Lucknow, a city of monumental cultural legacy, owes much of its vibrant heritage to the Nawabs of Awadh or Oudh. While the Mughals laid its foundations, the Nawabs elevated Lucknow to unmatched grandeur. The Nawabi era began in 1722 with Saadat Khan, who established Awadh as a semi-autonomous province under the Mughal Empire. Over time, his successors shaped Lucknow’s unique identity, with a few standing out for their exceptional contributions. In 1811, Ghazi-ud-Din Haider declared independence and assumed the title of king, yet the term ‘Nawab’, derived from the Arabic naib (deputy), remained synonymous with Awadh’s rulers.

Painting depicting the Nawabs of Awadh, 1858-69. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

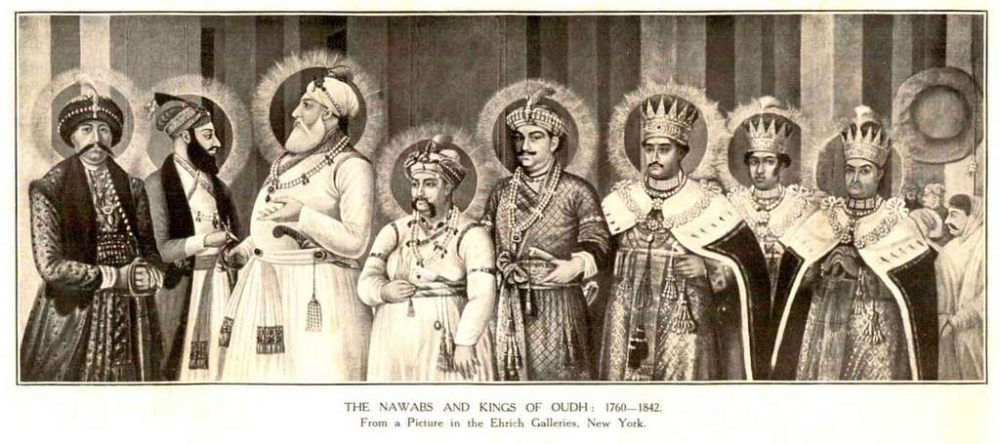

The Nawabs of Oudh/Awadh, 1760-1842, published in Bengal: Past and Present, Vol-43, 1932. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

Posthumous portrait of Nawab Saadat Khan I of Awadh (r.1722-39), 1760. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Nawab Ghazi ud-Din Haidar (r. 1814–27) entertains Lord and Lady Moira to a banquet in his palace, Opaque Watercolour, 1820–22. (Picture Credits: British Library/Wikimedia Commons)

The Nawab Who Built to Feed

Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula (1748–97), the fourth Nawab of Awadh, is remembered as the visionary who transformed Lucknow into a city of architectural magnificence while earning the love of his people through acts of generosity. His rule marked a golden era, where grandeur and humanity coexisted harmoniously.

During the devastating famine of 1784, Asaf-ud-Daula initiated the construction of the Bara Imambara, a project that transcended mere charity. Rather than dispensing aid, he provided dignified employment to thousands, from common laborers to noblemen. This initiative, marked by its ingenuity and compassion, solidified his reputation. Beyond his humanitarian intentions, Asaf-ud-Daula’s role as a patron of architectural splendour is evident in the massive vaulted hall and the enigmatic Bhool Bhulaiyaa (maze) of the Bara Imambara.

Portrait of Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab of Awadh (r. 1775–1797), 1780. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Bara Imambara known for its massive vaulted hall and the enigmatic Bhool Bhulaiya. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

The Bhool Bhulaiya, a labyrinth of interconnected passages, designed above the Imambara hall. Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Under Asaf-ud-Daula’s patronage, Lucknow blossomed into a cultural epicentre. He attracted poets, musicians and artists from across the subcontinent, especially those migrating from Delhi due to political upheavals. This migration led to the establishment of the Dabistan-e-Lucknow, a distinct school of Urdu poetry characterised by its unique style and themes. The Nawab’s court was graced by eminent poets such as Mir Taqi Mir, who, despite initial reservations about Lucknow’s poetic style, contributed significantly to its literary scene. Asaf-ud-Daula himself dabbled in poetry, earning recognition for his compositions.

