Fig. 1. Women members of the family engaged in the colour-filling activity

Photographs by Neha Thakar

Introduction

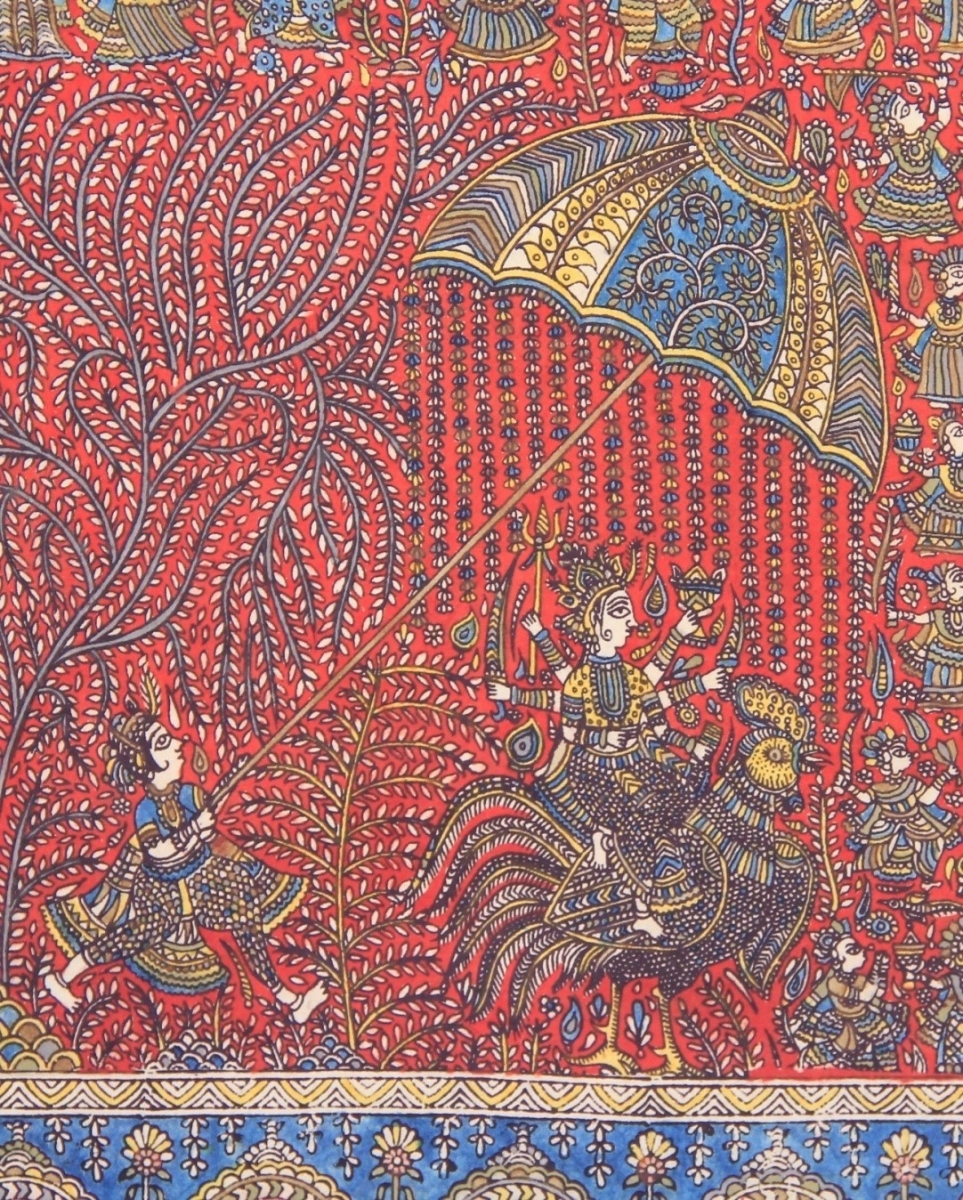

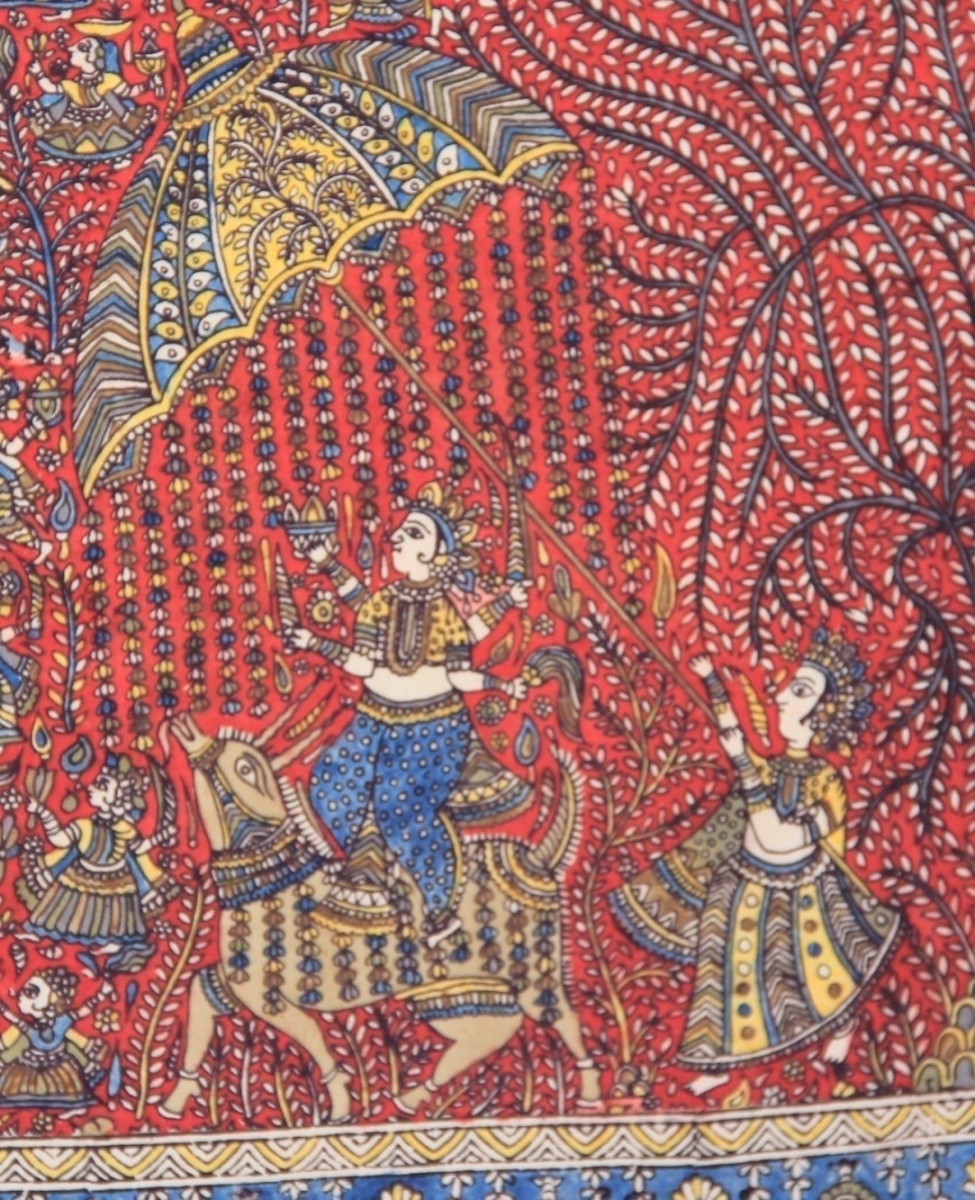

Gujarat has a very rich textile tradition. Kalamkari work, in the form of Mata ni Pachhedi (backdrop of the mother goddess) and Mata no Chandarvo (canopy of the mother goddess), is a unique textile-painting and block-printing tradition of Ahmedabad, practised by a handful of Vaghari community chitaras (painters). Mata ni Pachhedi usually depicts mother goddesses as mataji, mostly with the use of black, maroon and indigo colour with hand- painted or block-printed decorative borders called lassa patti. The Vagharis also call themselves as Devipujak and they accept commissions of paintings from all Devipujak communities to fulfil ritual requirements during Navaratri. Pachhedi is also used as a chandarvo (canopy) to form a temporary shrine as religious rituals are involved.

