The period between 1200 CE and 1600 CE saw the rush of traders and navigators to several ports at Malabar, situated on the southwestern coast of India, as the demand for spices, especially black pepper, grew manyfold across the world. Sailing ships from various nations crisscrossed the Arabian seas, replacing an age-old Arab trading network. After the decline of the ancient ports at Muziris, Qulion, a new era of maritime trade and exploration was established with a trading hub in Calicut.

People gather to enjoy the sunset at Kozhikode beach. (Picture credits: Joseph Rahul)

The Zamorins (the anglicised name for the titular heads of the ruling dynasty) and their city of Calicut soon garnered fame from visitors and traders, both Eastern and Western. While it was indeed a city with some palaces, a suzerain as well as a cosmopolitan populace, after the entrenchment of the British at Malabar, these overlords of Malabar faded away from the public mind, leaving nothing but a few Palmyra scrolls extolling them and their reign. Though Portuguese, Dutch and Arab travellers left behind their accounts of Calicut, the first local account surfaced around the seventeenth century—Keralolpathi. This work, often referenced but rarely considered factual, interweaves lore and legends to recount the history of Cheranad (present-day central Kerala), beginning with the mythical Parasurama, followed by the Cheras and the Perumals, culminating in a record of the division of land among various chieftains by the last Perumal before his abdication and departure for Mecca.

The story of that final division ends with the mention of the gifting of a thicket of shrubs, near present-day Kozhikode (previously referred to by Arabs as Kalikut, later anglicised to Calicut), to two valiant youths from the erstwhile Nediyirippu family from Eranad, who previously aided the Perumal in winning a war. Along with the land, he bestowed his sword as well, with the edict and permission to conquer more territory if they wished to. Thus began the checkered tale of the Zamorins, the founding of Calicut, their rise to power in erstwhile Malabar, a vigorous reign spanning some 400 years or more, and their eventual decline into obscurity.

