Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar found itself most prominently in the news in 2023 for its name change from Aurangabad—the name change being one of the last decisions Uddhav Thackeray took as chief minister of Maharashtra, before stepping down. In the debates that ensued either arguing for or against the change, two historical figures emerged supreme—Aurangzeb and Sambhaji, after whom the city’s previous (Aurangabad) and current (Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar) names derive. Who often gets lost in this discussion of Maratha (Sambhaji) vs Mughal (Aurangzeb) and either dynasty’s claim on the city’s history, is another figure, Malik Ambar, an African who settled in the Deccan and established the original settlement beside the Kham stream, where the city stands today.

Life and Career of Malik Ambar

For one person to advance clear from slave to peshwa as Ambar did, however, was exceptional. But then, he was an exceptional person.

–– Richard Eaton

Born as Chapu, in the Kembata region of Southern Ethiopia, Malik Ambar would forge an illustrious career as a military general and as a kingmaker in faraway Deccan (in southern India). Though his early life remains largely unknown, his journey began as a slave. Richard Eaton notes that Ambar found himself in Baghdad having been sold to a merchant who “recognising Chapu’s superior intellectual qualities, raised and educated the youth, converted him to Islam, and gave him the name ‘Ambar’.” While on a trip to the Deccan with his master, Ambar was purchased by the Peshwa (prime minister) of the Nizam Shahs in 1571 CE, himself a slave form Ethiopia. The Deccan at the time was governed by four sultanates: the Nizam Shahs of Ahmadnagar, the Qutub Shahs of Golconda, the Adil Shahs of Bijapur and the Imad Shahs of Berar.

