The Mughal gardens of Kashmir stand as some of the most significant cultural and natural treasures of the region, attracting visitors from across the globe. Built after the Mughal Empire established control over Kashmir in 1586 CE, these gardens are a testament to the Mughals’ exceptional ability to integrate art, architecture and nature into spaces of breathtaking beauty. These gardens represent the concept of an earthly paradise—a notion deeply rooted in Islamic philosophy and design, embodying the universal appeal of the ‘Garden of Paradise’ across the Islamic world. While this ideal predates Islam, it finds a unique discerning expression in Islamic architecture, poetry and garden design.

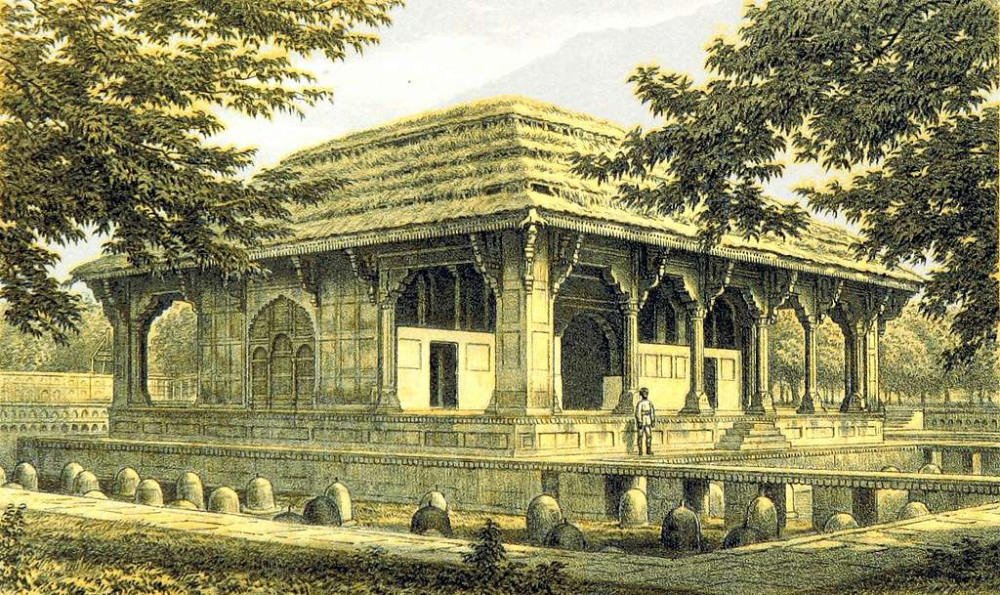

Sketch of the pavilion in the Shalimar Garden in Srinagar, published in The Happy Valley: sketches of Kashmir and the Kashmiris ... With maps and illustrations. 1879. (Picture Courtesy: British Library/GetArchive)

Marble pavilion of the Shalimar Garden. (Picture Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In Kashmir, the Mughal gardens serve as iconic symbols of this paradise-inspired vision. Carefully chosen sites were transformed into masterpieces of harmonious design, where the natural and man-made elements blend seamlessly. The layouts of these gardens commonly follow the Chahar Bagh or Char Bagh plan, in which a central water channel divides the space into four quadrants. This symmetrical design is adorned with lush foliage, often featuring orchards, and includes intricate water features such as pools and cascades. The Mughal architects used water both as a functional necessity for maintaining the gardens and as a central aesthetic element, emphasising symmetry, serenity and the sense of divine order.

Each Mughal emperor brought unique innovations to these gardens, particularly to ensure a reliable water supply that could sustain their paradisiacal creations. Typically situated at the foothills of mountains, these gardens showcased the Mughals' ingenuity in managing the challenging mountainous terrain. They maximized the potential of the natural landscape and water resources. Thus, the Mughal gardens were not merely decorative spaces but a blend of functionality, aesthetics, and symbolism.

Also Read | Kong Posh: Beyond the Crimson Stigma

Akbar, after annexing the Valley of Kashmir, envisioned Kashmir as a garden, or bagh, and celebrated its beauty by planting gardens laden with majestic chinar trees. However, it was Emperor Jahangir (and Empress Nur Jahan) who made Kashmir integral to the Mughal aesthetic imagination. The sacredness of springs at Verinag and Achabal inspired Jahangir to adorn these ancient sites by expanding or laying out gardens around them. The Achabal garden was dedicated to Nur Jahan, who also became co-sovereign during Jahangir’s reign. This garden was named after her as Begumabad. Though the tradition of laying gardens came into prominence during Jahangir’s reign, it was Shah Jahan who was responsible for creating some of the most iconic Mughal baghs in Kashmir.

