the Chamba Lhakhang (built in 1980) with the 40 feet sculpture of Maitreya and the Photang complex (built in around 2010) at the base of the hill.

III. Architecture

Rectilinear structures of various dimensions cascade down the south slope of a hill resembling a cubist collage (Fig. 2a). Thick black lines running along the roof, accentuate the dimensions of each structure. Small windows, framed with broad black bands, punctuate the overwhelming white of the buildings. The hill is crowned with buildings painted yellow and red to emphasize the hierarchy within the monastic order and signalling the nature of the buildings.

From the south, it is difficult to get a sense of the scale of individual structures; but from the north, one gets an idea of the scale of the multi-storey structures of the main monastery (Fig. 2b). It would appear that the development of the site has been iterative, with the core and earliest structures (the dukhang and the gonkhang) at the top of the hill. The additions are organic and driven by space requirements of the growing order. The structures are close to each other, often sharing common walls. The monastery complex has, besides the main temples and prayer hall, several other important spaces and dedicated temples. The Tara Lhakhang, dedicated to Tara—a principal deity, is in a medium-sized hall across the Chamba Lhakhang. The Lhamo Khang, dedicated to Paldon Lhamo—a fierce protector deity—is located on the top floor with restricted entry; the eyes of the main icon are covered with a veil and only a high lama is allowed to open it on special occasions. The hall also houses several important manuscripts besides the Kangur and the Tangyur. The monks’ quarters line the slope densely, the space between the houses forming narrow alleys.

Fig. 2: Thiksey Monastery; view from the west side. Below: Thiksey Monastery; view of the south façade of dukhang, gonkhang and Rinpoche’s quarters. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

The main materials used for construction of all the buildings are stone—used mainly at the foundation or plinth level, cast mud bricks, wooden beams, purlins and wooden slats or willow sticks. The roof is laid out with compacted mud and clay.

In the last 15 years, many of the structures have been repaired with modern materials like cement. The monastery is listed as a structure of national importance by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Courtyard and Visitor Pavilions

A winding pathway leads up, through an elaborate gateway, to the courtyard around which are lined the main temples and other important structures (Fig. 3a). The courtyard is a very important ritual space for performing fire rituals and the festive dance (Cham). The space around the courtyard is organized to accommodate visitors attending the festival. On the south side of the courtyard is a covered pavilion with paintings on the wall (Fig. 3b). The central area is double the height of the pavilion and has an elaborate seating arrangement for the head of the order, who presides over the function. On the opposite side, below the red building, is a double-storied, elegant pavilion. The staircase leading to the dukhang and the roof of the pavilion are also used to seat visitors.

Dukhang

The largest structure on top of the hill, painted a yellow ochre, is the main prayer hall—the Dukhang (Fig. 4a). It is dedicated to the lineage gurus and the Rinpoche (the incarnate) whose quarters are located close by. The dukhang is accessed through a staircase leading to an entrance porch with paintings. The façade has wooden balconies two-stories high that accentuate the hall entrance. Twenty wooden pillars with decorated capitals are lined at the ground level, forming a gallery. On two high conical pedestals, each almost one-and-a-half metres high, are two sculptures of Shakyamuni. All the walls have relatively new paintings made to replace the original, damaged ones.

Behind the dukhang is a small antechamber called the tsangkhang, with a sculpture of Shakyamuni (Fig. 4b). Its antiquity is attested by the worn out stones paving the floor, the stone surface undulating with smooth curves, the shine almost matching a mirror. The walls have unique paintings with yaks and flayed skin. It seems that the function of this room has changed from being a space for esoteric practices to a gallery for visitors.

Fig. 4: General view of the dukhang. Below: General view of the Tsangkhang (antechamber of the dukhang) with sculptures of Guru Padmasambhava, Shakyamuni and Maitreya. The walls have esoteric paintings of animals and hanging, flayed skin. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

Gonkhang

The structure next to the dukhang, connected through walkways and a staircase, is one of the oldest structures in the complex . The red building of the protector deities is three storeys high above the courtyard. The first floor of this narrow building is in line with the dukhang entrance porch, access is through the staircase to the entrance porch. The small space with high roof is richly decorated with paintings. The gonkhang is a rectangular space, with large sculptures of fierce deities in stucco (Fig. 5 a & b). The walls in the gonkhang retain most of the original paintings and it is open to the public for a very short period during the year.

