The story of Lucknow is equally rooted in myth and legends as it is shaped by centuries of political shifts and cultural evolution. Nestled on the banks of the Gomti River, the city’s origins, and its name, is often linked with the epic Ramayana, where it is recorded to have been founded by Lakshmana, the devoted brother of Rama, and named Lakshmanapuri. Over time, this name evolved into Lakhanpur, Lachhmanpur and, finally, Lucknow.

Chattar Manzil from the Gomti River, 1895. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

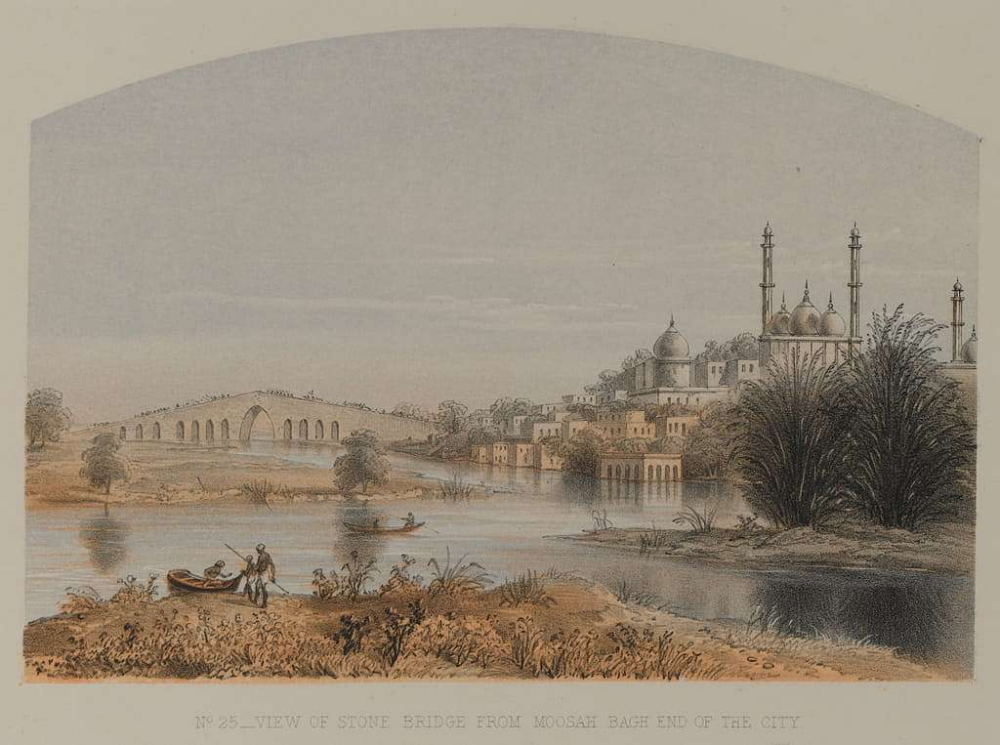

The Gomti River, looking towards the Stone Bridge. From drawings made on the spot by Lieut. Col. D. S. Dodgson, A.A.C. London: Day & Son, Gate Street, Lincoln's Inns Fields. (Picture Credits: British Library/Wikimedia Commons)

Gomti River. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Early Settlements

Historically, Lucknow was part of the larger Kosala region, one of the 16 famed mahajanapadas (sixth century BCE) known for its spiritual and intellectual pursuits. The city’s location along the fertile plains of the Gomti not only sustained agriculture but also facilitated trade, enabling continuous human settlement. Archaeological excavations at the Hulaskhera mound, near Karela Lake in Mohanlalganj tehsil, reveal traces of habitation from c. 1000 BCE to the Sunga-Kushan period (second–third century CE), with discoveries of terracotta figurines, shell beads and structured dwellings pointing to a thriving society at that time.

Early Vedic texts, including the Shatapatha Brahmana, describe settlements within Kosala, while Buddhist scriptures such as the Anguttara Nikaya and the Jataka Tales mention nearby Shravasti, reinforcing Lucknow’s significance within the region’s ancient urban network. Greek ambassador Megasthenes described fortified cities in the region, aligning with the excavated brick fort at Hulaskhera, which may have served as an administrative centre. During the Mauryan period (c. 321–185 BCE), Kosala was absorbed into Ashoka’s empire, and later, under the Kushan rulers, it flourished as an economic and religious hub, with trade links extending to Central Asia. Archaeological evidence, such as Kushan-era silver coins, gold-coated glass beads and a Kartikeya gold plaque—now housed in the Mathura Museum—suggest active external trade and religious diversity. Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang also documented Kosala’s monasteries and urban centres, affirming the region’s continued prominence in early medieval India.

