Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, boasts a rich architectural tapestry woven from indigenous building traditions and external influences. The city's historical landscape, dominated by Mughal gardens, dhajji dewari (traditional Kashmiri houses) and religious structures evolved significantly with the advent of modern architectural practices, subtly altering the urban fabric. While Srinagar’s historical vernacular structures have always attracted admiration, its modern architectural heritage remains an often-overlooked treasure.

The introduction of modern architecture to Srinagar coincided with a period of significant social and political change in India. Post-independence, as the nation sought to define its identity, architecture played a crucial role in this process. Modern architecture—with its emphasis on functionality, efficiency and the use of new materials like reinforced concrete—offered a departure from traditional design aesthetics. In Srinagar, architects confronted the unique challenge of reconciling these modern ideals with the city’s rich architectural heritage and the challenging Himalayan climate. The city’s distinctive geography, climate and sociopolitical conditions provided a canvas for some of the country’s most celebrated architects to create innovative designs.

The work of pioneering architects such as Achyut Kanvinde, Joseph Allen Stein and Shivnath Prasad exemplifies the fusion of the modernist architectural idiom with Srinagar’s cultural and environmental ethos. Their designs skilfully integrate natural light, climate-responsive forms and traditional Kashmiri craftsmanship. Exploring Srinagar's lesser-known modernist structures offers valuable insight into their enduring impact on the city's evolution.

Achyut Kanvinde (1916-2002): Functionality and Rationalism

Achyut Kanvinde, one of India’s foremost modern architects, was deeply influenced by the Bauhaus Movement and the teachings of his mentor Walter Gropius at Harvard University. His approach to design emphasised functionality, clean lines and the use of concrete as a defining material. In Srinagar, Kanvinde left a significant mark with several institutional and public buildings, including the iconic Broadway Cinema in the Badami Bagh Cantonment area. The theatre features a distinctive long-span concrete structure with wooden exterior cladding, a sloping roof and multiple small windows.

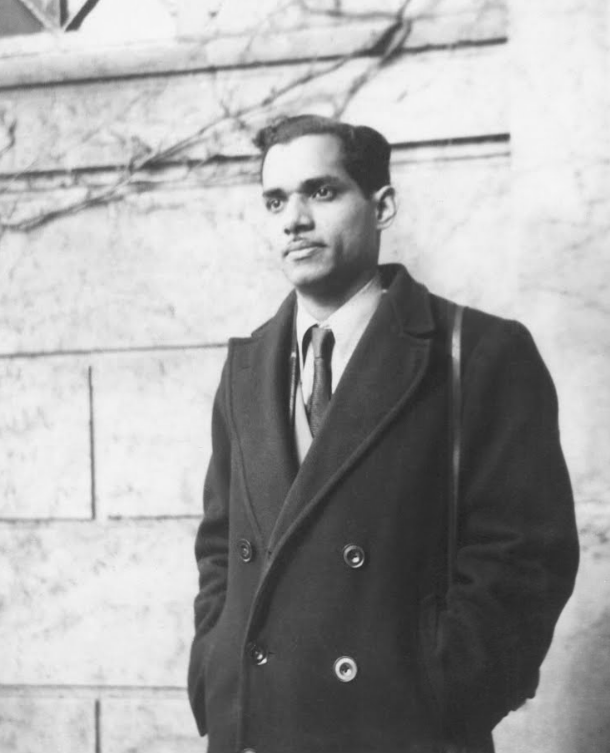

Achyut Kanvinde at CSIR, 1948. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Completed between 1979 and 1982, the Sher-e-Kashmir Indoor Stadium stands as a testament to Kanvinde's mastery in designing large-scale public venues. Commissioned by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir, the stadium features a space truss structure, utilising both steel and prestressed concrete, materials emblematic of modernist architecture. The stadium's thoughtful design incorporates natural ventilation and lighting, essential for maintaining comfort in Srinagar's variable climate. Strategically located near Iqbal Park in Wazir Bagh and seamlessly integrated into the surrounding landscape, the stadium has become a vibrant hub for sports and community events.