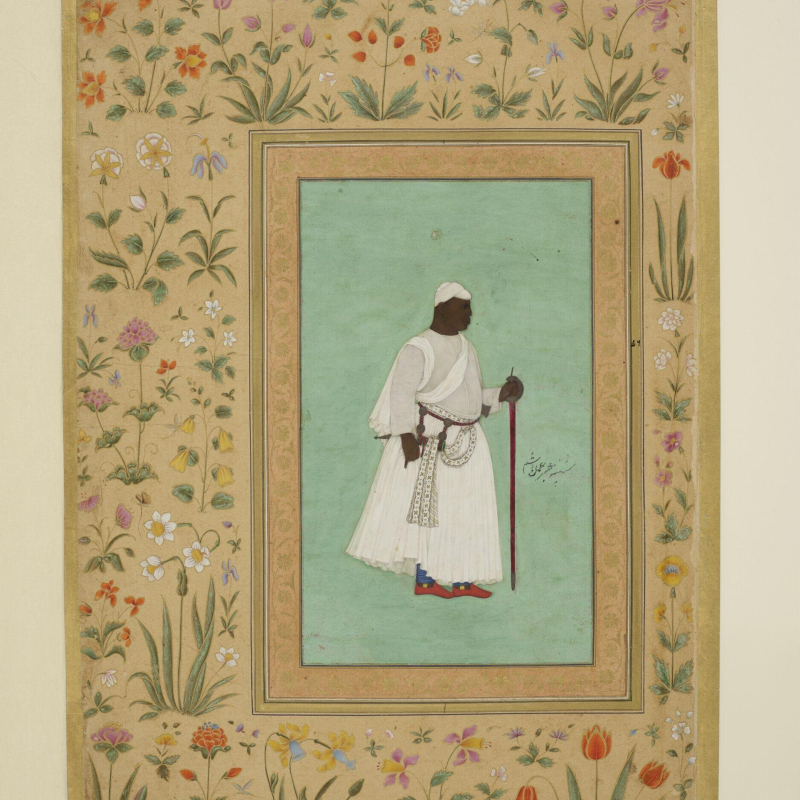

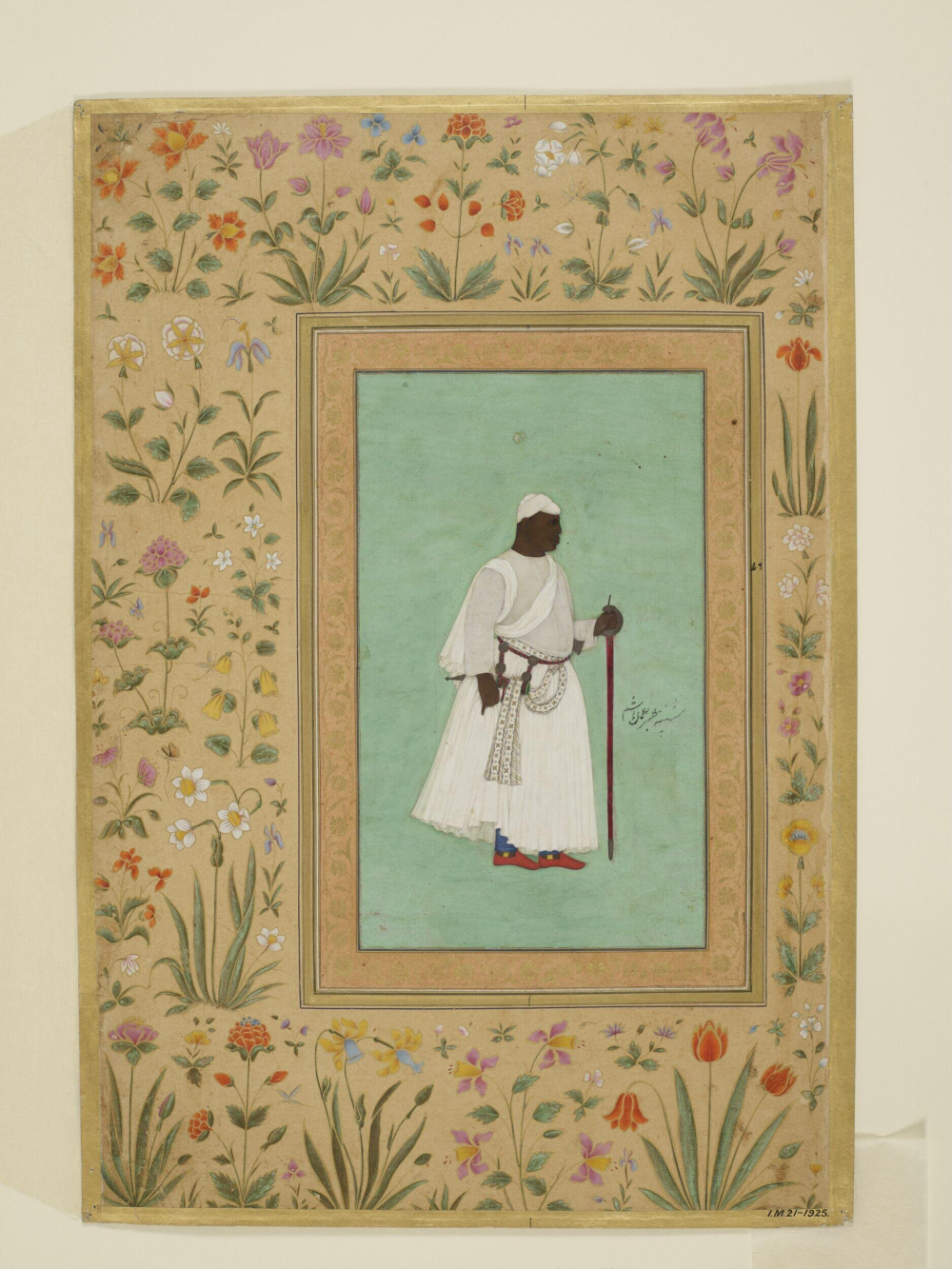

Portrait of Malik Ambar, by Hashim, ca. 1622-1623. (Picture Courtesy: Victoria and Albert Museum)

Tomb of Malik Ambar, Khuldabad. (Picture Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When his master, the Peshwa, died four years later, his widow granted freedom to Ambar. He then became a military freelancer, initially serving the Adil Shahs in Bijapur, where he commanded a small contingent and earned the title ‘Malik’, meaning ‘king’. In 1595, citing insufficient support, Ambar left Bijapur’s service with his 150 troops and returned to Ahmadnagar.

By 1600, the Mughals under Akbar had grown to include much of northern India, Gujarat and Bengal, and now sought control of the Deccan. Though they captured Ahmadnagar Fort, their authority remained restricted to the vicinity of the fort itself. In the hinterland, former soldiers of the dynasty, Malik Ambar being one of them, retained control and constantly challenged Mughal sovereignty in the region. This period of instability in the state proved especially fruitful for the ambitious Ambar who wanted the Mughals out of Deccan. To help his cause, Ambar installed a pliant nephew of the previous Nizam Shah ruler, further securing his position through the marriage of his daughter to the new ruler. Consequently, Ambar declared himself the Peshwa and fought in the Nizam’s name against the Mughals. At the time, Ambar’s military strength grew to an impressive 7,000.