During Medieval Times

While human settlement in the region is well documented, Lucknow’s recorded history emerges in the fourteenth century, when it became part of the Delhi Sultanate. Sultan Iltutmish granted the aqta (land assignment) of Kasmandi and Mandiaon to Malik Tajuddin Sanja, also known as Tabar Khan, integrating Lucknow into the Sultanate’s administration. The first written reference to a name resembling ‘Lucknow’ appears as ‘Alakhnau’, recorded alongside Awadh and Zafrabad, during Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s reign (1325–51 CE). The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, visiting the region between 1338–141, noted the region’s agricultural wealth, particularly its role in supplying grain to Delhi during a severe famine. This prosperity led the Governor Ainul Mulk to rebel, though Muhammad bin Tughlaq eventually suppressed this rebellion with great difficulty.

By 1394, Lucknow came under the influence of Khwaja-e-Jahan, the founder of Sharqi dynasty of Jaunpur, before Sultan Bahlul Lodi (r. 1451–89) annexed it and assigned it to his grandson Azam Humayun. During this period, Lucknow’s landscape reflected a cultural blend that would go on to define its character for centuries. Mohsin Kakorvi’s verse metaphorically captures this confluence:

Simt-e-Kaashi Se Chala Jaanib-e-Mathura Baadal

Barq Ke Kaandhay Pe Laayi Hai Saba Ganga-Jal

(From Kashi to Mathura, the clouds move,

The breeze carries Ganga water on lightning’s shoulders.)

With Babur’s victory at Panipat (1526), Lucknow came under Mughal rule. Though Babur’s son Humayun briefly lost control to Afghan rebels, he reclaimed his territories in 1528. The Baburnama describes Humayun’s crossing of the Gomti en route to Faizabad, noting the region’s pleasant climate and flavourful rice. Following Humayun’s defeat, under Sher Shah Suri (r. 1539–45), the region’s governance was entrusted to Isa Khan and Qadir Shah, who established a silver and copper mint, elevating Lucknow’s economic standing.

Built around 1620 CE, Nadan Mahal is a Mughal-era site housing the tomb of Sufi saint Shaikh Abdul Rahim. (Picture Credits: Stuti Mishra)

Farangi Mahal. (Picture Credits: Stuti Mishra)

During Akbar’s reign (1556–1605), Lucknow became a vital administrative centre, the headquarters of a sarkar in the suba of Awadh. The earliest known Mughal governor of Lucknow was Husain Khan, followed by Jawahar Khan, who served as subedar of Awadh. His deputy, Qasim Mahmud of Bilgram, played a key role in developing Shahgunj, Mahmud Nagar and Akbari Darwaza, the latter still standing in Chowk today. Abdur Rahim Bijnori, a prominent noble at Akbar’s court, was entrusted with constructing Machchhi Bhavan and Panch Mahal in Lucknow. His tomb at Nadan Mahal, one of the oldest surviving Mughal-style monuments in the city, stands as a testament to early Mughal architectural grandeur. Abul Fazl’s Akbarnama also highlights Lucknow’s increasing prominence due to its favourable climate and fertile lands, making it a key part of the Awadh suba.

Subsequently, Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), who had previously visited Lucknow during Akbar’s reign, expanded the city by establishing Mirza Mandi west of Machchhi Bhavan. The accounts of European traveller De-Laet dating to this period describe Lucknow as a thriving trade hub, referring to it as a ‘Magnum Emporium’. About the same time, a French merchant secured a one-year trading permit in Lucknow, amassing great wealth. When the permit expired, his confiscated mansion was renamed Farangi Mahal, which, under Aurangzeb’s rule, was transformed into a renowned centre of Islamic learning under the patronage of Mulla Qutubuddin’s family.

Under Shah Jahan (r. 1627–58), Awadh’s governorship was entrusted to Sultan Ali Shah Quli Khan, whose sons established Fazil Nagar and Mansur Nagar near Akbari Darwaza, further contributing to the city’s urban expansion.

The Arrival of Nawabs

As Mughal authority waned, the Nawabs of Awadh rose to prominence. In 1722, Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-Mulk was appointed as the first Nawab of Awadh, establishing an autonomous dynasty. His successors, Safdar Jang and Shuja-ud-Daula, consolidated Awadh’s independence, with the latter playing a decisive role in the Battle of Buxar (1764). However, his defeat at the hands of the British East India Company led to the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), making Awadh a British buffer state.

