In the winding, narrow lanes of the old city of Srinagar, the legacy of Kashmir’s rich artisanal heritage still lingers. While well-known for its exquisite wood carvings, vibrant papier-mâché and exquisite pashmina shawls, this area has long nurtured lesser-known yet highly sought-after crafts as well. These traditional art forms, passed down generations, were once integral to Kashmiri identity and thrived as flourishing industries. However, in recent decades, these conventional crafts have faced numerous challenges. In an era dominated by mass production and shifting consumer demands, artisans who once took great pride in their laboriously created works are now struggling to keep such traditions alive.

Ghulam Mohammad Zaz: The Last Santoor-Maker

In the heart of Srinagar, close to the ancient Zaina Kadal bridge, a small, nearly deserted workshop still echoes with the sounds of the hammer and the chisel. This is the domain of Ghulam Mohammad Zaz, the last traditional santoor maker in Kashmir. At 75, Zaz is a living example of a person who has dedicated his life to a craft that few can now appreciate or perpetuate. The santoor, a 100-stringed instrument central to Sufi music and classical concerts, is deeply rooted in Kashmir’s musical traditions. Once favoured by the Sufi community and the royal court of Kashmir, it became an integral part of the region’s culture. Zaz, who inherited this craft from his forefathers, has been crafting these delicate instruments for over six decades.

The art of making the santoor, once a thriving craft in Kashmir, now fades into obscurity as few artisans remain to carry it forward. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Ali Mohammad Giru, a master craftsman, revives the fading art of khatamband. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

His workshop, filled with the smell of walnut wood, is a sanctuary from the traffic noise outside, where he painstakingly shapes and tunes each instrument by hand. ‘It’s about creating something that carries a soul, a resonance that speaks to our heritage,’ says Zaz, emphasising the profound nature of his craftsmanship. He also went on to explain that the santoor gained prominence through artists like Pandit Bhajan Lal Sopori and Shiv Kumar Sharma, who introduced the instrument into the Indian classical music scene.

Today, Zaz is deeply conscious of the possibility that he may be the last of his family’s santoor-makers. He doesn’t have any sons to carry on the family business; and his daughters’ varied career choices reflect a broader trend in Kashmir, where younger generations are abandoning traditional crafts in favour of more secure, lucrative occupations. Despite receiving the prestigious Padma Shri award from the Government of India in 2003, Zaz is concerned for the future of the craft and observes, ‘Awards are recognition, but they do not guarantee the survival of the art.’

Reflecting on the award, Zaz expressed bittersweet feelings about it, ‘I wasn’t as happy as I thought I’d be. It would have been more meaningful if the award had been given to my late grandfather, as he was the true hero of this art.’ He continued, ‘Unfortunately, the art of santoor-making may soon be lost, as the younger generation is unwilling to continue it. Crafting a single santoor takes immense patience and time, sometimes days, weeks or even months.’