Fig. 5: Large stucco figures of fierce deities Mahakala and Dharmaraja. Below: Attendant figures for the fierce deities Mahakala and Dharmaraja. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

Chamba Lhakhang

Close to the gate leading to the courtyard on the left, a steep flight of stairs leads to the Chamba Lhakhang. This is one of the recent additions (1979–80) to the monastery, and houses the iconic two-storey high Chamba seated in the padmasana, the face of Ladakh tourism for a long time (Fig. 6 a & b). Around the shoulder level of the sculpture is a gallery for offering prayers and performing other rituals. The walls are painted extensively. In front of Chamba are windows through which his protective gaze falls over the village.

Fig. 6: Chamba (Maitreya), almost 40 feet high, in the cross-legged seated position by Nawang Tsering (1979 -80), stucco and paint. Right: Chamba (Maitreya) profile. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

Chorten

The Thiksey landscape is dotted with chortens (stupa) of all shapes and sizes (Fig. 7a). At the base of the hill is a mane wall behind which are a number of chortens. The monastery also has charge of many chortens in Shey and Nyarma.

Fig. 7: Kanika Chorten (above the access road—on the old path). Right: Ceiling of the Kanika chorten, with a mandala and four Avalokiteshwaras on the outside. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

Nyarma, one of the earliest sites in Ladakh believed to have been established by Rinchen Tsangpo, has ruins of an early temple and several stupas dating to the 11th century CE. One, in particular, has paintings inside (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8: View of the Nyarma Chorten; the entrance has been widened recently. Right: Paintings inside the chorten depicting various lineage gurus and deities of the Mahayana pantheon. Most of the images have been deliberately vandalized by scratching the face and eyes. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

IV. Paintings and Sculpture

Courtyard

The courtyard has been redone in the recent past. The paintings in the courtyard have been removed and repainted following the original scheme. Unfortunately, the present condition of the paintings is not good as poor quality pigments have been used and most have been affected by light.

At the centre of the courtyard, behind the Rinpoche’s seat, is Shakyamuni with his disciples. Flanked on either side is the Guru Padmasambhava and Tsonkhapa with fierce deities below. On either flank of the central double height structure, where Shakyamuni with his disciples and Guru Padmasambhava and Tssonkha pa are depicted, are the nine Arhats and two protector deities. Two panels, added later, depict the elephant, the monkey and the hare theme and the symbolic Prajnyaparmita on a lotus with a flaming sword emanating from it.

Chamba Lhakhang

The lhakhang is dedicated to Maitreya—the future Buddha. A 40-feet-tall sculpture of Chamba seated on the lotus throne, with hands in the Dharma Chakra Pravartana mudra (turning the wheel of Dharma), and a foliated crown on which the five Avalokiteshwara are depicted. The sculpture was consecrated in 1979–80, and executed by Nawang Tsering, a master sculptor in the traditional technique of stucco (Rigzin 1977: 118–19). There is fine detailing on the sculpture and an extensive use of gold and bright colours. The Maitreya is a masterpiece of contemporary Ladakhi art and is one of the most recognizable images from Ladakh, due to its extensive use in tourism. It has a beatific visage with compassionate eyes, the forehead has an urna (mark) made of a conch shell while precious and semi-precious stones have been used to adorn the crown and jewellery (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: Detail from the iconic Maitreya by Nawang Tsering. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

The walls surrounding the sculpture are full of paintings from the time of its consecration in 1979–80. The themes of these paintings are the Gelugpa lineage and the life of Buddha.

Dukhang

The entrance portico has paintings visibly of a later date (20th century), the main feature of these paintings is a limited colour palate (Fig. 10). Most of the colours are thickly applied and sensitive to light. Areas of painting exposed to direct sunlight are often faded. There is an overwhelming use of ultramarine blue, often it has not been properly mixed with the glue, thus, tending to dust off with touch.

Fig. 10: The guardian deities in the entrance porch of the main Dukhang. The images have been over painted in a crude manner with a limited palette, with an abundance of synthetic ultramarine. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

The iconographic programme[3] in the porch follows the tradition of four protector deities on either side of the entrance gate. The east wall has Mahakala holding the wheel of life and a tantric drawing on the other side is of a seated Shakyamuni. On the west wall is a Prjynaparamita on a lotus with the flaming sword. Above, in a row, are Maitreya, Avalokitesvara and Mahakala.

