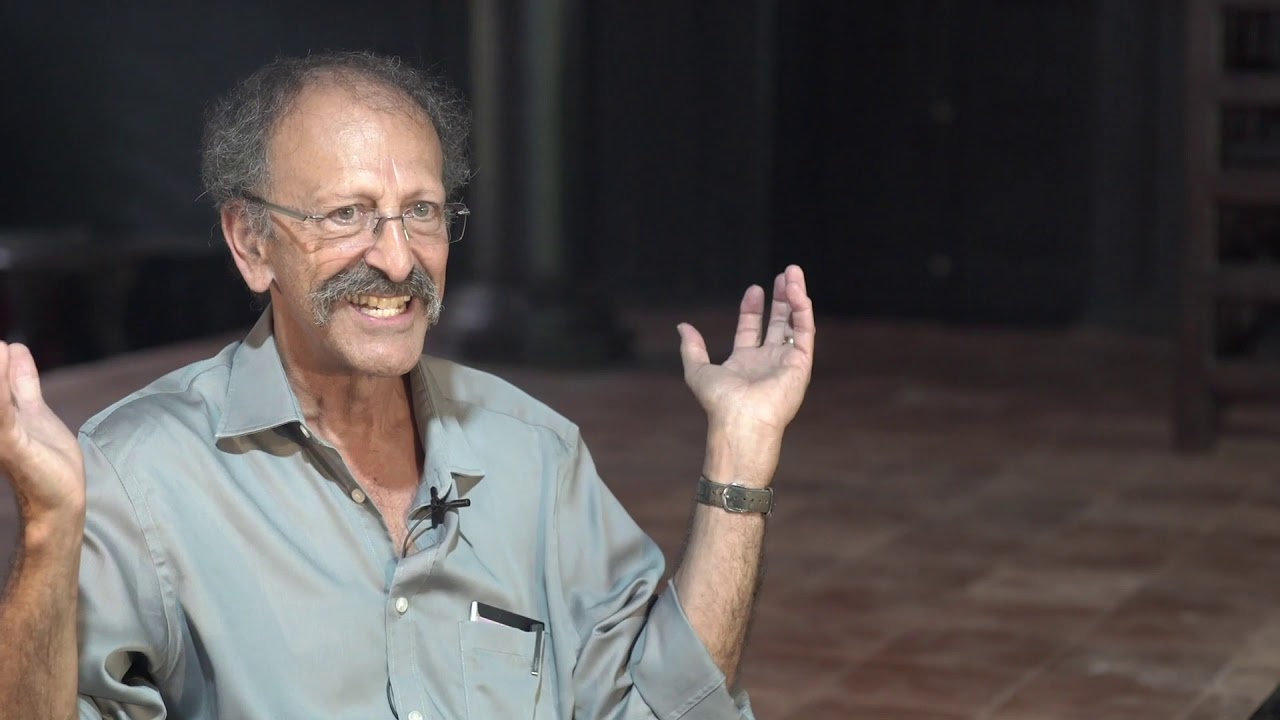

One of the foremost minds in the field of Indology and linguistics today, 69-year-old David Dean Shulman was born and brought up in Iowa in the Midwest, USA. After finishing school, Shulman immigrated to Israel and gained a BA degree in Islamic History from Hebrew University. He grew fascinated with Indian studies and went on to do a PhD in Tamil and Sanskrit at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, under his mentor and lifelong friend, John Marr. His dissertation was titled ‘Mythology of the Tamil Saiva Talapuranam’, and for its fieldwork he had to travel to Chennai (then Madras). Thus, began his long and deep infatuation with Tamil—the language, the people and the music. After he completed his PhD, he came back to Israel to join the faculty of Indian Studies and Comparative Religion at Hebrew University, from where he retired after a long, fruitful stint. At present, he serves the university as the Renee Lang Professor of Humanistic Studies.

