Himroo, a textile tradition developed in the historic city of Aurangabad, embodies a legacy of exquisite craftsmanship and cultural significance. This centuries-old craft, known for its intricate patterns and luxurious texture, reflects the convergence of Persian and Indian artistic influences. It originated when Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq shifted his capital from Delhi to Devagiri (now Daulatabad) during the fourteenth century, bringing with him skilled weavers who introduced techniques of weaving luxurious fabrics to meet elite demand for blended silk clothing.

The name himroo is derived from the Persian word hum-ruh, meaning ‘similar’ or ‘alike’, referring to its resemblance to the kinkhab fabric (brocades of silk woven in gold and silver threads, mostly patronised by royalty). Over time, these artisans adapted their craft to local materials and preferences, creating the himroo weave we know today—a unique texture, both durable and visually captivating. It emerged as a cost-effective alternative to expensive brocades only accessible to few.

Weaver sits at a pit loom for Himroo weaving process. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

From the times of Muhammad bin Tughlaq and Deccan Sultanates to the Mughal Empire, particularly under Aurangzeb’s rule, himroo gained prominence and found a thriving export market in West Asia. With the decline of the Mughal and Maratha Empires in the early eighteenth century, the craft flourished under the patronage of the Nizams of Hyderabad. However, with industrialisation, changing market demands during the British rule and the shifting sociopolitical landscape during the Second World War and its impact on trade, the demand for such luxurious fabrics waned. By the 1940s, only 150 artisan families were known to practise the craft, a number that fell to just 30 after India’s Independence.

Weaving Technique and Characteristics

Himroo weaving involves interweaving silk and cotton threads on a pit-loom to create a soft, durable fabric with a satin-like finish. The process begins with naqshbandi, the preparation of a design directly on threads, now drawn on paper, to guide the handloom and create the patterns.

Imran Qureshi shows traditional naqshas. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

A collection of old naqshas. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Weaver setting up weft and warp threads on the loom. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Woman seated above the second weaver directs the threads being woven. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Weaver working the loom. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

The craft employs a double-reed handloom for weaving, with the reed—a comb-like tool—used to separate warp threads, guide the shuttle and position weft threads into place. Traditionally artisans worked on a pit-loom, also known as pagar loom (double-sided loom), where locally sourced cotton bana (weft or horizontal threads) and silk tana (warp or vertical threads) threads were interwoven to create elaborate designs. The weaver sits below in the pit working the loom, while the helper sits above to handle the dori (thread). The fabric is distinguished by its double-layered structure. The warp threads are woven in two layers, with the weft threads interlacing between them. This creates a unique, almost three-dimensional effect, adding depth and texture to the fabric. The fabric’s characteristic sheen and texture emerge from the interlocking pattern created with overlapping silk and cotton threads.

Bobbins of coloured threads. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

A shuttle with weft yarn thread. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

The essential tools for himroo weaving include:

-

Pirns – A small, tapered bobbin used to hold weft yarn

-

Fly Shuttle – A device carrying a pirn that passes through the warp threads to create patterns

-

Charkha – A spinning wheel that winds yarn onto pirns and bobbins.

Himroo Textile with floral patterns. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

The threads undergo careful dyeing, often using natural colours. Each motif requires specific warp and weft calculations. Depending on complexity, weaving a single metre of fabric may take up to a week, while completing an entire piece can require months. Traditional patterns include jali (latticework), bel (creepers) and gul (flowers)—motifs often in use for generations. Some designs echo the frescoes found in Ajanta Caves, highlighting regional influences on the craft.

A Family Legacy

Imran Qureshi, a 49-year-old master weaver with over four decades of experience, continues his family’s weaving tradition in Nawabpura, the locality famous for himroo production. Taking pride in his family’s centuries-old legacy, Qureshi shared, ‘My ancestor Muhammad Yakub Sahib, with other weavers, shifted to the region when the capital was shifted during the fourteenth century.’ His forefathers were renowned for creating intricate jangla (meandering floral patterns) and butidar (floral sprigs) himroo fabrics that adorned royal weddings and ceremonial robes. He recalls when the production team of the film Mughal-e-Azam visited his grandfather’s workshop while crafting costumes for Dilip Kumar’s role as Shehzada Salim.