The Establishment of the Zamorins

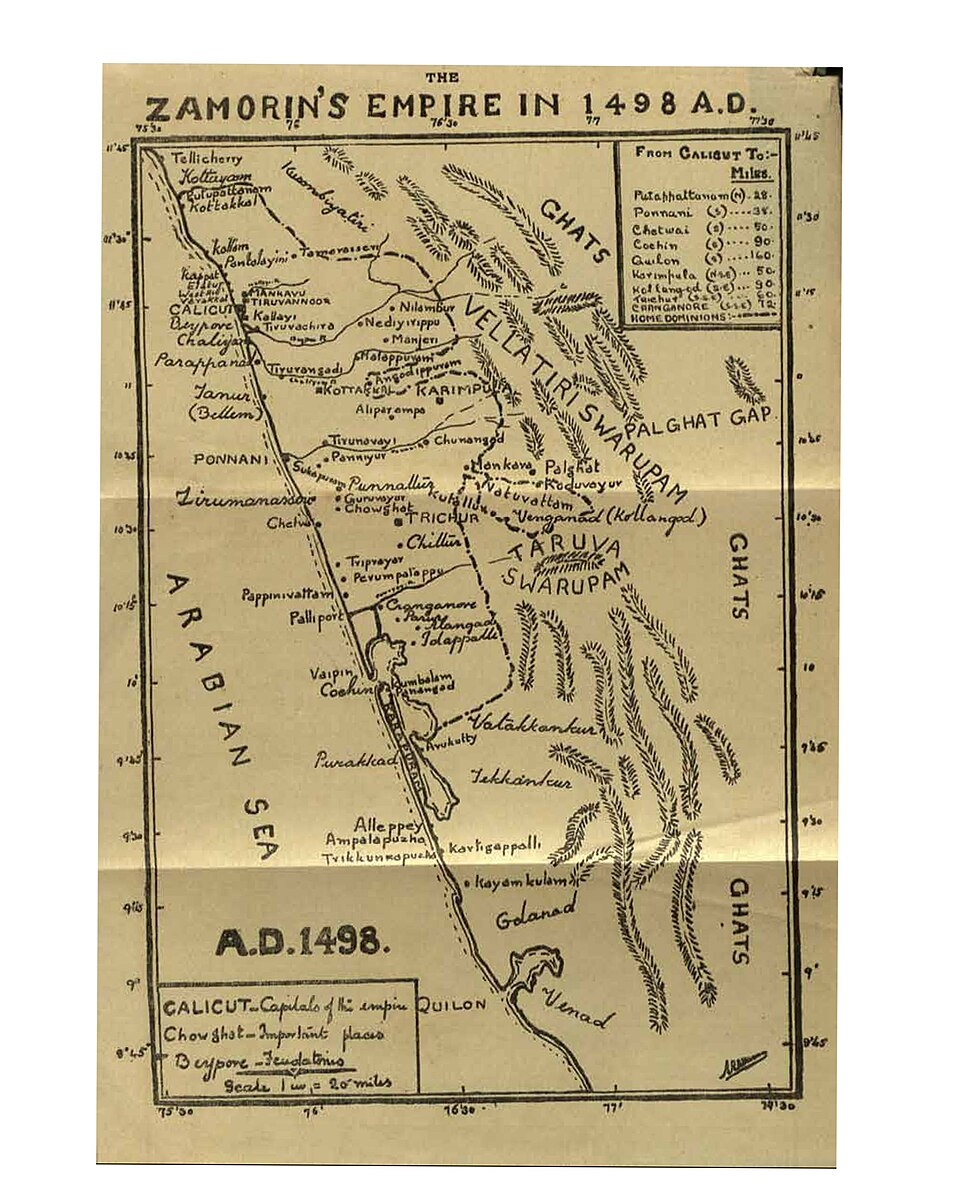

During the Chera rule in Kerala, the land was divided into various principalities or nadus, with Eranad in the present-day Malappuram district being one such principality. After the fall of the Cheras, the concept of larger independent areas, ruled by dynasties and called swaroopams, emerged. The Nediyirippu Swaroopam, originating from Nediyirippu in Eranad, became one of the significant political houses. Ambitious and desiring to expand, the Nediyirippu Swaroopam sought control over both a seaport and the Nila waterway (present-day Bharathapuzha) for growth. Around 1100 CE, the forces of the Eranad chief launched an offensive against Porlanad, ruled by the Porlathiris, located to the North of the Kallayi River. In addition to his armed forces, constituting men of the Nair community, the chief also gained the support of the trading Muslim community who had settled in the region. This alliance proved instrumental in defeating local chieftains, allowing the Eranad chief to acquire the territories around what is now Calicut, gain access to Kallayi and the interconnected river system for the transport of goods, and establish control over the Nila River and the port of Ponnani.

A Map of the Zamorin's kingdom. (Picture courtesy Archeological Survey of India/Wikimedia Commons)

A Trading City is Built

The exact date of Calicut’s founding is not clear, but it likely came into being between the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, which coincided with the growing wealth and influence of the Eranad Chief, who expanded their control southward and westward. By the fifteenth century, the Eranad chief came to rule over most of the area, between Kolathunad in the North and Tiruvadi (later Travancore state) in the South. After he established himself as the principal suzerain of the region, he adopted the title Swami Thirumalpad, which was further shortened to Samoothiripad or Samoothiri. This title was anglicised to Zamorin, over time.