Describing the paintings in the dukhang, Snellgrove and Skorupski (1979: 115) write, ‘It contains along one side image Shakyamuni, Maitreya and so on, set against a wall which is elegantly painted, and all of which might have been done as late as the 19th century.’ However, a closer look at the paintings in the dukhang suggests several repair cycles, one at least as late as the 20th century. The original paintings dating to the foundation of the dukhang survive only partially.

South wall (Fig. 11)

Fig. 11: South wall of the dukhang with depictions of fierce deities of the Gelugpa lineages such as the six-armed blue Mahakala, a four-armed blue Mahakala and a Panjara Mahakala. (Digital composite, image by Sanjay Dhar)

The south wall has depictions of fierce deities of the Gelugpa lineage. On the left of the entrance door (facing the wall) is a Kavaca Heruka followed by a six-armed blue Mahakala along with a four-armed blue Mahakala and a Panjara Mahakala. Each of the principal deities is accompanied by minor fierce deities. The vibrant colours and excessive detailing of jewellery create a psychedelic effect.

On the other side is a Rakta Yamari, next to Paldon Lhamo on her horse wading through a river of blood. Nila Dharmaraja –Karmayama with a bull’s head and consort holding a blood filled skullcap is depicted along with Vaishravana and Kuber (Pita Jambhala).

East wall (Fig. 12)

Starting from the south corner is a depiction of Vajra Bhairava with his consort and Guhyasamaja (both important figures in the Gelugpa pantheon). Separated by a temporary supporting pillar, the theme is at a sharp contrast with that of the fierce deities. An 11-headed six-armed Avalokitesvara is depicted (this is from an earlier period and in a damaged state) and the centre of the wall has Shakyamuni flanked in three rows by the five Tathagata Buddhas.

On the same wall is perhaps the only surviving original painting depicting the Gelugpa lineage—Tsonkhapa and his two disciples with fierce deities. The layout and colouring of this section is reminiscent of the Narthang thangka series.

West wall (Fig. 13)

The west wall presents a damaged and dilapidated appearance, with some newly-painted sections. To the north are two mandalas: one is unfinished (seems to be in the process of being repainted) and the other is the mandala of the Guhyasamaja. Below them are two herukas (fierce deities). Next to it is Shakyamuni in the Dhyana mudra with eight Bodhisattvas. The portion beyond is newly painted with the in the theme of Shakyamuni with Tathagata. Next to it is an incomplete painting of Tara followed by yab-yam figures of Kalachakra, Chakrasamvara and Heruka.

North Wall (Fig. 4a)

On the north end of the dukhang is a wooden cabinet with sculptures of lineage gurus, Shakyamuni and thangka[S1] paintings and photographs.

Tsangkhang

On the north end of the dukhang is a small anti-chamber called the tsangkhang. It has large sculptures of Shakyamuni, Maitreya and Padmasambhava seated on the altar (Fig. 4b). The walls have paintings of tigers, bears, lions, vultures and yaks. Near the ceiling are depictions of flayed human and animal skin. Anatomically correct depictions of body parts hanging is also part of the display (Fig. 14 a & b). The painting style is quite unique being almost monochromatic; some of the drawings are similar to illustrations and Tibetan medical thangkas. However, the exact meaning and esoteric purpose of these paintings is not clear.

Gonkhang (Fig. 15)

Fig. 15: Figure with two faces being trampled by Dharmaraja (Detail); painted stucco, gonkhang. (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

The gonkhang is perhaps the only area that retains the painting and sculpture from the time of its consecration. It houses fierce deities and is open to public only for a limited period of time. Daily esoteric rituals continue to be performed here by senior monks, out of public view.

The gonkhang is accessed through an entrance portico with paintings of the protector deities on the south wall. The protectors are shown in a standing position, very different from the established iconography. There is a very strong element of Chinese art in these paintings, with all the four figures wearing shoes and holding their ayudhya (identifying object) almost in a military fashion as befits the protectors of the cardinal direction (Fig. 16).

The other two walls continue in the style from the tsangkhang, with elaborate drawings of symbols and animals. On the lower wall are common symbols like the dorje, ghanta, wheel, pasha, dammaru—all instruments for performing rituals. Above is an elephant, a wild yak and a vulture feeding on eyeballs. The south wall too has imagery of animals in flayed skins.