The stadium’s cruciform-shaped plan evolved out of the need for a stable structural form spanning the large playing arena to accommodate approximately 5,000 spectator seats in a column-free space. Through close collaboration with the structural designer and careful evaluation of alternatives, Kanvinde developed a single-layered space structure. A public concourse on the perimeter at the ground level provides for ticket booths and refreshment counters. Practice halls and warm-up areas are provided in the basement, beneath the seating areas, while supporting facilities like changing rooms and toilets are housed in pyramidal modules located outside, adjacent to the main structure. The use of locally sourced materials and construction techniques not only optimised costs but also resonated with the region.

Beyond these projects, Kanvinde contributed to several other notable projects in Srinagar, including the Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (1975; which remained unrealised) and the Dairy Development Board (1986) on Gupkar Road. His designs for engineering headquarters (1966) and high-altitude research laboratories (1969) further highlight his versatility in adapting modernist principles to diverse institutional needs.

Joseph Allen Stein (1912-2001): Crafting Contextual Modernism

American architect Joseph Allen Stein pioneered a regional modernist approach to Indian architecture, particularly through his work in New Delhi and West Bengal. His renowned designs include the India International Centre (IIC) and India Habitat Centre (IHC) in New Delhi. Stein’s practice is distinguished by its exceptional sensitivity to local contexts, climates, nature and cultural nuances.

The Sher-e-Kashmir International Conference Centre (SKICC). (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

SKICC. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

Designed with care, the Sher-e-Kashmir Stadium uses natural ventilation and lighting to adapt to Srinagar’s changing climate. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

SKICC fuses exposed brick, earthy textures, and climate conscious design rooted in Kashmir’s landscape. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

SKICC features clean lines and open forms. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

Stein’s most notable contribution to Srinagar is the Sher-e-Kashmir International Convention Centre (SKICC), designed with remarkable sensitivity to the landscape (Dal Lake and precinct) and local materials. He is also credited for the selection of the site; reportedly specifically recommending a lakefront location. His meticulous planning ensured harmonious integration with the Zabarwan mountain range and Dal Lake. Completed in 1977, the complex comprises a conference centre and a hotel. The conference facilities are grouped in a structurally symmetrical configuration, the block supported by eight massive piers and interlocked beams. The exterior is a precisely articulated concrete frame, expressive of the structural scheme. While the walls are clad with concrete blocks of exposed green aggregate, crushed from local stone, the roof is clad with blue-grey local slate.

Stein's engagement with the region extended beyond this landmark project. He was commissioned to prepare the Masterplan for Gulmarg's orderly development (1965) as well.

Shivnath Prasad (1922-2002): Bridging Tradition and Modernity

Architect Shivnath Prasad’s designs often showcased a sophisticated interplay between geometric precision and vernacular influences.

Architect Shivnath Prasad’s design for Allama Iqbal Library blends form, light, and landscape. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

Architect Shivnath Prasad’s design for Allama Iqbal Library blends form, light, and landscape. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

Allama Iqbal Library. (Picture Credits: Sheikh Intekhab Alam)

In Jammu and Kashmir, Prasad’s notable work includes the Allama Iqbal Library, built between 1969 and 1973 on a 1.5-hectare site inside the Kashmir University campus. The building features a square plan, with 9,375 square metres of built-up area. Pyramid-shaped skylights incorporated in each structural grid provide uniform illumination throughout the library interior. The design also includes drainage spouts to channel rainwater from the terrace, while brise-soleil elements protect the windows from exposure to the sun and rain. To capture the scenic splendours of the mountain ranges and maximise natural light, Prasad deliberately enlarged the glazed openings. The staircase and lift towers add verticality to the structure, creating a dramatic contrast to the rugged profile of the mountains. The reinforced concrete-frame structure of the building with exposed shuttering patterns adds much-needed textural interest to the facade.

Way Forward

Recognising Srinagar’s modern architectural heritage is essential, as these structures mark the city’s transition into modernity while showcasing their creator’s innovative design approaches. However, decades of political instability and neglect have rendered many public buildings inaccessible or obsolete. The absence of legal protection and heritage status has further endangered these structures, making them vulnerable to demolition in favour of high-rise developments. Despite these challenges, efforts such as heritage walks, academic research and media campaigns can revive public interest in Srinagar’s modernist buildings. As Srinagar marches toward rapid urban transformation, it is imperative to recognise, protect and celebrate this heritage.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).