Ali Mohammad Giru: The Harbinger of Khatamband Renaissance

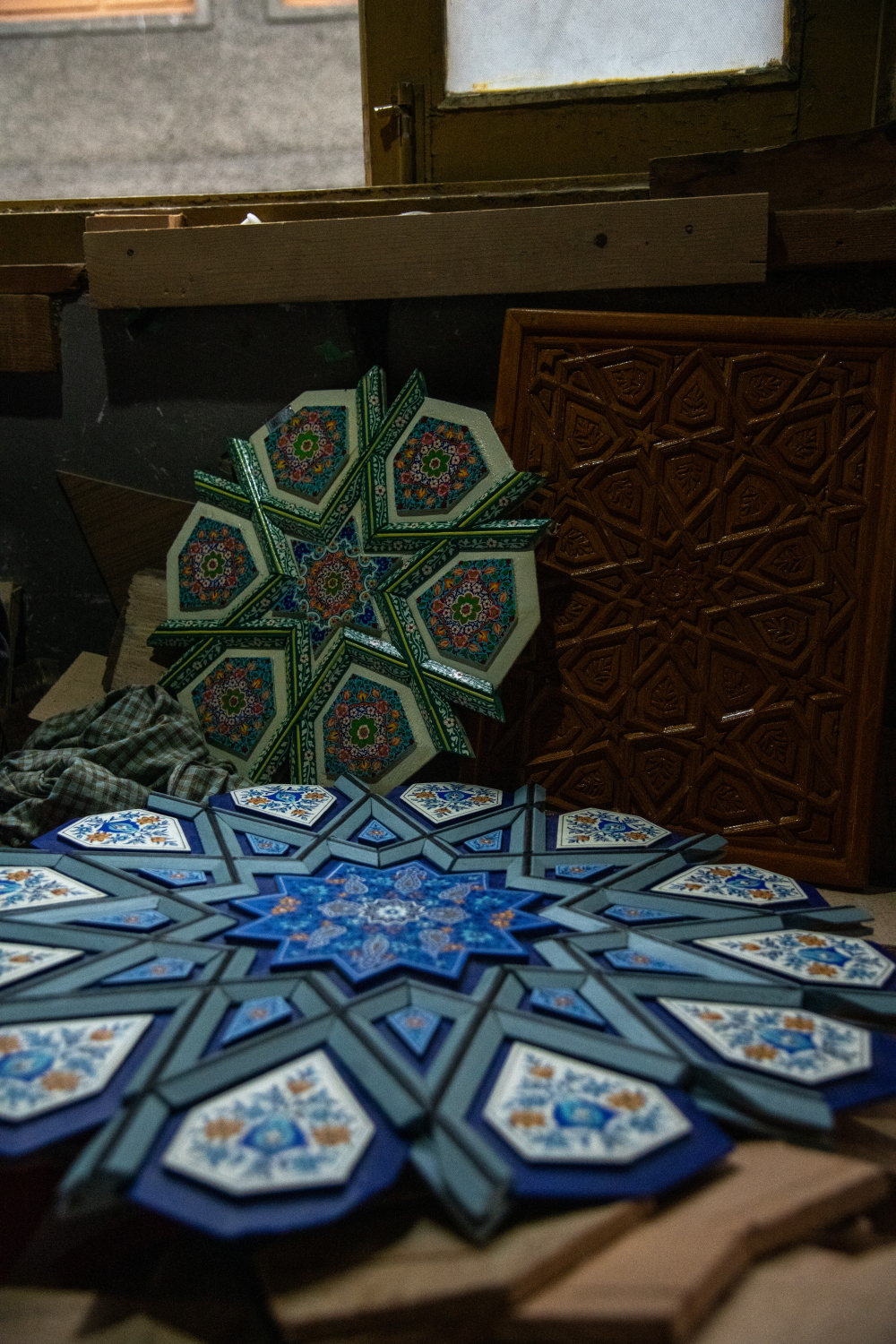

Katamband, a traditional Kashmiri interior design technique, which involves creating ornamental ceilings using tiny polygonal wood pieces fitted into geometric patterns and secured with beadings. In recent years, this artform has played a crucial role in restoring the valley’s medieval charm, even as modern concrete structures are rapidly replacing traditional household aesthetics. The old city’s marketplace and master carpenters are at the forefront of this design renaissance. Ali Mohammad Giru’s workshop in Safa Kadal, Srinagar, is a testament to this craft’s resurgence.

Ali Mohammad Giru, a master craftsman, revives the fading art of khatamband. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Ali Mohammad Giru’s workshop in Safa Kadal stands as a beacon of khatamband’s revival. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Khatamband’s vibrant geometric patterns blend tradition with timeless elegance. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Reflecting on the challenges encountered two decades ago, when the craft was almost on the decline, Ali Mohammad noted, ‘We entered the market at a time when it was completely indifferent to us.’ During those trying times, it was difficult to replicate khatamband and other allied designs, but today he is optimistic, ‘I am incredibly appreciative that even my highly educated children are interested in this, as it is my ancestral business, ‘Ali Mohammad remarked, highlighting the craft’s renewed appeal to the younger generation.

Mohammad Hanief: The Last Turquoise Jewellery Artisan

The once-flourishing art of Kashmiri turquoise jewellery-making is now on the brink of extinction. Mohammad Hanief, a 65-year-old artisan from Srinagar, is one of the last surviving craftsmen engaged in this centuries-old craft. His small workshop in Fateh Kadal is filled with all sorts of tools of the trade and embodies the rich legacy of this traditional craft.

Mohammad Hanief, one of Srinagar’s last turquoise jewelry artisans. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Turquoise stones are skillfully crafted into intricate jewelry by the artisan. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Handcrafted turquoise jewelry. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

In its heyday, Kashmiri turquoise jewellery adorned royals and nobles, prized for its exquisite craftsmanship. Skilled artisans like Hanief would meticulously set turquoise stones into silver and gold, creating cherished heirlooms that were passed down generations. However, the trade has experienced a steep decline in recent years, and Hanief now stands a solitary practitioner of this dying craft. ‘After me, no one will carry this forward,’ he lamented, and further noted how the crafts diminishing economic viability has discouraged the younger generation from pursuing it as a livelihood.