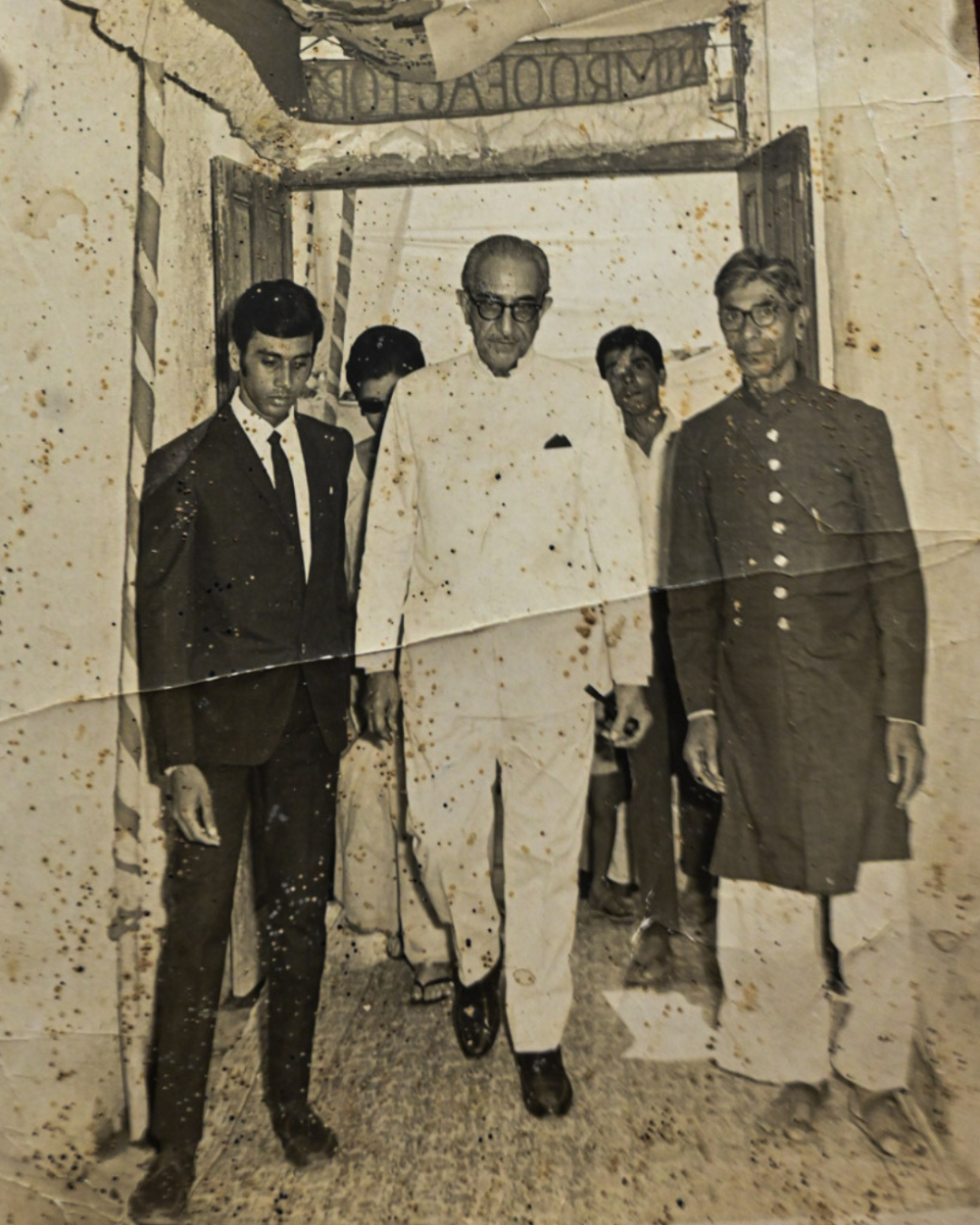

View of Himroo Factory in its earlier years. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Entrance of Himroo Factory and Haveli of Late Abdul Rauf Qureshi in Nawabpura. (Picture Credits: Late Rafat Qureshi)