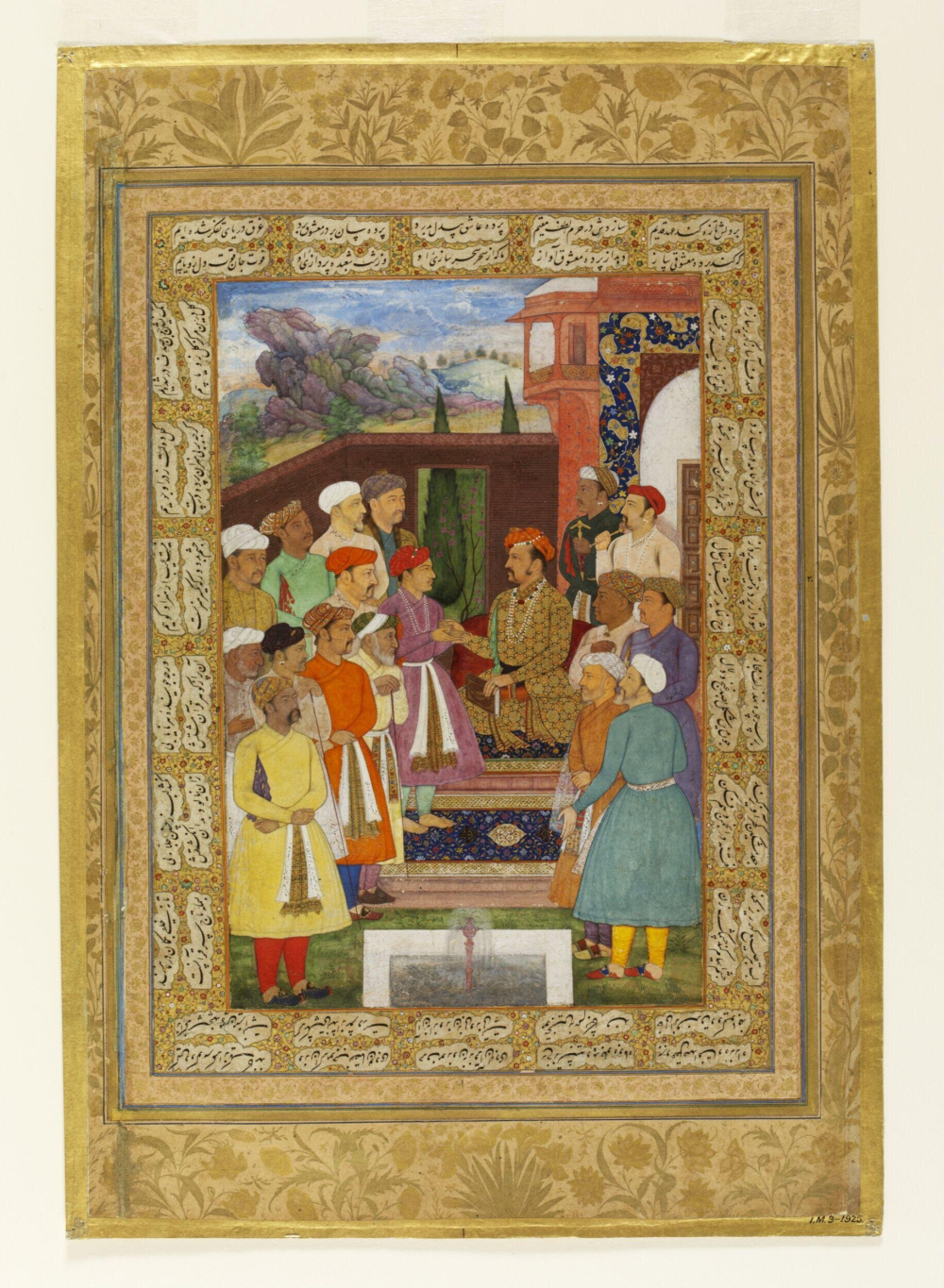

Painting by Manohar, depicting Jahangir receiving his son Prince Parviz in a garden in the presence of courtiers, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Mughal, ca. 1610-1615. (Picture Courtesy: Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

A manuscript of Padshahnama. (Picture Courtesy: Royal Collection Trust/Wikimedia Commons)

Mughal historians such as Abdul Hamid Lahori, who chronicled the reign of Shah Jahan, documented several of these gardens in his Badshahnama. The gardens mentioned by Lahori are set up around lakes, springs and more specifically at the foothills. Out of these, the surviving gardens in more or less their original setting are Shalimar, Nishat, Chashma Shahi, Pari Mahal, Verinag and Achabal. Some of the prominent gardens mentioned that survive only by their names recorded by Lahori include:

-

Bagh-i-BaharAra

-

Bagh-i-Illahi

-

Bagh-i-Aishabad

-

Bagh-i-Noor Afshan

-

Bagh-i-Safa

-

Bagh-i-Shahabad

-

Bagh-i-Murad (near Dal Lake)

-

Bagh-i-Afzalabad

-

Bagh-i-Zafar Khan (on Khushal Sar)

-

Bagh-i-Feroz Khan (on the Jhelum River)

-

Bagh-i-Khidmat Khan (on an island in Dal Lake)