Posthumous portrait of Nawab Saadat Khan I of Awadh (r.1722-39), 1760. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Nawab Safdar Jang (r. 1739–1754), early 18th-century Mughal portrait. (Picture Credits: Smithsonian Freer Sackler Gallery/Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula (r. 1754–1775), 18th-century painting by Tilly Kettle, a British who was active in India from 1769 to 1776. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab of Awadh (r. 1775–1797), 1780. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Nawab Saadat Ali Khan II (c. 1752–1814) by George Place, 1799. (Picture Credits: Royalcollections.org/Wikimedia Commons)

An engraved portrait of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1847-1856), 1872. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

It was Asaf-ud-Daula (r. 1775–97) who truly reshaped Lucknow’s destiny, shifting the capital from Faizabad to Lucknow in 1775. Under his rule, the city witnessed an architectural and cultural renaissance, which saw the construction of Bara Imambara, Rumi Darwaza and Asafi Mosque. His legendary generosity, particularly during the famine of 1784, earned him the saying: ‘Jisko na de Maula, usko de Asaf-ud-Daula.’

A colonial-era print of Rumi Darwaza and the gateway of Bara Imambara. (Picture Credits: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One of the most fascinating aspects of this era was the city’s vibrant social life. Mir Taqi Mir, the legendary poet, wrote of the grandeur of Lucknow’s courtyards, while European travellers marvelled at its bustling bazaars, where silk merchants, calligraphers and perfumers thrived. The kothas (courtesan houses) were not just centres of entertainment but also hubs of refined poetry, dance and etiquette, from where luminaries like Begum Akhtar would later rise to fame.

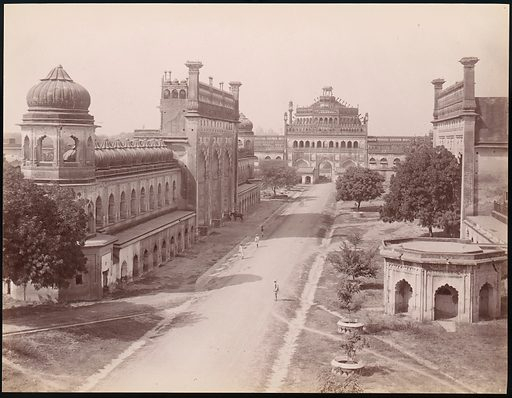

British Control and the Revolt of 1857

In 1798, the British installed Saadat Ali Khan II (r. 1798–1814) on the throne of Awadh, ensuring a ruler aligned with their interests. His reign saw the construction of Dilkusha Kothi, Hayat Baksh Kothi, Farhat Baksh Kothi and Chattar Manzil. By the early nineteenth century, British influence deepened—Warren Hastings had stationed a Resident in Lucknow as early as 1773, and by the reign of Ghazi-ud-Din Haider (r. 1814–27), Awadh had become a nominally independent kingdom under British dominance. Despite this control, Nawabs like Ghazi-ud-Din Haider, Nasir-ud-Din Haider (r. 1827–37) and Muhammad Ali Shah (r. 1837–42) continued Lucknow’s artistic and architectural patronage, commissioning landmarks like Shah Najaf Imambara, the Tomb of Saadat Ali Khan, Tarbiyat Kothi, Hussainabad Darwaza, Chhota Imambara, Satkhanda and Husainabad Clock Tower.