David Shulman is bilingual, proficient in English and Hebrew, and has mastered Indian languages like Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, etc. He can also read several other languages like French, German, Persian, Arabic, etc. His book Tamil: A Biography, published in 2016, received critical acclaim and also met with criticism from some native quarters. Apart from Tamil, he has authored and co-authored more than twenty books on a vast array of topics, which include translations from ancient classical texts in Tamil and Telugu. He has published poems in Hebrew and has, to his credit, several academic articles. He received the Israeli prize, the country’s highest cultural honour, for his work on the literature and culture of South India in 2016. He is also known for his advocacy of peace in the politically turbulent region, and is the founding member of Ta’ayush, a joint Israeli-Palestinian peace movement.

Following is the edited transcript of the video interview with David Shulman conducted by Yigal Bronner at Iringalakuda, Kerala, in 2019.

David Shulman (DS): I grew up in a little town in the Midwest, in Iowa. Iowa is very flat. It is so flat that it is unusual to find even a slight hill. The result was for me, not only for me—it may be Iowa syndrome—I spent the rest of my life, after leaving Iowa, looking for places that had some kind of intensity, powerful taste and colour. In this little town, maybe because of what I said, there was a tremendous hunger for cultural activity, education and art. They were really important in Iowa. So, when an opera company happened to visit, I was about fifteen or fourteen, I don’t know, and they performed La bohème and the whole town came to see La bohème.

Yigal Bronner (YB): David, you have spent a lot of time writing about the meaning of great works, either works that everybody recognised as great, like Sriharsha’s Naishadhiya, Manucharitramu, or works that you have discovered and think are great, and you write about their meaning. What does it mean for a work to have a meaning? Who should have the adhikara, the right or authority, to interpret it?

DS: Every work of art has some kind of meaning. It is really a question of if we know how to read it or not, if we can hear and learn that meaning. And the adhikara may reside in people who have not been trained, with no Sanskrit erudition, or let us say in Telugu or in Tamil, but who have some sensibility that allows them to hear that meaning. Although, I have to say, it helps to have lived in India for long periods of time, to have learned the languages, and to somehow be in that milieu. I am happy you asked about the adhikara because I think there is a sense that in our generation and also in the past generations the art of reading these classical texts has been largely lost, and part of the loss comes from the fact that there are normative and prescribed ways of reading texts, especially within Sanskrit, and also filtering into the other languages. So people look for the meaning of a work of art through the prism of the Kashmiri Alankarashastra, which is a wonderful thing in its own right. There is no question about that. Nobody should think that I am indifferent to Abhinavagupta and Anandavardhana. I am not. I am fascinated by their theories. But I don’t think that they really help us in reading the texts, including the very ancient texts and certainly the medieval texts. So what does help actually? I could say that most of my teaching, my whole life, has been an attempt to somehow find, recover—usually together with people who are learning, students and colleagues, people like you—those lost protocols of reading. They have to be recovered because they have been lost to different degrees in the different literary cultures. In Tamil, for example, there is a severe break for all kinds of reasons, which largely have to do with the colonial period, when colonial values superseded the traditional ways of reading. It would only be a slight exaggeration to say that the last thousand years or so of Tamil poetry, an immense literature, has been largely forgotten, with one or two exceptions—like the Kamba Ramayanam, the Periya Puranam—partly because of the rediscovery of the old Sangam-period poems. Because antiquity became a value, that is a colonial value, people prefer to read those poems, and they have lost the ability to read the amazing works produced in a continuous way over the last many centuries. But it is possible to recover, I think, those modes of reading, listening and understanding if you read the text with patience. You have to know the language, you have to patiently read, and to keep asking yourself what it is trying to say. I should say I have a bias in this because I tend to prefer the notion of some kind of thematic and cognitive drive in the great literary works. I tend to feel that, for example in the Kutiyattam plays or in major works like Naishadhiya which you mentioned or the Kamba Ramayanam, there is a set of themes that if you read with an eye to finding them, the book will talk to you and tell you what it is wanting to say. Not in a didactic way, it is more some kind of exploration of a particular cognitive and thematic range. I could say that most of my life I have been trying to read like that, not alone but with the help of people who are close to me, Narayana Rao for example, and you.

YB: Is meaning like a fixed thing? Or is it also influenced by the political and social contexts of the time in which the work was created and the time in which the work is continued to be interpreted? I am thinking about your Tamil book and the kind of criticism it ran into in the modern Tamil readership that has a different set of values and a different set of protocols of reading than the ones you are trying to recover. Is recovery really the way to go about it?