As one enters the gonkhang, the fierce visage of all the figures is intimidating. These are among the finest heruka sculpture in stucco, the scale and detail in execution is of the highest order. The sculptures are of Vajra-bhairava, Mahakala, Dharmaraja and Palden Lhamo along with several attendant figures (Fig. 5a & b). The walls also have paintings, now covered in soot, with similarities in technique to other sites of the same date (late 16th to 17th century) (Fig. 17b & c). The paintings are difficult to access behind the huge sculptures, with only the east side some visibility. The south wall has yaks and vultures with flayed skins repeated.

Fig. 17: Paintings of yaks, vultures and crows, on the south wall of the gonkhang. Bottom Left: Multiple figures in rows, with lineage deities above (not in the picture). It is difficult to access the paintings behind and on the sides of the sculpture. Bottom Right: A small detail from the east wall (digitally manipulated). (Image by Sanjay Dhar)

Kanika Chorten

The chorten on the pathway above the present access road has been restored but the interior paintings (done on cloth and pasted on wood) on the ceiling (Fig. 7b & c) and drum are of an earlier date (18th century). The centre has a mandala while on the sides are four Bodhisattvas.

Nyarma

Nyarma is an ancient site dating to the 10th–11th century and has an early chorten with very fine early period paintings depicting lineage gurus and other minor deities. These paintings have been damaged in acts of vandalism/iconoclasm by the Dogra soldiers (as per local belief). The paintings inside the chorten were not intended for viewing, but as an offering. Traditionally, when chortens are made, tsa tsa (clay tablets embossed with mantras or images, gold and silver) are buried deep inside the core.

The paintings are ‘hurried’, the technique is basic with a base coat of white and limited palette. However, the iconographic scheme and details of mudras, ayudha and other defining features have not been compromised. The brushwork, particularly in the use of black for the line work, is bold and confident. This elevates the quality of the painting, giving it a unique character (Fig. 8b & C).

V. Thiksey Festival

Every year, in the 12th month of the Tibetan calendar, a three-day festival is held at Thiksey, popularly called the Thiksey Gutor (Khrig-rtse dGu-gtor). On this occasion, followers make offerings of the sacrificial cake and Cham (masked dance) is performed in the courtyard. The characters for most of the dances are from the Gelugpa pantheon, with Dharmaraja and his spouse alongside two guardian deities being among the most important ones. Animal masks (yak and deer) also make an appearance along with the lion-headed goddess. The dance is performed by a large number of characters such as nagas, yakshas, rakshasas, etc., and ends with the demon-shaped cake being sacrificed by dancers in black hats.

The main festival is followed by several smaller ones during the winter months, when a large number of locals visit the monastery. (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1979: 115)

Notes

[1] Photang is a meeting of senior lamas to discuss various issues related to the order and also to consider what is required to go forward. The event is also primarily meant for considering religious/ritual and related issues. On the occasion, believers also receive sermons and teachings from various high lamas.

The trend of holding an annual photang was started by the Drukchen (head of the Drukpa Kagyupa sect). In Ladakh, other denominations have also started holding an annual photang for which a dedicated space is allocated.

[2] Near Shey is a large area populated with chortens of all shapes and sizes, most dating to an early period from the 12th century onwards.

[3] Identification of various deities is primarily corroborated by Lokesh Chandra (2006).

References

Chandra, Lokesh. 2006. Buddhist Iconography. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

Dainelli, Giotto. 1933. Buddhists and Glaciers of Western Tibet. Translated by Angus Davidson. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh: 950–1842. Rome: L'Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

Rigzin, Tsewang. 1997. ‘Religious Bodhi Literature in Ladakh’. In Recent Researches on the Himalaya, edited by Prem Singh Jina, 117–121. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Snellgrove, David L. and Tadeusz Skorupski. 1979. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Bibliography

Francke, A.H. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Edited by F.W. Thomas. New Delhi: Low Price Publication, 1999.

Gordon, Antoniette K. The Iconography of Tibetan Lamaism. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 1998.

Gyaltsen, Jamyang. ‘Hemis Tsechu of Ladakh’. In Development of Ladakh Himalaya: Recent Researches, translated by Prem Singh Jina, 65–68. New Delhi: Gyan Books, 2002.

Khosla, Romi. Buddhist Monasteries in the Western Himalayas. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1979.

Other sources

HAR/ Himalayan Art Resources: http://www.himalayanart.org/

Primidi: http://www.primidi.com/thikse_monastery/history