The Vaghri Community

Vaghris of Gujarat are landless labourers, working as stone-masons, or selling cattle, goats, vegetables and datan-twig toothbrushes for their living. This community is devipujak and their main deities are Meldi Mata, Kalika Mata, Khodiyar Maa, Bahucharaji/Becharaji etc. The Vaghris also believe in animal sacrifice to Mataji for various pujas where consumption of meat and alcohol seems to be a culturally accepted custom.

There is an interesting legend about how this art of textile painting/printing reached the Vaghri community. About 300 years back the Chhipa ('one who prints') community used to paint images of goddesses and other decorative motifs on textile with kalams (bamboo/wooden sticks or twigs) and also developed carved wooden blocks to print such images for quicker representation. These were the people who spread this art in the religious and cultural life of Gujaratis. Once, during a period of economic deficiency, Chhipas sold their wooden blocks to a Vaghri trader of Viramgam. This Vaghri family themselves started textile printing with the help of those blocks and developed this unique style of textile painting and printing. Afterwards Vaghris migrated to Ahmedabad to expand their business (Jadhav 1975).

Fig. 2. Khodiyar mata seated on her vahana, the crocodile, in the shrine

Religious and ritualistic concerns

The Devi cult is widely popular in Gujarati culture, where the beliefs and practices of non-literate villagers and oral traditions of myth are more important than that which is recorded in classical Sanskrit literature composed by Brahmins. Every village has its own mother goddesses, depicted without her consort seated on different vahanas (vehicles). It is observed that they represent mother goddesses generally without her consort so that they can function independently without censure in the absence of marital control. Such worship of village goddesses minimises the hierarchy between Mataji and devotee (Gatwood 1985). The iconography specifically developed to depict particular goddesses serves as an important visual language to identify them. Pachhedis of Mataji are produced as display and offering to the shrines of mother goddesses, generally by the Vaghri community who consider themselves devipujak (worshippers of mother goddesses). Initially, this nomadic community used to erect temporary shrines by stretching backdrops behind the image of Mataji and use canopies serving as ceilings of nomadic shrines. Such backdrops and canopies are used by devotees during Navaratris of March and October, and also the 10 days' Dashama vrat celebration during July-August.

Local Mother Goddesses and their Vahanas (vehicles)

Khodiyar mata (crocodile)

Bahuchara/Becharaji mata (cock)

Vahanvati mata (ship)

Meladi mata (goat)

Dashama (camel)

Many times such textiles are donated by devotees after the fulfilment of wishes. These goddesses keep members of the devotee's family healthy. They control the rains and weather, cure animal diseases and guard the region against natural as well as supernatural calamities (Gatwood 1985).

Fig. 3. Visat mata on her vahana (the buffalo)

Fig. 4. Bahuchara mata on her vahana (the cock)

Fig. 5. Meladi mata on her vahana (the goat)

Materials and Methods

The format of traditional pachhedis and chandarvo is a rectangular fabric divided into seven to nine compartments that contain human figures of the purvaj (ancestors), Devi worshippers or other narrative themes with the mother goddess seated on her vahana in the centre without her consort. This format may different depending on artists’ creativity, personal imagination or the client’s demand.

Fig. 6. Fulni malan (women with garlands of flowers), animals and other motifs.

Fig. 7. Purvaj (ancestor) on horse and other motifs

Artists use de-starched cotton fabric and wash it in water mixed with harde powder to prepare it for holding colours. One of the artists, Sureshbhai Chitara of the Vaghri community, enthusiastically demonstrated the process of Pachhedi painting, making of natural colours, usage of chemical dyes, methods of painting with twigs and wooden-block printing. He and his father Sanatbhai also demonstrated the technique of washing cloths after painting/printing to prepare permanent coloured textiles out of raw dyed cloth. Female members of their family also participate in the process of making pachhedis and hangings.

Figs. 8–11. Natural maroon dye; Black colour prepared for block print; Drawing with a twig; Wooden blocks for printing

Drawing is an essential part in pachhedi making before colour filling. Artists usually use twigs of the babul tree as kalam and either draw bold black outlines or use blocks to print images of goddesses, other human figures, animals etc. The black colour is prepared by the oxide of iron mixed with jaggery. Red colour is made of extract of tamarind seeds. Traditional pachhedis are generally painted in very limited colours such as black, red/maroon and indigo; some areas are supposed to be left blank i.e., white. After finishing drawing, painting and printing the fabric is boiled in alizarian solution mixed with flowers of dhavadi (a local plant that leaves a yellowish colour after mixing with boiled water) to bring out the brightness of colours, and then washed in the running water of the Sabarmati river. This lengthy process of fully preparing a piece of textile takes three to four days of patience.