DS: Recovery is a metaphor. It is like recovering the Vedas when they were stolen by the demons and hidden in the bottom of the ocean. It is an image of some kind of rediscovery; maybe rediscovery would be a better word than recovery. There is absolutely no question that all of these works exist in a historical setting, of course. In fact, even to put it into those terms is to create a false dichotomy, to say there is the work and there is the economical, social and political context and all of that. As if the text and the context were two different things. But actually it is not like that, the context is fully alive and active and embedded in the text, and also the other way around. So one always has to find out some way to understand. For example, in the sixteenth century, thinking of the listeners or readers of the literary works—it is also true of music or painting or sculpture, or drama or architecture—why were consumers of these products, who were also in many cases the authors of those products, suddenly offering something that was unprecedented and new, as if there was a shift in artistic taste. I think there was such a shift and we want to understand why this happened, why this readership had changed and who they were. Having said that, I also want to say that, of course, nobody would ever say that they really understand the one and only meaning of Hamlet or any of the masterpieces in these languages or in Sanskrit. Meaning has to be invented perhaps in each generation. But I think there is something to be said for our adhikara. People living today, who are reading these books, are finding that they actually do speak to us in a very, very powerful way. And the reason I can say is that I know from my own experience in my body that I am profoundly moved by what I might see on the Kutiyattam stage, or by the books that I am reading. I have a physical reaction, and I tend to believe that these physical reactions are good indicators of something that is really there in the texts.

YB: Like in the plays themselves.

DS: Yes. Like in the plays because there too they are going through all kinds of very physical reactions. Emily Dickinson has a beautiful sentence where she says: ‘How do I know if I am in the presence of a great poem? I know it because my entire body is on fire and my head is as cold as ice. Is there any other way to know it?’ That is exactly right.

YB: There is a lot that you do that is also a political activity. Is there any relationship between your political activism and your scholarship, are they like two separate domains with a strict bifurcation between them?

DS: I have never been any good at compartmentalising myself. I am just not good at it. I know that some people can do it. But I cannot do it. I think that the work in the Palestinian territory is like watching Kutiyattam in some sense. They belong together. I can give you some examples. Again, if you think in terms of the experience, what happens to a person, let us say, in the Palestinian territory when soldiers are barking at you or threatening to arrest you, or maybe they are actually arresting you. There is violence directed at innocent Palestinian people and at the activists. Sometimes, not always, it depends on how one responds. Suppose you stand up to it, and you say no, you will not go along with what they are telling you to do, there are moments like that. There is something in the inner experience of that, it is an involuntary thing, but you begin to feel good inside. You experience a kind of sense of liberation. Even while being arrested, you feel free. That is again the other kind of knowing that is so interesting to me. You could say also, if you wanted to, as somebody who works in Indian materials and who has read Gandhi, and knows about the Gandhian method, that also has a part in what we do in the territories. It is a form of Gandhian-style non-violent resistance. I think that Gandhi amazingly created on an experimental basis his method and theorised it also and made sense of it. That is his huge achievement. So that is somewhere in the background of what I do. But I don’t think it is the primary drive.

YB: But if you look at the scholarly side of things, this field is also politicised to a great degree, especially in India, when Sanskrit studies and the humanities more generally are so taken over by dangerous politics. What is our role as scholars in these dark days?

DS: Our role is to speak the truth, and speak the truth to power. It can happen in all levels, and sometimes in what appear to be rather peripheral places like the classroom. But actually there is another thing that we have learned over the years of political activity. You cannot calculate the consequences of what might appear to be a seemingly minor and irrelevant act of goodness. And truth is like that if you speak the truth, and truth also includes those protocols of reading—reading in a non-mechanical way, reading in some personal way, reading with humanistic values that are implicit in the sources accessible to us today.

YB: In sixteenth century South India, for example, what do these humanistic values consist of primarily?