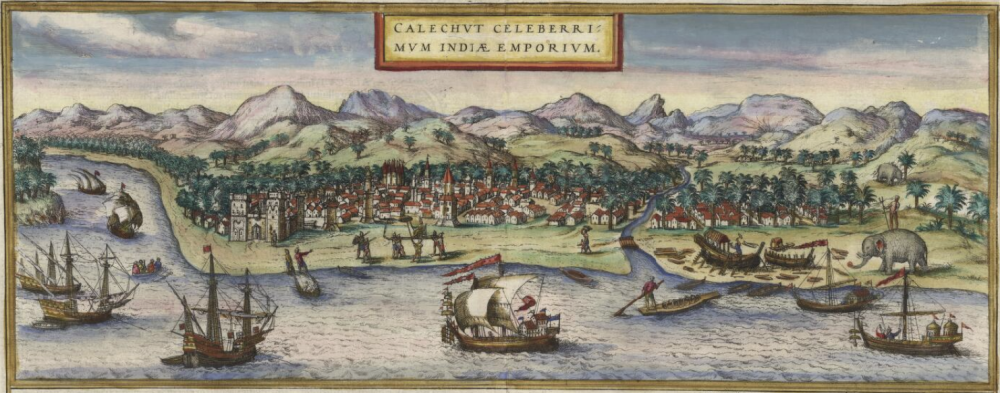

The Zamorin developed Calicut as the commercial capital, dividing his time between Ponnani and Calicut. A shahabandar (port manager) oversaw the prosperous port. Calicut was developed using a concentric square plan, adhering to traditional Vastu Shastra principles. The city’s core comprised the Big Bazaar or Palayam and the surrounding areas formed the early city, a layout reminiscent of the ancient Chola capital Kaveripoompattinam (present-day Poompuhar). Foreign enclaves were situated southwest of the main fort, housing Arabs, Jews, Turks and Chinese traders. Calicut was home to a large merchant population of Arab origin, and their descendants through marriages with the local communities, called Mappilas, aligned themselves with the Zamorin.

Political swings and the natural silting, which affected southern ports, led more traders to the new secure port (roadstead) of Calicut. This led to the establishment of an entrepôt, which served as the principal transshipment point for both far-Eastern goods as well as spices from the East. Arab traders arriving in Calicut could procure a diverse range of commodities in one place—pepper and ginger from Malabar; beads, jewellery, cotton and linen from Tamilakam; spices like cloves from the East; cinnamon from Ceylon; silks and porcelain from China. Calicut’s trade links extended to China, Cambodia and Indonesia, with Chinese markets being a significant focus. Regular visits by large Chinese treasure ships were commonplace in the fifteenth century, as recorded by explorer Ibn Battuta. The Zamorin’s thriving trade relationship was further solidified through the formal exchange of ambassadors between Calicut and the Ming Dynasty in China.

Conquests and Rivalries

Perpetual feuds between the Calicut and Cochin royals resulted in many wasteful wars, constantly draining the coffers of both kingdoms for over four centuries. Preoccupied with these petty conflicts, these rulers failed to notice the growing interest in their produce and wealth from nations across the seas. In Europe, profit margins were dropping, prompting merchants to consider bypassing the middlemen, in this case, the Arab traders. This economic motivation was compounded by religious tensions following the Crusades, which had pitted Christians against the Muslims.

The Arabs, who controlled the Arabian Sea routes as well as many trading ports, hitherto partnered with Venetian traders, facilitating the transport of goods from Calicut to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf ports, then to Alexandria and Venetian ports, before reaching consumers in Europe. However, as Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias discovered and Pêro da Covilhã, a Portuguese traveller and spy confirmed, there was a more direct sailing route to Calicut. Though difficult, this route involved circumnavigating the southern tip of Africa and then doing a slingshot trip across the Indian Ocean, sailing the monsoon winds to reach Calicut.

'Vasco da Gama before the Samorim of Calicut', by Veloso Salgado, Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, 1898. (Picture Source: Wikimedia Commons)

'Calechut Celeberrimum Indiae Emporium: Cum Privilegio,' Braun, Georg & Hogenberg, Frans & Braun, Georg, 1572. (Picture courtesy: National Library of Australia)

As the Portuguese king was contemplating this pioneering voyage, the trade dynamics in Calicut were changing, for the Arabs were finding it increasingly difficult to share trading space with the Chinese. The reasons for this tension remain unclear—it may have been because of Chinese Admiral Zheng He’s direct venture to Arabia and beyond, threatening to take over their sea routes. Whatever the cause, it appears the Chinese traders and community were ousted from Calicut.

The Portuguese Arrive

Vasco da Gama was tasked with sailing to Calicut and establishing contact with the Zamorin, and following a long voyage, he found himself stranded at Melinde, on the Kenyan coast, after rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Here he chanced upon Malemo Cana, a pilot who agreed to guide him to Calicut. In May 1498, Vasco da Gama’s fleet arrived at Kappad first and moved to Panthalayini, both roadsteads near Calicut, as the latter was more secure. Though da Gama went on to meet the Zamorin, he failed to secure a pepper monopoly and ended up alarming the Arab traders.

Following da Gama’s return to Lisbon, the Portuguese Crown, now financially backed by German trading houses, planned more voyages with the intent of monopolising trade with Calicut. These expeditions resulted in unnecessary violence, including the bombardment of Calicut, the chance discovery of Brazil, and a complete estrangement between the Portuguese and the Zamorins of Calicut. However, the Portuguese managed to establish a good rapport with the enemies of the Zamorin—the Kolathunad chief and the Cochin Raja, which resulted in their building of forts and factories in Cochin and Cannanore (present-day Kannur) to acquire spices.