The Poet-King of Elegance

The last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah (1822–87), was an enigmatic figure whose reign, though marred by political turmoil, is remembered for its profound cultural and artistic contributions. While history often judges him for the annexation of Awadh by the British in 1856, his true legacy lies in his artistic soul.

Wajid Ali Shah was both a patron and practitioner of the arts. Trained in music by Tansen’s descendants and in Kathak by Thakur Prasadji and Bindadin Maharaj, he infused the dance form with theatrical elements, shaping the Lucknow gharana. His Raas Leela performances reflected his devotion to Krishna, while his influence on thumri music endures. Writing as ‘Qaisar’ and ‘Akhtarpiya’, he composed poetry and songs, including the iconic composition ‘Babul Mora Naihar Chhooto Hi Jaye’. His extensive literary works, including Ishqnama, offer deep insights into nineteenth-century Lucknow’s cultural landscape.

An engraved portrait of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1847-1856), 1872. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Students learning kathak. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

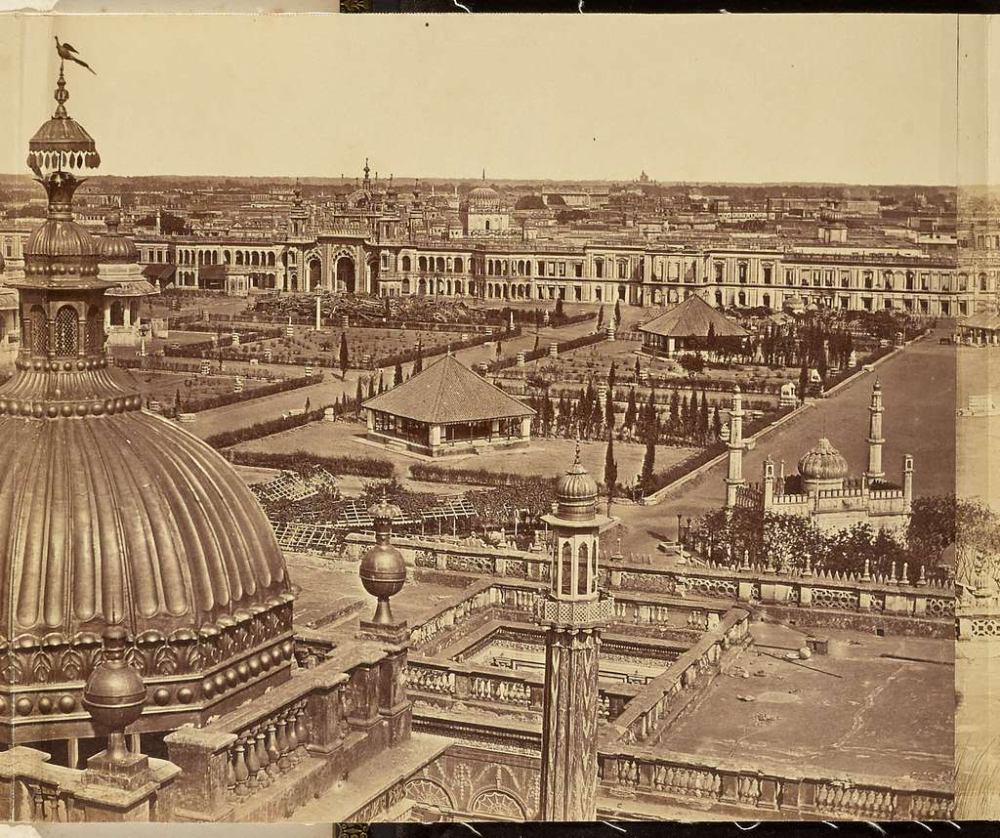

Qaiserbagh complex captured by Felice Beato after the destruction during the siege of Lucknow, 1858. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