DS: To answer that I have to generalise in a kind of far-reaching way. I don’t much like that. I am always interested, above all, in the very specific, in the singular, you might say, but nonetheless it is impossible to answer that question without saying something of a general nature. General means, I think that all of South India, and maybe also beyond, in the North, all of the South Indian linguistic, cultural matrices shared a set of common cultural features and were taking part in this shift in taste that I was talking about. The shift in taste is an indication of some kind of systemic change. So we find new themes and values in all of the literatures, if you want to stay with literatures, that is in Telugu and Tamil, Malayalam and in Kannada, in Sanskrit, also in South Indian Persian, and probably also in Marathi and Odia. So what are these values? For example, there is a fascination with the unencumbered individual, the person who has left behind his or her ascriptive identity, and is living on the basis of some kind of highly personal, idiosyncratic, very individualistic of taste. There are things one could say about how all this develops, why it develops to this point. It doesn’t emerge out of nothing; it comes from a long background, but it becomes incredibly present in the sources. If you read the poems of Annamacharya or Annamayya in Telugu, or if you read the Tamil Naishadhiya, or if you read the Malayalam so-called Manipravalam Campus and, in Kannada, if you read Ratnakaravarni, for example, and there are many, many more examples, you will see there is a fascination with the recalcitrant, stubborn individual. I don’t want to say you can’t find things like that in the early literature. There is no question about it. Nevertheless, there is a shift in that direction. It also should be said, since we are in the first half of the twenty-first century, I suppose I have to say, and I believe it anyway, that the gender balance has shifted, that there is a very rich, and possibly new sensibility that relates to women and their imaginations, their actions and their feelings. The fact that 90 per cent of Telugu padams are put in the female voice—that tells you something, and also that voice has a particular, very confident quality about it. It doesn’t mean that the women were living in some kind of liberated mode in the sixteenth century; they were not. But there is some imaginative shift in the nature of these male and female voices. Also, I see it in Kutiyattam, that is another area where the female voice is very present, perhaps in a new way. I should say that although Kutiyattam is a very ancient tradition—there is no doubt that it has lines going back to the very beginning of Indian drama, the Natyashastra—I tend to agree with Manu Devadevan, who has written in his dissertation and later too, when he says that he thinks Kutiyattam, as we now know it, crystallised in the sixteenth century. I think that perhaps is correct. It includes the nature of those female roles.

Along with those ideas, there is a new kind of kingship or actually several new types of kingships. The traditional, what you could call the dominant Chola model, of what a South Indian state looks like, was clearly shifting in a new direction. It is not always the same thing and not necessarily even a universal thing at that time. But all these states, the Nayaka kingdoms in the far south, the small zamindaris, the Palegars, the small states in Andhra, in Tamil Nadu and in Karnataka, the incredibly fragmented Kerala political world of the seventeenth century where every time you cross a river, that is every 15 minutes, you meet a new state—all these states have their own way of thinking about why they exist and what the nature of kingship is. In all of these areas you can see there is a new idea of what politics is all about. It is there in Krishnadevaraya’s Amuktamalyada. He explicitly thematises it. So that is another area.

YB: So, in the home of a karnam (or karanika, title for a court administrative official) in some village, let us say, in 1600, in a salon, what do you imagine was going on? What texts were being read? What kind of cultural exchanges, political exchanges, stories were being told, music being heard?