The local Marathi-speaking population formed an important part of Ambar’s operations. As Eaton writes, by 1624, over 50,000 Marathas were serving in various cavalry units of Ambar’s army. Ambar also employed guerilla warfare tactics to harass the much larger Mughal armies, a strategy later perfected by Shivaji. Interestingly, Shivaji’s grandfather, Maloji, served as one of Ambar’s chiefs, while his father, Shahaji, would carry on the cause of the Nizam Shahi dynasty after Ambar’s death. All this put together puts into context Eaton’s characterisation of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate under Malik Ambar to be effectively a ‘Maratha-Habshi’ enterprise.

Ambar died peacefully in 1626, having successfully kept the Mughals at bay in the Deccan, and was succeeded by his son as the Peshwa of Ahmednagar. Upon his death, Mutamad Khan, the chronicler of his fiercest rival, the Mughal Emperor Jahangir, recorded:

In warfare, in command, in sound judgment, and in administration, he had no rival or equal. He well understood that predatory warfare, which in the language of the Dakhin is called bargi-giri. He kept down the turbulent spirits of that country, and maintained his exalted position to the end of his life, and closed his career in honour. History records no other instance of an Abyssinian slave arriving at such eminence.

The Founding of Khadki

A map of the Neher’s (water channels) various tributaries and blueways looks uncannily like a modern Metro Rail plan: it consists of twelve lines with numerous “stations” and “interchanges” designed to reach as much of the city as possible.

–– Jonathan Gill Harris

Malik Ambar’s growing influence as Ahmadnagar's Peshwa and de-facto ruler culminated in 1610 when he founded a city along the Kham stream. This was not only the year he took back Ahmadnagar Fort from the Mughals but also the period wherein he defeated his rival within the Ahmadnagar nobility, Raju Deccani, securing his position as Ahmadnagar’s undisputed leader.

While smaller settlements such as Ellora, Rauza (present-day Khuldabad) and Daulatabad Fort always existed, the region’s arid climate and water scarcity had prevented the establishment of a major capital. The name given to the new city, Khadki, meaning ‘rocky’ in Marathi, itself attests to the nature of the land—a rocky landscape surrounded by mountains. Even these earlier settlements had invested heavily in water provisioning systems sufficient for their scale.

For Ambar, the main challenge in building a new city was provisioning it with adequate water. His solution emerged from a curious mix of factors. According to Jonathan Gil Harris, his childhood in a similarly water-scarce mountainous region in Ethiopia (Kembata), his youth in the man-made oasis of Baghdad with its sophisticated Abbasid-era aqueducts, combined with his knowledge of the Deccan gained over the years, gave him the vision to execute such a momentous task. Just as the Ahmadnagar state relied on maritime trade networks with Persia, Central Asia and East Africa for labour, Ambar leveraged these connections to obtain hydrological knowledge. Using this knowledge of Baghdadi aqueducts, he built a canal system that drew water from numerous streams and lakes in the surrounding countryside through channels called nahars. The channels had a combination of elevated and underground sections. The most famous channel from Ambar’s period is the still semi-functional Nahar-e-Ambari, which brings water from Harsul Lake and ends at a reservoir located in the compound of Maulana Azad College Guest House.

The construction of these nahars likely combined imported Persian/Arab aqueduct design and local engineering expertise working with foreigners. The locals had a long history of water management in dry land, evident in the water cisterns of Ellora, used to harvest rainwater. This aligned with Ambar’s genius for tapping into local expertise, be it military or artisanal.

The result was remarkable. Khadki flourished into a city with palaces, fountains and avenues, divided among fifty-four quarters, home to 200,000 people at its peak. As Eaton notes, some of the quarters were even named after Ambar’s prominent Maratha generals such as Malpura, Khelpura, Paraspura and Vithapura, reflecting the collaborative nature of his governance and the city’s development.

Structures from his time

Of Malik Ambar’s Khadki, little remains today. While subsequent Mughal and the Asaf Jahi rulers expanded the city’s structures and limits over time, several key structures endure, offering a glimpse into Ambar’s capital city.