Imran Qureshi’s father demonstrating the Himroo Weaving process. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Imran Qureshi shows a collection of designs used in their Himroo Factory. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

For many of these weavers, the craft remained a closely guarded family tradition, passed down from fathers to sons. ‘My great-grandfather, Haji Gulam Ahmed, still had 150 looms in the early twentieth century. Despite the decline in demand by the 1980s, my father Ahmed Syed Qureshi had a karkhana (workshop) in Nawabpura with about 25 looms, which employed more than 50 artisans. I learned the art of weaving—a craft that demands patience, skill and a keen eye for detail—from my father on the traditional tana-bana (handloom) when I was only eight years old,’ Qureshi explained. He went on to comment on how the landscape of demand and patronage of the craft has evolved over time—from royal dignitaries like Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, who visited their karkhana in 1956, and India’s first president, Dr Rajendra Prasad to a niche clientele primarily based outside India today.

Dignitaries visiting Himroo Factory. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Dignitaries visiting Himroo Factory. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

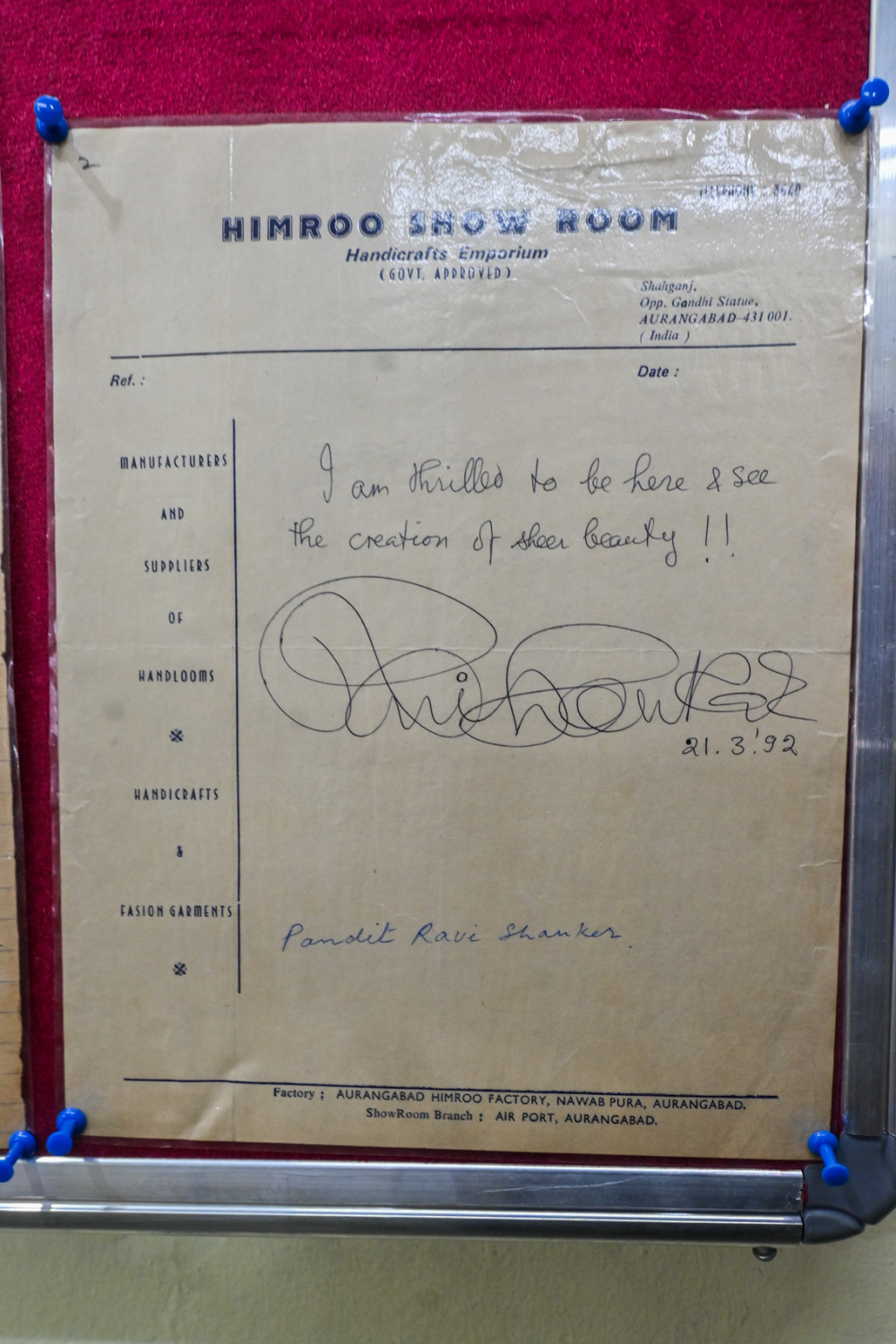

In 1992, Pandit Ravi Shankar wrote, “I am thrilled to be here & see the creation of sheer beauty.” (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

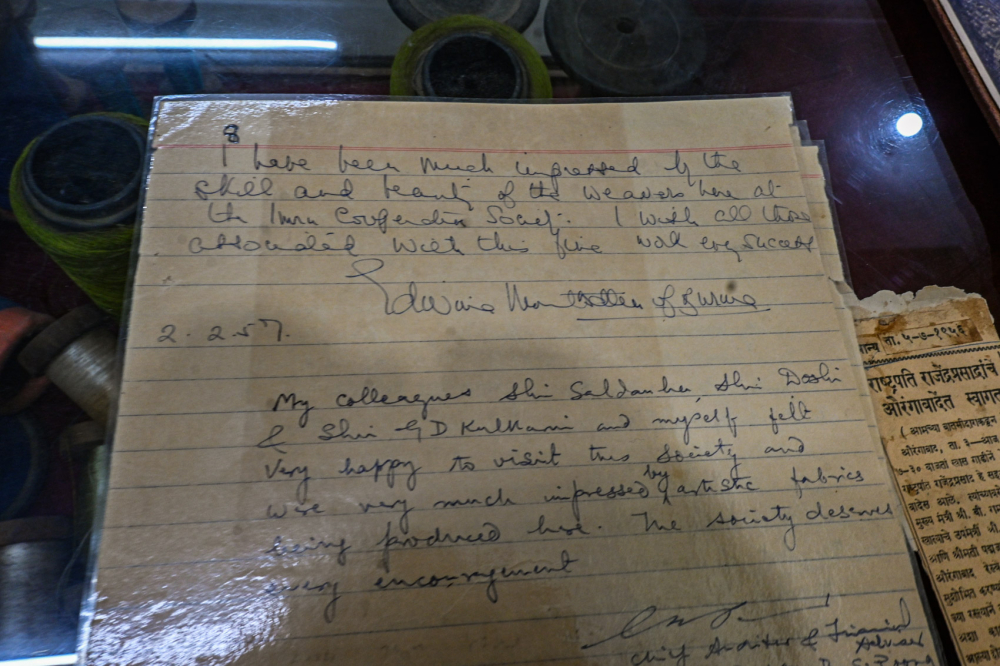

In 1957, Edwina Mountbatten wrote that she’s impressed by the skill and beauty of the weavers at the Himroo Co-operative Society, and concluded with “I wish all those associated with this fine work every success.” (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