DS: So, again in a kind of broad and generalising way, I think you could say that this is the new elite. There should be no doubt about it. These are elite formations. We are talking about very sophisticated audiences. These are people with at least some kind of knowledge of the traditions, that means they may not have learnt the Amarakosha by heart, but they know people who do know it by heart and they would have heard it coming from them. They will have some training in grammar, either Sanskrit grammar or the grammar of Telugu or Tamil or whatever it might be. They will have some familiarity with the great books, because these books are being intertextually quoted again and again by all the new books. They always have intertextual quotations which presume some kind of knowledge. They are educated, they tend to be what you might call some kind of middle class, I suppose, maybe not all of them. Because these texts have potentially a wide range of appeal. Actually we have evidence about these salons. We can say something about them. We know who were there, from a period a little later, from the nineteenth century Kaveri delta or the late nineteenth-century salons in Madras, we know who these people were. Some of them were nouveaux riches, they had gotten rich in an economy which had become cash-based; some of them had commercial contacts with people coming from outside, the foreign trade companies; some of them got rich because they carved out kingdoms in potentially very wealthy places, had the income again in cash, so they tended to be moneyed people, and they had leisure, that is another thing. These are people who had the leisure to read together one of the new Prabandham texts. Most of these Prabandham texts can be read, if you read every day, let us say, for three hours or two hours, you can recite or listen to an entire Prabandham usually in less than two weeks. That is a new thing also in South India for sure. So these are people who are able to come to have tea, or actually wine if it was in the evening. They had time to sit in the salon and listen to these texts some of which they might have composed themselves, among themselves, for themselves, for one another, maybe every day. We have verses that actually tell you that, that explain what the life of a literary aesthete man or woman about town was like in those days. There is another thing—since you mentioned the karnams, I think it is very possible these karnams indeed were consumers of the new literature and music and art. The karnams were literate not in the traditional sense—that is an oral literacy—but they also had graphic literacy. That, I think, is a new development, something which you see in many of these texts. Maybe most of the texts have sensitivity to the importance of the act of writing, to the shape of characters, and to the relation between the recorded, written text and the memorised text. And so the karnams were literate people.

YB: What would the linguistic situation be like? How many languages or which languages were spoken, understood and composed in these situations?

DS: Let us suppose, we are thinking about a specific place, let us say, Hampi, Vijayanagara Empire at its height, maybe ten years before it collapsed. There were ten good years because that is when the Vitthala temple, the most magnificent of all the Hampi monuments, was built. Let us imagine this period. Who were they? Some of them were amaranayakas—military commanders who were well-educated. Some of them were poets, as we know. Some of them were merchants, whose names we also know. We have some idea about who these late Kakatiyas or early Vijayanagara period people were.

They were multilingual people. I don’t think, among these groups and the literary salons that we were imagining, there were any monolinguals at all. They knew Telugu of course; they were also living in a Kannada-speaking area, they naturally knew Kannada; and they had to know some Sanskrit, they were not experts in Panini but they could understand Sanskrit. Some of them, you know, took pride in knowing Persian, for example, Srinatha. Only a hundred years before, Srinatha, in his introductory verses to Bhimakhandamu, a wonderful text, is talking about his patron who is exactly one of these elite people, and this patron could write nasta‘liq (a Persian calligraphy), he knew Persian as well, North Indian scripts, also Telugu and Kannada scripts. So I think that is a multilingual environment. I think that was largely the norm for the sophisticated, literary cultures in South India right up until the year 1956, which was a disastrous year in South India, because in 1956, the Indian states were reorganised, divided on a linguistic basis. You had a state for Tamil speakers, you had a state for Telugu speakers, and so on—the result of this is that, in a very short period of time, in seven or eight decades, in all of these states you have monolinguals. Maybe, say they are Malayalam speakers but they know a bit of English, or maybe a little more, and maybe a little Hindi, which they somehow pick up from the movies and from school, and maybe a tiny bit of Sanskrit. They really don’t understand Tamil, they don’t know Telugu or Kannada—these are like foreign worlds to them. It is a disaster. The old polyphonic and multilingual environment had been shattered except for the border zones, like Palakkad, where they are bilingual, say Tamil and Malayalam; or in Rayalaseema, where you have people who speak Telugu, Tamil and maybe Kannada. So there are vestiges of the old environment—multilingual, aesthetic and erudite environments—that are fast disappearing. It is a kind of a catastrophe.

YB: I want to know about music. It is not very usual that person who writes much so about texts is also fascinated by and is a connoisseur of music. But you are very much into Carnatic music, and want to write a book about it. You learned it—you sang it. When did you first come into contact with Carnatic music? And what did your body tell you at that time?