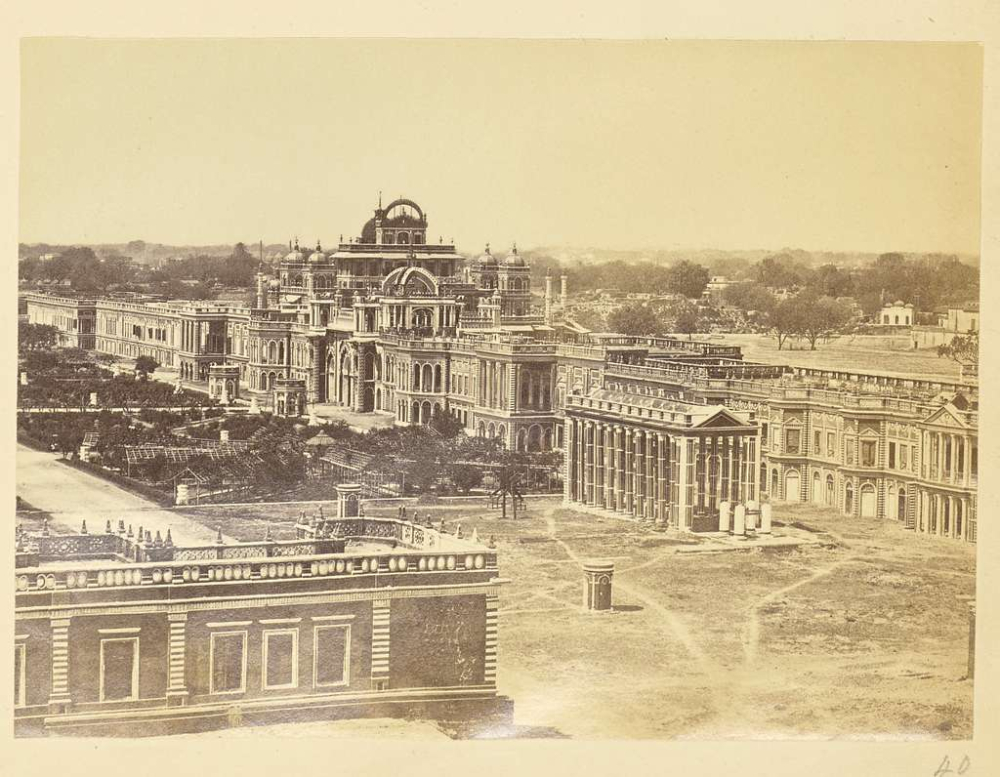

View of Qaiser Pasand Palace in the Qaisarbagh complex, 1863-1887. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

The Nawab’s aesthetic sensibilities extended to architecture as well. Designed to emulate paradise on earth, the Qaiserbagh Palace complex featured fountains, gardens and the famed Parikhana (Palace of Fairies), which housed his consorts and female performers. Despite its partial destruction after the Revolt of 1857, it remains a testament to his aesthetic sensibilities.

Recent scholarly research challenges the anecdote suggesting that Wajid Ali Shah refused to leave his palace due to the absence of his shoe servant when the British arrived to depose him. This narrative, often cited to depict the Nawab’s indulgence in ceremony, lacks historical evidence and appears to be a colonial construct aimed at undermining his reputation. Instead, he chose non-violent resistance, departing willingly to negotiate with the British. His exile in 1856 deeply affected the people of Awadh, sparking widespread mourning. For days, the streets of Lucknow resonated with cries of grief, and poets penned poignant lamentations in his memory. In Matia Burj, near Calcutta, he recreated a ‘mini-Lucknow’,’ preserving Awadhi culture through Kathak performances, poetic gatherings and architectural endeavours.