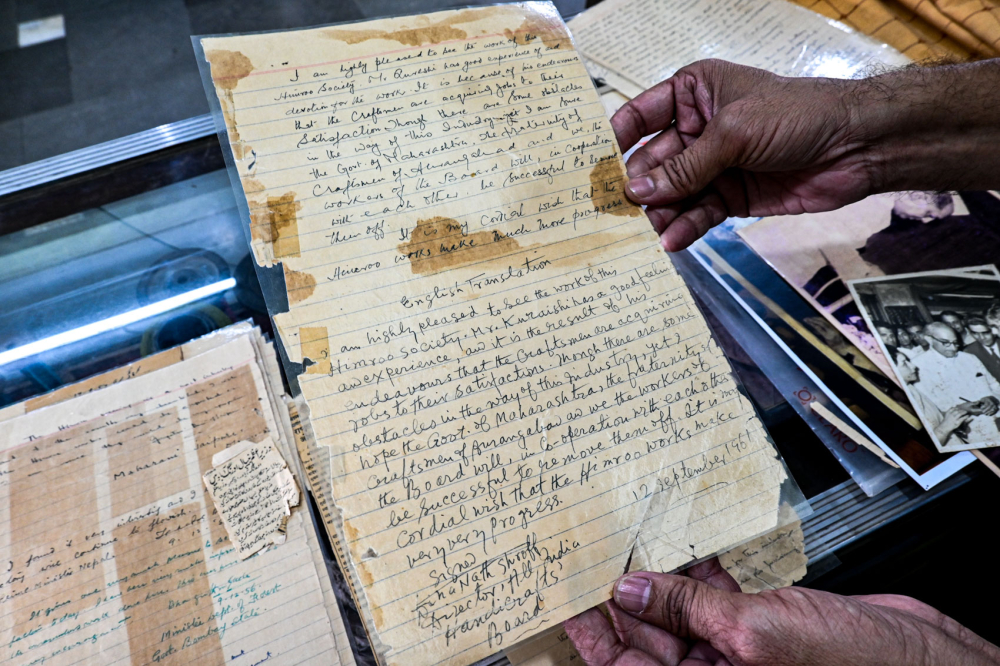

In the image is a comment left in 1961 by Dina Nath Shroff, Director, All India Handicrafts Board. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Medals awarded to Imran Qureshi’s family over the decades. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Despite its historical significance and exquisite craftsmanship, the production of himroo faces numerous contemporary challenges. In the words of Qureshi, ‘The market is flooded with machine-made imitations that are cheaper but lack the soul of handwoven himroo. These imitations lack the finesse and authenticity of handwoven fabric but dominate the market due to their affordability.’ He continues, ‘The craft involves a painstakingly slow technique. The traditional loom we use allows us to weave elaborate patterns that demand precision and creativity. It has become increasingly difficult to find skilled artisans willing to continue this labour-intensive work due to low financial returns. Many young people from our community are abandoning their roots, as they prefer jobs that offer better pay and financial stability.’

Reviving Himroo

Weavers at Imran Qureshi’s Himroo Factory. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Given the challenges of the current times, various individual and non-profit initiatives, alongside government programmes, have aimed to revive the craft and ensure its survival. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, with only one loom remaining operational, a determined Imran Qureshi connected with Mohammad Yaseen, a 75-year-old skilled weaver, to train a group of 22 women from underprivileged backgrounds for eight months, hoping to inspire a new generation of weavers. This project, accomplished in collaboration with the INTACH Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, was focused on including women, given they had been historically absent from the narrative of this craft. Ten out of the lot have chosen to continue this work with Qureshi in his Nawabpura workshop, creating products such as stoles, shawls and upholstery that appeal to modern sensibilities while preserving traditional techniques, ensuring a renewed interest in the craft. ‘The future of Himroo lies in awareness and support. When people understand its craftsmanship, they value it more,’ says Qureshi.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).