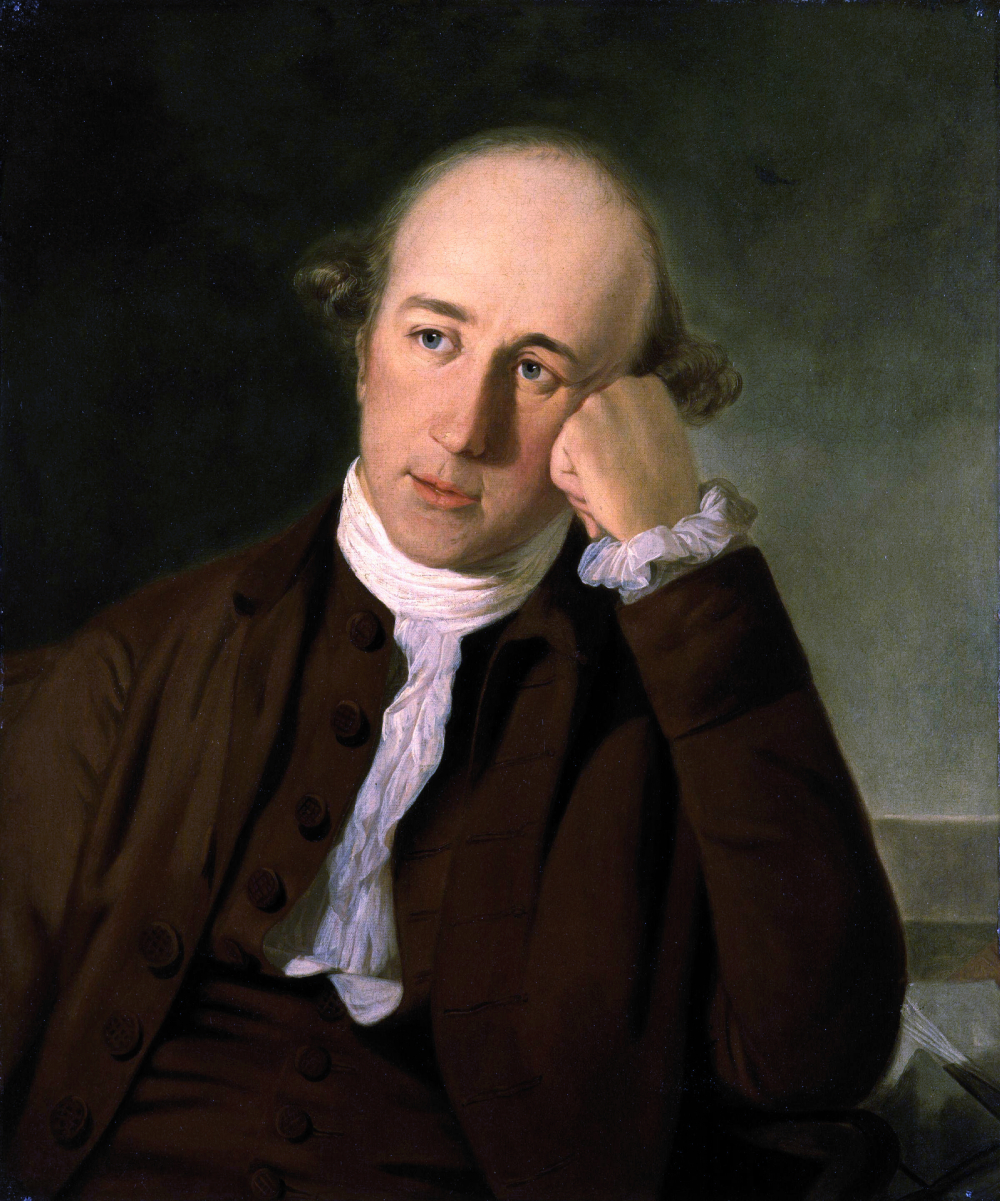

Portrait of Warren Hastings (1732–1818) by Tilly Kettle, 1772. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Walls of the Residency complex still marked by cannon fire from the siege of 1857. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

In 1847, Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1847–56), the last Nawab, ascended the throne. More inclined towards the arts than politics, his reign saw the construction of Qaiserbagh palace complex, a symbol of Lucknow’s opulence. However, British dissatisfaction with Awadh’s administration gave Lord Dalhousie the pretext to annex the kingdom in 1856, citing ‘misgovernance’. Wajid Ali Shah was exiled to Matia Burj near Kolkata.

In 1857, Lucknow became a major battleground during the First War of Independence. Begum Hazrat Mahal led the rebels in a valiant attempt to reclaim the city. The Siege of the Residency (July–November 1857) saw British forces besieged for 87 days before reinforcements arrived. Despite fierce resistance, the British recaptured Lucknow in 1858, forcing Begum Hazrat Mahal to flee to Nepal, where she continued her resistance in exile.

Colonial Retaliation and Cultural Resilience

After crushing the Revolt of 1857, the British demolished several Nawabi estates, replacing them with colonial structures to establish dominance. Buildings like St. Joseph’s Cathedral (1860s), Christ Church (1860s), Butler Palace (1920), GPO (1929) and the Vidhan Sabha (1922–28) were constructed, while structures such as La Martiniere College and Chattar Manzil were repurposed for British use. Despite this, Lucknow remained a hub of cultural excellence, preserving its Urdu poetry traditions, including marsia (mourning poetry), rekhti (women’s poetry) and ghazal.

Lucknow in the Freedom Movement

In the early twentieth century, Lucknow played a crucial role in India’s freedom struggle. The Lucknow Pact (1916) marked a historic moment of Hindu-Muslim unity, while leaders like Abul Kalam Azad and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai emerged as key figures in the movement. During the Quit India Movement (1942), the city became a centre of protests, with students and activists leading demonstrations against British rule. By 1947, as India gained independence, Lucknow emerged transformed—its legacy of resistance deeply intertwined with its rich cultural heritage.