A Glimpse of Nawabi Splendour

The legacies of Asaf-ud-Daula and Wajid Ali Shah offer us a window into the opulent lifestyle of the Nawabs, where beauty and grandeur were integral to daily life. Imagine, during Wajid Ali Shah’s reign, strolling through Lucknow’s lanes at dusk—the air infused with rose water, ittar-lit lamps casting a golden glow—a vision of royal procession for every citizen. Even the most ordinary objects bore the imprint of refinement—fly whisks inlaid with rubies, carpets woven with threads of gold and garments embroidered with real silver.

The Nawabs’ penchant for extravagance extended to their royal kitchens, where culinary artistry reached unprecedented heights. Wajid Ali Shah’s chefs perfected the dum-pukht technique, which involved slow-cooking dishes within sealed pots to lock in flavours. The result? Fragrant biryanis enriched with Persian saffron and garnished with edible gold and silver foils. Legend has it that these delicacies were so exquisite they could stir emotions with a single bite.

Then there were the grand processions. On auspicious occasions, Wajid Ali Shah would ride through Lucknow, seated regally atop an elephant adorned with a gold-plated howdah. The elephant itself would be draped in fabrics embroidered with shimmering zari threads. As the Nawab passed, the crowds would marvel at this moving spectacle of opulence, an embodiment of Lucknow’s grandeur.

But perhaps the most romantic tale of excess comes from a moonlit garden in Qaiserbagh. On one magical night, Wajid Ali Shah, intoxicated by the beauty of his surroundings, ordered pearls to be scattered across the lawns. The silver glow of the moon kissed each pearl, turning the garden into a celestial dreamscape.

Yet, this indulgence in grandeur was not mere extravagance; it was an assertion of cultural identity. In an era of colonial encroachment, the Nawabs’ patronage of art, poetry and music became an act of preservation, a means of inscribing Awadhi heritage into the collective memory of its people.

The Begums

Bahu Begum (1727–1815), the wife of Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula, was one of the most powerful women in Awadh’s history. After her husband’s death, she amassed immense wealth, controlled vast jagirs, and exercised significant influence in court politics, particularly during the succession struggle between Asaf-ud-Daula and his brother, Mirza Jawwad. Her residence in Faizabad, the opulent Chhoti Kothi, became a hub of power, where she skilfully negotiated with British officials to maintain her authority. Even the British, who sought to weaken Awadh, acknowledged her financial and political acumen, referring to her as ‘the wealthiest woman of her time’. She commissioned the grand Bahu Begum ka Maqbara in Faizabad, where she was eventually laid to rest, an architectural marvel that remains one of Faizabad’s finest structures.

Tomb of Bahu Begum in Faizabad. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Tomb of Begum Hazrat Mahal in Kathmandu, Nepal. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Another influential royal woman was Begum Hazrat Mahal, the courageous wife of Wajid Ali Shah, who became a central figure in the 1857 Revolt. After her husband’s forced exile to Calcutta, she refused to surrender and instead led the rebellion against British forces, rallying troops and forming crucial alliances with zamindars and local chieftains. She even declared her son, Birjis Qadr, the ruler of Awadh, challenging colonial authority in a bold assertion of indigenous sovereignty. Later, forced into exile, she was buried in Kathmandu.

Apart from their political roles, the Nawabi begums were great patrons of art, architecture and charitable institutions. Malka Jahan, the mother of Amjad Ali Shah, was instrumental in the beautification of Lucknow, funding the construction of the Malka Jahan Mosque and several gardens that adorn the city. She was buried in the Shah Najaf Imambara, a site of deep religious significance. Similarly, Qudsia Begum, another influential queen, contributed to the architectural legacy of Lucknow by commissioning public works that enhanced the city’s cultural appeal.

These women were not mere consorts; they were administrators, warriors, patrons and custodians of Awadhi heritage. Their architectural commissions, political manoeuvres and acts of resistance ensured that their legacies endured alongside those of the Nawabs, shaping the history of Awadh in ways that continue to be remembered today.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).