-

Jharokha Bagh (in Manasbal)

Beyond their aesthetic and architectural grandeur, the Mughal gardens of Kashmir have long served as sanctuaries for spiritual introspection. Sufi orders, in particular, found in these gardens a perfect setting for quiet reflection. Discerning visitors continue to experience these transcendent qualities, highlighting how Mughal garden design deftly merges worldly beauty with an otherworldly sense of peace. During the Shahjahani period, Prince Dara Shikoh and Princess Jahanara, influenced by their mystical orientations, set up gardens to serve as abodes for Mulla Shah, the eminent spiritual teacher and renowned Sufi of the Qadri order. Additionally, both owned personal gardens within the royal Mughal city in Srinagar, Nagar-Nagar and outside the city along the banks of Dal Lake. Dara or Jahanara also sponsored a garden on the banks of Anchar Lake for Mulla Shah, which still goes by the name Mulla Shah Bagh.

Pari Mahal, commissioned by Dara Shikoh. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Gardens in Arts and Literature

The Mughal gardens of Kashmir were immortalised in art and literature. Shah Jahan’s court poets, Qudsi Mashhadi and Abu Talib Kalim Kashani, composed splendid Persian verses celebrating Kashmir’s landscapes and gardens. These poems captured the transcendent beauty of the region:

Talib Amuli

به گلشنش چو درآی بغل گشوده درآی

که هر طرف صف حور است در لباس حریر

When you enter its gardens, spread your arms in a wide embrace,

For there are rows of houris everywhere, dressed in finest silks.

Bagh-i-Nishat, on the eastern side of the Dal Lake. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Entrance channel to Shalimar Bagh from Dal Lake, 1864. (Picture Courtesy: Samuel Bourne/Wikimedia Commons)

Qudsi Mashhadi

ندارد دهر، جای دل فروگیر

به از باغ جهانآرای کشمیر

ز فردوس است خرمتر، نهادش

ز آب خضر روشنتر، سوادش

No better place where the heart may seek joy,

Than the world-adorned gardens of Kashmir.

Its essence, more delightful than paradise;

Its waters, brighter than Khizr's spring of life.

In later centuries, Persian literary traditions were enriched by Urdu poetry. Hafeez Jalandhari’s 1930s magnum opus Tasveer-i-Kashmir celebrated Kashmir’s gardens as timeless symbols of joy and beauty:

Come, let me show you the attainment of eternal joy,

Morning in the Garden of Breeze (Bagh-e-Naseem),

Evening in the Garden of Delight (Bagh-e-Nishat).

Preservation and Conservation Efforts

The major surviving Mughal gardens in Srinagar include Shalimar Bagh, Nishat Bagh, Chashma Shahi and Pari Mahal. Beyond Srinagar, the gardens at Achabal and Verinag—located 65 and 85 kilometers away, respectively—also retain much of their original charm. Shalimar Bagh, built by Jahangir and Shah Jahan, epitomises Mughal indulgence and royal grandeur, while Nishat Bagh was commissioned by Noor Jahan’s brother, Asif Khan, in 1633 CE. Chashma Shahi, constructed by Ali Mardan Khan, reflects Mughal mastery in integrating architecture with natural springs.

Inside view of the Marble Pavilion. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Inside view of the Marble Pavilion. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Chashma Shahi. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

The decline of the Mughal Empire led to neglect and vandalism of these gardens. Some restoration efforts began during Dogra rule (1846–1947 CE) and continued post-independence. In 1904, John Marshall, Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), documented these garden’s designs, offering invaluable insights into their layouts. Despite some colonial modifications, such as replacing fruit orchards with open lawns, the core structures of the gardens remain intact. However, all these efforts leave much to be desired.

In 2004–05, the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) was commissioned by the state government for undertaking a detailed survey and restoration programme. Architects led by INTACH conservation experts recommended reversing inappropriate interventions, restoring water channels and fountains, and retaining walls using traditional techniques. Notably, based on their recommendations, the hammam at Shalimar Bagh was transformed into a living exhibition space.

Long-term Approach for Restoration

The preservation of Kashmir’s Mughal gardens remains an ongoing challenge, requiring expertise in historical landscape management and Mughal architectural practices. With sustained efforts, these ‘gardens of paradise’ can continue to inspire and captivate future generations, celebrating the timeless harmony between nature and culture. Kashmir’s mountainous topography and seasonal variations demand careful ecological stewardship, a principle that resonates from the Mughal era to the present day. Historically, streams and springs were ingeniously channeled to feed intricate waterworks, sustaining lush orchards and seasonal blooms. Today, however, the pressures of urban sprawl, water scarcity, unsustainable tourism, and depleted expertise and human resource pose significant threats to this delicate balance. The interventions and conservation efforts must, therefore, adopt a holistic approach—restoring the built fabric and landscapes, while aiming at restoring traditional irrigation systems and mitigating environmental impacts—to preserve both the natural fabric and cultural legacy.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).