DS: Yes, true. It was a bodily experience. I can tell you exactly when. It was in July 1972. Eileen and I had just gotten married a few months back, and had come to India for the first time on a honeymoon tour. We were like backpackers. We didn’t have any money but somehow we managed. We were about to shift to England because I had decided, rather against my own instincts, that I was going to do a PhD in some South Asian field, actually in Tamil—again for accidental reasons, I settled upon Tamil. I wanted to see India before I went off to England to study. I just wanted to see what it felt like. So we came, and it was hot. It was July—hot and humid and overwhelming—and we liked it. We liked really almost all of it, I think we could say. But when we came to Madras—for me Chennai is still Madras, I can’t think of it in any other way—when we came to Madras, we stayed in the New Woodlands Hotel, which was then indeed quite new. About 100 m away from the Music Academy. It was love at first sight. Really, at first sight, we loved Madras. We loved everything about it. It was as if it had always been ours. For both of us. Eileen might give a slightly more nuanced description of this. Since you asked about the music, that is when we began. We went to the concerts and heard Carnatic music. Although it was strange to the ear as was Tamil, by the way. Tamil sounded not even like a human language. It sounded like, you know, some strange language of the birds or the gods. It was strange but somehow very compelling. We bought a few 78 LPs. That is what they had in those days. We brought them home in a suitcase. There were some Carnatic kacheris (concerts) and things like that. It moved me tremendously. The whole thing moved me. Everything about Madras was moving. We loved the food, we loved the people, there is some fantastic thing about them, even the weather, even though it was unbelievably hot and humid. Everything had that kind of dense, thick texture which is the texture of Madras. So that was, I think, our initiation into Carnatic music. And we came back to Madras in 1976 to live there. We lived there during the winter months—in Mandavelipakkam. So again through a series of coincidences, Eileen began to study Carnatic music. She is very musical. And she very rapidly went through the first three or four years of Carnatic exercises and scales that people learn, at the feet of a teacher, Thiruppur Ramu. She quickly began to sing varnams (a form of composition in Carnatic music repertoire) and then kritis (a form of composition in Carnatic music), and performed with her teacher in temples. They did not have common language. Ramu did not know English and Eileen did not know any Tamil. Somehow they communicated through the music. HearingEileen sing like that … those might be the deepest moments in my life. Also, I should say, my guru John Marr taught me Tamil. Among the many things he was expert in, one was Carnatic music, which may be even now—he is in his nineties—the central driving power in his life. Actually, he loved everything about the Tamil country and the Tamil language and Tamil people, but, above all, the music. So it was very natural that—I was four years with him—music was also a part of my own life. There is one other little autobiographical thing that maybe I should say, which is that when I was a young boy, between the ages of five and fifteen, those ten years, I was a violinist. Also learnt piano. But I was mostly connected to the violin, and that was the centre of my life. I wasn’t so good at it but I loved it. I was composing music without knowing very much. I listened to other sorts of music. I think that afterwards it got submerged under all kinds of things, rather you might say that the interest in music mutated into an interest in languages and their musicalities. I think it is the main thing that I look forward to and yearn for when I have to learn a language. I want the music of it. Also, in reading texts, I keep listening for the music, you know.

YB: You came back to Israel after doing your PhD in 1976. Ever since, you have been living in Jerusalem, and you basically, if you don’t mind me saying so, founded South Asian Studies in Israel. A major project—and when you look back at the project, what do you think?

DS: Above all, I think, I was extremely lucky. It was just some kind of amazing luck. The luck that allowed me to find my way to South India, Tamil, then Telugu and then the fact that the university [Hebrew University] wanted somebody to teach about India. It was a little bit easier in those days, I guess, university appointments, though still not so easy. But there was a job waiting for me. Also, at that time, India was a kind of periphery of the humanities at the University. So they wanted a person who knew something about India, and they recognised that Sanskrit was important. But otherwise, they left me and my colleagues who began to arrive pretty much alone. Prof. Alexander Syrkin came from Russia, and, later, students who got jobs, students who began with me and then came back and began teaching Tibetan like Yael Ben Tor or Yohanan Grinshpon who did a PhD in Indian Philosophy and then you. When you came back, that was the luckiest thing that ever happened to me in the academic world. So we were left to our own devices. Nobody interfered and nobody tried to tell us what we had to teach. Basically, there was no such thing as credits that are like some kind of currency today. Today if you go to the university, and a student registers, he gets a number of credits in his account like money, and all kinds of distortions take place because of that. In those days you could take as many courses as you wanted. If you did two BA worth of credits in your three or four years there, that was no problem. You will be able to keep these credits for the MA and, in fact, that was the norm. Most of the India students tended to be a kind of self-selecting group, people who were passionate about it and actually loved doing it and were very good at it. They learned all kinds of languages. There was very, very little interference from above and, I think, gradually it [South Asian Studies] became an important part of the Hebrew University. That is, the Hebrew University in its broader spectrum that includes the Institute for Advanced Studies, which is a very important unit. Sanskrit and Indian studies became part of the intellectual landscape and soon assumed their rightful place, which was waiting to happen in any case. Because the links between this place on the eastern shores of Mediterranean and India are very powerful links. So, I think that now along with Judaic studies and with classics, Assyriology, and the linguists studying many languages, Indian languages found a kind of home in Israel. On the one hand it is a bit of an unlikely story, but on the other hand, there is a natural quality about it. I was blessed with these fantastic students and colleagues.