To counter this threat, the Zamorin decided to strengthen his naval resources by enlisting the Marakkar Muslims, a sailing community previously engaged in rice trading. The Marakkars had relocated closer to Calicut from Cochin due to conflicts with the Portuguese. With support from Arab and Ottoman allies, they helped build the Zamorin’s naval forces. The Portuguese made another attempt to attack and subdue Calicut in 1510, under Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque, but the forces led by him and Marshal Dom Fernando Coutinho were repelled and forced to retreat.

Seeing that these wars were depleting their resources, the Portuguese finally decided to bypass Calicut and moved northwards to take over and settle in present-day Goa. Here, the Portuguese established Estado da India, the Portuguese State in India, and used their armed ships to blockade the seas, thus preventing Arab traders from shipping goods directly to Arabia. The Marakkar fleet of small boats attacked Portuguese shipping from time to time, and as friction escalated with frequent sea battles, the Marakkar and Mappila corsairs remained a constant threat to Portuguese interests in India.

Around 1600 CE, Portuguese priests in Calicut managed to sow the seeds of discord between the Marakkars and the Zamorin, resulting in a dramatic fallout that culminated in the capture and beheading of the Kunjali Marakkar IV, the famed head of the Marakkar clan.

Following these events, the Portuguese built a new fort in Calicut, strengthening their position in the region. However, this victory did not result in a stable alliance, and relations with the local communities remained tense and unstable until the arrival of the Dutch.

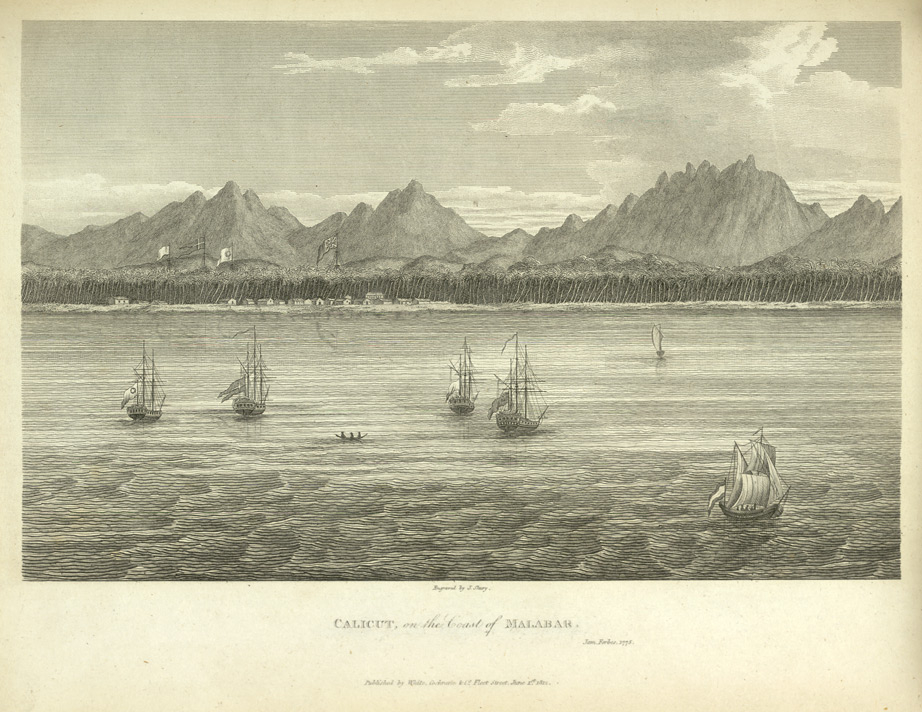

A Port in Decay, Shifting Trade

After the Portuguese, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a trading base in Cochin, with the help of the Cochin Raja, alongside larger factories in Ceylon and Indonesia. The Dutch and the Zamorin were at loggerheads, with the Dutch often supporting Cochin in their wars with the Zamorin. Meanwhile, Travancore also became a wary trading partner with the Dutch. At about the same time, the Zamorin was getting alienated, his position weakened due to declining trade, growing distrust with his one-time Arab allies and a depleting treasury. Despite this, the Dutch maintained limited dealings with the Zamorin.