Fig. 12. Sanatbhai and Sureshbhai demonstrating the washing process. Fabric is washed in boiled water mixed with alizarin solution and dhavadi leaves.

Fig. 13. Block-printing demonstration.

From ritual paintings to popular consumable products

According to Sureshbhai Chitara, his generation of artists learned many methods of making natural colours out of flowers, stones and vegetable dyes from his forefathers. Nowadays artists have incorporated many more colours such as sap green, yellow ochre, indigo in the painting and sometimes avoid traditional methods of extracting colours from natural materials, as fabric colours are easily available at lower cost to meet the demand of their clients especially during the Navaratri festival. Artists also divert their skills to fascinate visitors, by designing small souvenirs, stoles, odhni/dupattas, bed sheets, pillowcases and wall hangings that incorporate new motifs in the traditional style of representation. Sometimes Mataji’s images are avoided to retain the sanctity of the religious usage of pachhedis/chandarvo.

Fig. 14. Pachhedi with Visat Mata in centre, painted in fabric colours

Fig. 15. Khodiyar mata pachhedi painted in natural dyes

Fig. 16. Meladi as Vahanvati Mata seated on her vahana in the ship

To popularise this art, artists are also engaged in teaching this art by conducting workshops at their homes. Some of them are also invited to give demonstrations at schools and colleges (of design and fine arts). With the help of these artists, designers have started to incorporate their skills in product design and fashion accessories.

Fig. 17. Visat Mata (centre), Bahuchar Mata (left), Meladi Mata (right)

Artists: Profiles and their expectations

In a city like Ahmedabad, these artists reside in houses with one or maximum two rooms, in very small basti-streets of the Vasana area, and work in the streets or roadside footpaths. During the rainy season they used to work under self-constructed shades. Further this lengthy process demands adequate space to wash and dry the cloth, prepare colours, to spread out the cloth for colouring and printing with blocks etc. The artists are willing to overcome this working-space problem, and also to link themselves with government or non-governmental organisations, who can contribute to the expansion of their practice and trade in a systematic way, by inviting them for demonstrations, workshops and exhibitions in different regions.

Profiles

Sanatbhai Chitara

Date of birth: June 10, 1947

Practising this art for 50 years

National Merit Award from the Ministry of Textiles in 2005

Gujarat State Award from Ministry of Culture, 2012

Sureshbhai Chitara

Date of birth: September 4, 1985

Practising this art for 20 years

Gujarat State Award in 2007

Rajeshbhai Chitara

Date of birth: April 19, 1973

Practising this art for 30 years

Dineshbhai Chitara

Date of birth: June 16, 1974

Practising this art for 27 years

Vijaybhai Chitara

Date of birth: November 24, 1978

Practising this art for 25 years

Gujarat State Award in 2007

Chandrakantbhai Chitara

Practising this art for 32 years

Gujarat State Award in 2001, National Award in 2003

Merit Awards in 1997 and 2001.

Shyambhai Bhikhabhai Chunara

Practising this art for 22 years

Female artists of Sanatbhai Chitara's family

Jashiben Sanatbhai Chitara

Practising for 35 years

Anitaben Dineshbhai Chitara

Practising for 15 years

Ramilaben Rajeshbhai Chitara

Date of birth: February 5, 1981

Practising for 19 years

Hetalben Sureshbhai Chitara

Date of birth: September 29, 1991

Practising for 7 years

Note: This article is based on conversations with Pachhedi artists; only a few works were consulted for the sections on the Vaghri community and religious and ritualistic concerns.

References

Hawley, John Stratton and Donna Marie Wulff, eds. 1995. The Divine Consort-Radha and the Goddesses of India. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.

Jadhav, Joravarsinh. 1975. Lokjeevan-na moti [Gujarati]. Ahmedabad: Gujarat Rajya Lok-sahitya Samiti.

Lynn Gatwood Lynn. 1985. Devi and The Spouse Goddess: Women, Sexuality, and Marriage in India. New Delhi: Manohar Publications.