Bhadkal Darwaza. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Bhadkal Darwaza: The Bhadkal Darwaza is one of the most prominent structures that survives from the time of Malik Ambar. Made up of black igneous rock, it served as the principal gateway to the city of Khadki. The gateway, according to Pushkar Sohoni, dates to 1612 CE and is reminiscent of the architectural style of the Bahmani sultanate.

Place of coronation of Asaf Jah I in 1720, Naukhanda Palace. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Naukhanda Palace: Diagonally across from the Bhadkal Darwaza lies the former Naukhanda Palace, now the Women’s College of Aurangabad and the Model High School. This palace once served as the principal residence of Malik Ambar, although today no structures from Ambar’s time have survived. Of the historical structures that do remain (dateable to the eighteenth century) are a Darwaza (gate) and a pavilion. In this pavilion, Nizam ul-Mulk, the then governor of the Deccan, declared himself independent from the Mughal empire and proclaimed himself Asaf Jah I. The Asaf Jahi dynasty would go on to rule the region, first from Aurangabad and then from Hyderabad till 1948.

Jami Masjid. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Interior of Kali Masjid, City Chowk. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Jami Masjid and Kali masjids: The masjids built by Ambar have remained in use over the centuries. Located right across Azad Maidan, the Jami Masjid is the grandest among the three and was erected by Ambar in 1612 CE. Originally built with only five central bays in the prayer hall, Aurangzeb later expanded the structure, adding three bays on each side of the original five, bringing the total to 11 bays. The interior of the central hall is five bays deep, with seven domes. Unfortunately, these domes are not visible unless seen from a distance.

A total of five Kaali Masjids, local neighbourhood mosques attributed to Ambar’s period, dot the old city—in Juna Bazaar, City Chowk, Shah Bazaar, Nawappura and one close to the Jami Masjid. Typically, these mosques have a prayer hall three bays wide and 15 meters deep. The similar construction of these five has led Dr. Sohoni to suggest that they might have been built by the same guilds/artisans.

Chitakhana. (Picture Credits: Anil Purohit)

Chitakhana: The Chitkhana is a palatial structure built on a large octagonal plan. Today, it houses a part of the Municipal Corporation of Ch. Sambhajinagar, otherwise known as the Town Hall. It is two storeyes tall and capped by a red-tiled trussed roof, reminiscent of many Neo-gothic roofs in Mumbai. This was an addition during colonial-era renovations, when the space was converted for use by the municipal offices. The palace has four main entrances, one on each side, each with a three-bay composition. Its central courtyard was earlier supplied by one of Ambar’s nahars, which was blocked by the alterations of the site in the colonial period.

Conclusion

Ambar’s building of a vibrant multicultural city and integrating global influences into a water-scarce region should be instructive to us today in the age of religious polarisation and climate change’s worsening effects. His story reminds us that the region’s history transcends simple binary narratives of Maratha versus Mughal.

Bibliography

-

Express News Service. (2024). Aurangabad and Osmanabad finally renamed as Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar and Dharashiv. The Indian Express. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/aurangabad-osmanabad-renamed-chhatrapati-sambhaji-nagar-dharashiv-8465248/ (Accessed: 9 November 2024).

-

Eaton, R. M. (2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives. Cambridge University Press.

-

Ibid., p. 105.

-

Eaton, R. M. (2006). The Rise and Fall of Military Slavery in the Deccan, 1450–1650. In I. Chatterjee & R. M. Eaton (Eds.), Slavery and South Asian History (p. 116). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-

Pillai, M. (2018). Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji. New Delhi: Juggernaut Books, p. 157.

-

Harris, J. G. (n.d.). The Slave Who Built a City. Sarmaya. Available at: https://sarmaya.in/reads/slave-who-built-a-city/ (Accessed: 9 November 2024).

-

Khan, M. N. (1994). Emergence of Khirki as Aurangabad (Summary). Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 55, 426–428. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44143390.

-

Eaton, R. M. (2006). The Rise and Fall of Military Slavery in the Deccan, 1450–1650. In I. Chatterjee & R. M. Eaton (Eds.), Slavery and South Asian History (pp. 117–123). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-

Sohoni, P. (2015). Aurangabad with Daulatabad, Khuldabad, and Ahmadnagar. Mumbai: Jaico Publishing House and Deccan Heritage Foundation, p. 30.

-

Murayi, Y. (2016). Water in Ellora - Khuldabad – Daulatabad. Marg, 68 (1), 133–134.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).