Around the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, rising water levels submerged roughly 2-3 miles of the Calicut shoreline, especially parts of the city previously allocated to foreigners and trading communities. This and the sinking of the old Portuguese fort gave rise to questions about the port’s viability, hastening the departure of alarmed traders to other ports to the North, as well as the Maldives and Malacca. French travellers such as Rennefort, Dellon and others such as Fryer and Visscher, in their records, noted that the Zamorin was spending longer periods at Ponnani, visiting Calicut mainly for important occasions.

Mysore Conquest

By the eighteenth century, a new dynasty of Zamorins was created by adoptions from Neeleswaram, due to the lack of male heirs through the maternal line. A Zamorin conquest in Palghat (present-day Palakkad) forced the Palghat Raja to request military support from a rising power—Hyder Ali of Mysore. Subsequently, in 1746, Hyder Ali, with his cavalry and superior artillery, saw an opportunity to subdue the Malabar armies and proceeded to confront the Zamorin’s forces. The Zamorin’s forces were unable to match Mysore’s might and offered to withdraw and pay a ransom, but when he failed to do so, Hyder Ali’s forces attacked again in 1766. This time, faced with defeat, the Zamorin set his Calicut palace ablaze, choosing to perish in the flames. This fiery end marked the fall of the over 400-year rule of the Zamorins of Calicut.

The younger Zamorin princes, with some support from the British, continued resisting Hyder Ali, while the older family members fled South to Travancore. But as the Mysore army and its administrators established their control, the rebel princes were forced to negotiate pensions and retire. Following Hyder Ali’s death, his son, Tipu Sultan, took over the reins. Tipu attempted to exploit the riches of Malabar, but his wars with Travancore and, later, the formidable English resulted in his ultimate decline.

British Calicut

In 1792, Tipu Sultan, though aided by the French, was defeated by the British and forced to cede his territories, including Malabar, to the British East India Company. Malabar initially became part of the Bombay EIC territories before being transferred to the Madras Presidency. At this point, the exiled Zamorin families returned and resettled in British-administered Calicut, but with reduced status, receiving modest pensions and with limited tax collection responsibilities. The British continued to support the institution of a Zamorin, though only as a titular position.

Calicut, on the coast of Malabar, 1813. (Picture courtesy: James Forbes/Wikimedia Commons)

As time went by, Calicut became the district headquarters under British rule. The port became crucial for exporting teakwood, which was floated down the river from Nilambur, making it to Britain for the manufacturing of British warships. Seeing opportunities beyond spices and timber, the British also developed tea and coffee estates in the hills. The city saw much advancement with the coming of the British—including the opening of clubs, cricket matches being played at Mananchira, and horses and carts plying on the narrow tree-lined streets lit by gas lamps. Roads were paved as waterways gave way to road transport. Administrative offices and courts sprang up, and trade was resurrected, as Parsis, Gujaratis, Jews and Mappilas took up new business avenues, while the Nair community, hitherto used to fighting for a living, transitioned to overseeing agriculture and managing their serfs.

The change in British fortunes in Calicut was nothing short of amazing. In 1670, the British operated off a rented house serving as a factory with just three staff members. They could not even offer a decent dinner to a visiting pastor then, due to a lack of space and resources. Two centuries later, they were masters of the entire region.

Several British administrators were assigned to the region to extract wealth from the forests and farms, fields and handlooms of the region. A railway line was laid to Malabar, with its terminus at Beypore (later to Calicut), later extended further south, linking the region to the larger cities of India. The Mappila community remained restless and wary of the new administration that had taken over from the Mysore ruler, and a police force had to be set up to maintain control over them. A major incident exemplifying this conflict was the slaying of the Collector H.V. Conolly over his role in the exiling of Arab preacher Sayyid Fadhl.

Calicut in the Early Twentieth Century

Over time, sailing ships gave way to large ocean-going steamers, and as the Cochin port was built, the fortunes of Calicut declined further. One can, thus, observe how a thicket of bushes developed into a great city of medieval times, becoming a cosmopolitan enclave and how its fortunes ebbed and flowed, taking it to dizzying heights and down to what the British travellers in the nineteenth century recorded—a sleepy little town, a shadow of the great entrepôt it once was.

When you visit Kozhikode today, you will find no palaces, but you may chance on an old timer who still remembers its history, the stories of the Marakkars and the Chinese, of the duels and the festivals, and you will not fail to notice the communal amity in this multicultural city. That was always Calicut’s strong point.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).