YB: A lot of your works, in addition to writing all these books and regional essays, consisted of translating from Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu and other languages. Would you like to share a verse with us and offer a running translation?

DS: I can bring a verse from Naishadhiya, which is a challenge, just as an example of the kind of verse I like to work on. I spent a lot of my life translating things, often with Velcheru Narayana Rao and others and with you. I always say to my students that languages are usually impervious to translation. Even a very simple sentence like ‘I came to Moozhikulam to watch Kutiyattam’—if you say it in English, or if you say it in Malayalam, it is not the same sentence at all.

I will read a verse. I don’t like talking about the theory of translation. And every time I see a translated volume in which the translator has a long, boring introduction about the art of translation and how impossible it is, I know the translation will be no good. I know for sure.

This is from the Naishadhiya. Actually, you can open the Naishadhiya at random and any single verse that you pick, any one of them, is going to be a fascinating tour de force—some amazing verse. They are amazing because of the musicality that I was talking about. And also because of that unbelievably rich intertextual play that he brings to bear, and also because of the very weird and peculiar diction that he invented. So here is a verse that comes very close to what we were talking about before—about that bodily knowledge, that non-cognitive, extra-cognitive or meta- cognitive cognition.

So I will tell you the setting. This is the famous goose who is about to become a love messenger between Nala and Damayanti. And the goose actually offers a theory of speech, of language, of what he, the goose, can or cannot do. Nala is pleading with the goose to go to Damayanti and tell her that he, Nala, is her proper husband, and he is in love with her and all that. So Nala says this verse about why the goose is going to be the perfect messenger. As you can tell, they are having this conversation in very abstruse Sanskrit.

Here is the verse. It goes like this:

akhilam vidushaam anaavilam

suhridaa ca svahridaa ca pasyataam

savidhe ‘pi na suukshma-saakshinii

vadanaalankriti-maatram akshinii

Usually, Sriharsha’s verse, when you first hear it, you won’t understand anything. But when you hear it for the second or third time, then you crack it open, and it looks obvious and immediately intelligible. So, here, I will give you a rough translation of it.

Nala says to the goose, ‘Everything is lucidly perceived by those who see through the heart or through a friend.’

suhridaa ca svahridaa ca pasyataam

The opening now looks very clear.

akhilam vidushaam anaavilam

Akhilam—Everything. Anaavilam—is perfectly clear. Vidushaam—to somebody who can understand. Everything is lucidly perceived by those who see through the heart or through a friend.

So, the goose has become a friend.

Then he says: The two eyes that sit on our face, that can’t detect anything fine, suukshma, however close it comes, are there only for ornament.

You know, eyes look good, they see things but they can't see the subtlety.

YB: They look good on you.

DS: Yes, they look good on you, but even something that is in front of your eyes, you may not actually see it. You need some kind of luck to see it. You have to perceive it through your heart, or through the words of your friend or the presence of a friend. Now that allows you to actually know what you are looking at. I think that is an amazing statement of the thing that I was trying to suggest earlier about this other kind of knowing. It is nice to find it in Sriharsha’s verse. It is like coming to one of your friends.

YB: Thank you for talking to us and sharing some of your thoughts with us, and for all those conversations over the years. May they last many more years.

DS: May they last many more years. Thank you.