Mehraj-ud-Din Bafanda: Aari Embroidery’s Struggle for Survival

In Noorbagh, Mehraj-ud-Din Bafanda’s workshop buzzes with artisans skilled in aari embroidery. This needle art, introduced in Kashmir by Persians in the twelfth century, is renowned for its intricate floral designs on various fabrics. Aari work is celebrated for its versatility, suited for all seasons and featured on a wide range of items, from suits, stoles, shawls to even home furnishings.

Aari embroidery workshop. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

‘This art is our legacy,’ reflects Bafanda, acknowledging how the craft has survived through tumultuous times. However, despite its enduring popularity in the fashion industry, the craft faces significant challenges. The rise of machine-made designs poses a serious threat to this traditional craft. ‘Customers prefer cheap machine-made designs,’ laments a middle-aged aari worker, highlighting the economic pressures faced by the artisans practising this craft. He also goes on to point out the role of government neglect in the decline of the industry.

Ghulam Nabi Dar: Walnut Wood Carving Legacy

Walnut wood carving furniture from Kashmir, renowned for its durable and intricate designs, stands among the region’s most-celebrated crafts. Ghulam Nabi Dar is a master woodcarver based in Safa Kadal, and his journey from an impoverished child labourer to a Padma Shri recipient is a testament to a craftsman’s passionate dedication to his craft.

Ghulam Nabi Dar, Padma Shri laureate and master walnut woodcarver from Safa Kadal. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Exquisite walnut wood pieces crafted by Padma Shri awardee Ghulam Nabi Dar. (Picture Credits: Syed Muneeb Masoodi)

Exquisite walnut wood pieces crafted by Padma Shri awardee Ghulam Nabi Dar. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Recalling the hardships of his childhood, Dar observed, ‘There were days when we didn’t have food to eat. I had dreams of studying, but circumstances made it impossible.’ So, leaving school post class 3, he started out as a young apprentice in the woodworking industry, which would eventually become his lifeline. Dar and his brother took up work with Abdul Razaq Wangnoo, a master wood carver, operating manual machines for a meagre salary of one rupee a day, which went towards sustaining their family.

He then moved to Abdul Aziz Bhat’s workshop, producing goods for the well-known Subla & Company. Bhat recognised Dar’s potential and taught him the art of walnut wood carving. Reflecting on his journey, Dar shared, ‘After a lot of effort, my work paid off. I pray to God for a long life so I can continue with this art.’

Farooq Ahmad Mir: A Legacy of Kani Weaving

Farooq Ahmad Mir, a 72-year-old master artisan from Srinagar, was honoured with the Padma Shri in January 2025 for his exceptional dedication to the traditional craft of kani shawl weaving. Born in 1953 in the Khaiwan Narwara area of Srinagar's old city, Mir began his journey into this ancestral craft at the age of 10, dedicating over six decades to mastering and preserving this intricate weaving technique, which involves weaving elaborate patterns using wooden spools known as kanis instead of a shuttle to create intricate pashmina shawls. Dating back to the Mughal era, the craft follows a talim script to guide weavers in forming elaborate motifs inspired by nature, such as paisleys, florals and chinar leaves.

Farooq Ahmad Mir, a Padma Shri awardee, honoured for his dedication to Kani Shawl weaving. (Picture Credits: Majid Mir)

Farooq Mir’s, and later his children's, commitment not only preserved this centuries-old tradition but also inspired a resurgence of interest among younger generations. Despite the challenges posed by modern manufacturing, Mir's unwavering passion has ensured that the legacy of authentic Kashmiri kani shawls continues to thrive.

Bashir Ahmad Dar: Carpet Weaving in Srinagar

A glimpse inside a carpet karkhana, with bundles of vibrant yarn awaiting the loom. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

A traditional carpet loom. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Hand-knotted Kashmiri carpets, known for their rich patterns and fine silk. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Carpet weaving, once a key industry in Srinagar, has seen a significant decline over time. Bashir Ahmad Dar, one of the few remaining weavers, offered a bleak picture of the craft’s future. ‘The younger generation has little interest in learning to make carpets,’ he says. Economic pressures, coupled with shifting market conditions have taken a serious toll on the livelihoods of carpet weavers. The financial rewards for this skilled craft have diminished to the point where artisans now earn significantly less than labourers in other sectors, with daily wages dropping as low as 250 rupees in the winter, creating a stark economic disparity. This struggle, thus, makes it increasingly difficult for traditional craftspeople to sustain their trade or attract new talent. As a result, the tradition of passing down skills through generations is fading, placing the survival of this ancient craft in jeopardy.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).