Ladakh is an open book of pre-Tibetan Buddhist art, mainly in the form of rock sculptures. Innumerable images of Buddhist deities and icons of varying sizes, intricately carved and engraved on rocks, are scattered all over the region. Most of them are found in the same spot and natural ambience of an era that once prevailed in Ladakh. These carvings are generally located in close proximity to a settlement, by a river, a stream or natural spring. According to historians, Buddhist rock sculptures dotting the landscape bear witness to the early introduction of Buddhism and Buddhist art in Ladakh from the Indian side, especially from Kashmir, before the Tibetan influence began in the region.[1]

Ladakh is one of the important centres of Buddhism. Colossal images, stray sculptures, rock engravings of Buddhist divinities are found in abundance in almost every part of Ladakh.[2] It was during the eighth century AD that the ruler of Kashmir, Lalitaditya, expanded his empire towards eastern India, and his contacts with this region led to the introduction of Vajrayana gods and goddesses in Kashmir.[3] Subsequently, Kashmir supplied skilled craftsmen, exported its craft and dispatched manuscripts (including illustrated ones) along with distinguished religious teachers throughout the region. One of the neighbouring regions that experienced the strong impact of Kashmir between the eighth and thirteenth centuries was Ladakh.[4] The results of this cultural fusion can be seen in some of the artefacts in Ladakh that come from other places, especially metalwork and wood carving.

It is important to note that the aesthetic traditions of Kashmiri art in Ladakh, which have roots in Gandhara art, should come as no surprise as geographically it is contiguous to Kashmir. We do get ample evidence that in the ‘Second Phase of Buddhism’, sculptures and colossal images are introduced in Ladakh region, largely extent during the seventh century and the evidence of this reveals that sculptural art is linked to Gandhāra.[5] Ladakh must surely have been subject to the rule of Lalitaditay Muktapida (AD 700–736). ‘It is to the 8th and subsequent centuries that we may attribute the Buddhist rock reliefs, which represent the most important traces of pre-Tibetan, i.e., direct Indian Buddhist influence in Ladakh.’[6]

Buddhist Rock Art Forms Found at Different Sites

The first of the entire series of Buddhist rock art in Ladakh is found at Drass, soon after crossing the Zojila Pass on the Srinagar–Leh National Highway. Drass is a part of the Kargil district of Ladakh, and its residents belong to the ethnic community of Dards or Brogpas who speak their own language called Shina. Drass is considered as one of the coldest human-inhabited regions of the world; the traditional houses here have a distinct architecture to suit the extreme temperature that dips to as low as minus 60 degrees Celsius in winter. While driving past the Drass region on Srinagar–Leh road, a row of Buddhist rock sculptures is sighted prominently on the roadside at Skitbu village. (Fig. 1) They stand there as sentinels of a bygone era when this route was presumably frequented by pilgrims, traders and Buddhist missionaries travelling towards Ladakh and beyond. From about the middle of the seventh century, the grand trunk route between Lhasa and Kashmir was frequented by travellers, and this paved the way for the models of Kashmiri art to travel to Western Tibet.[7]

The stone sculptures represented at Drass are Avalokitesvara[8], a six-foot-tall standing Maitreya, with three devotees depicted kneeling below, reaching up to his knees. On the left side of the head of Maitreya is carved a very small human figure, and to the right, there is a Sarada inscription. Another figure is that of a man riding a horse, wielding a sword in his left hand and the bridle in the right; there is a depiction of a human figurine and a lotus flower also. These sculptures are placed in a row next to the road and probably date to the eighth century AD.[9] A shelter has now been built over them for protection.

Some 65 km from Drass, on the outskirts of the densely populated Shia town of Kargil, are repositories of perhaps some of the world’s most remarkable and largest Buddhist images of the seventh to eighth centuries. (Fig. 2) The tallest of them is a 40-foot-tall magnificent rock sculpture of Maitreya in Kartse hamlet of Suru valley, an extensive lush green valley south of Kargil town. The colossal statue on a hill overlooks a cluster of mud houses and a mosque at the foot of a glaciated mountain; in between flows a stream of sparkling water. While the existence of a Buddhist image in the Shia community settlement is modestly recognised by the community living here, the local governing body, Kargil Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC), has plans to develop the site for tourists.

A little further down from here, barely a few kilometres, the Kartse stream confluences with the Suru River, this forms the main water source for the large population living in the Suru valley and Kargil town. Immediately after crossing the bridge on the Suru River, close to the confluence point, some distance ahead from Sanku towards Kargil town, there is a roadside boulder under a tree that bears fine engravings of Padmāpani Avalokitesvara flanked by two goddesses; other surrounding images include a horse, umbrella and stupa amongst others. Some are a little more difficult to discern. The style and finesse of engravings of the goddesses flanking the main image are akin to the Kashmiri style of art. Small simplistic images (three of them) at the foot of the main engraving appear as lay devotees dancing, probably the locals in their traditional attire.

In the Soth area adjoining Kargil town towards the north, in the poplar grove of Tumail hamlet hides another strikingly imposing image of Maitreya Buddha carved on the rock surface of a mountain range that forms the dividing line between the war zone of Battalik and Pashkyum valley. (Fig. 3) There is an interesting episode that the locals (Shias) associate with this Maitreya. They say, the trees in the immediate vicinity of the deity mysteriously survived the continuous three-years drought in the area around the year 2000, while all the other poplar trees in the area perished.

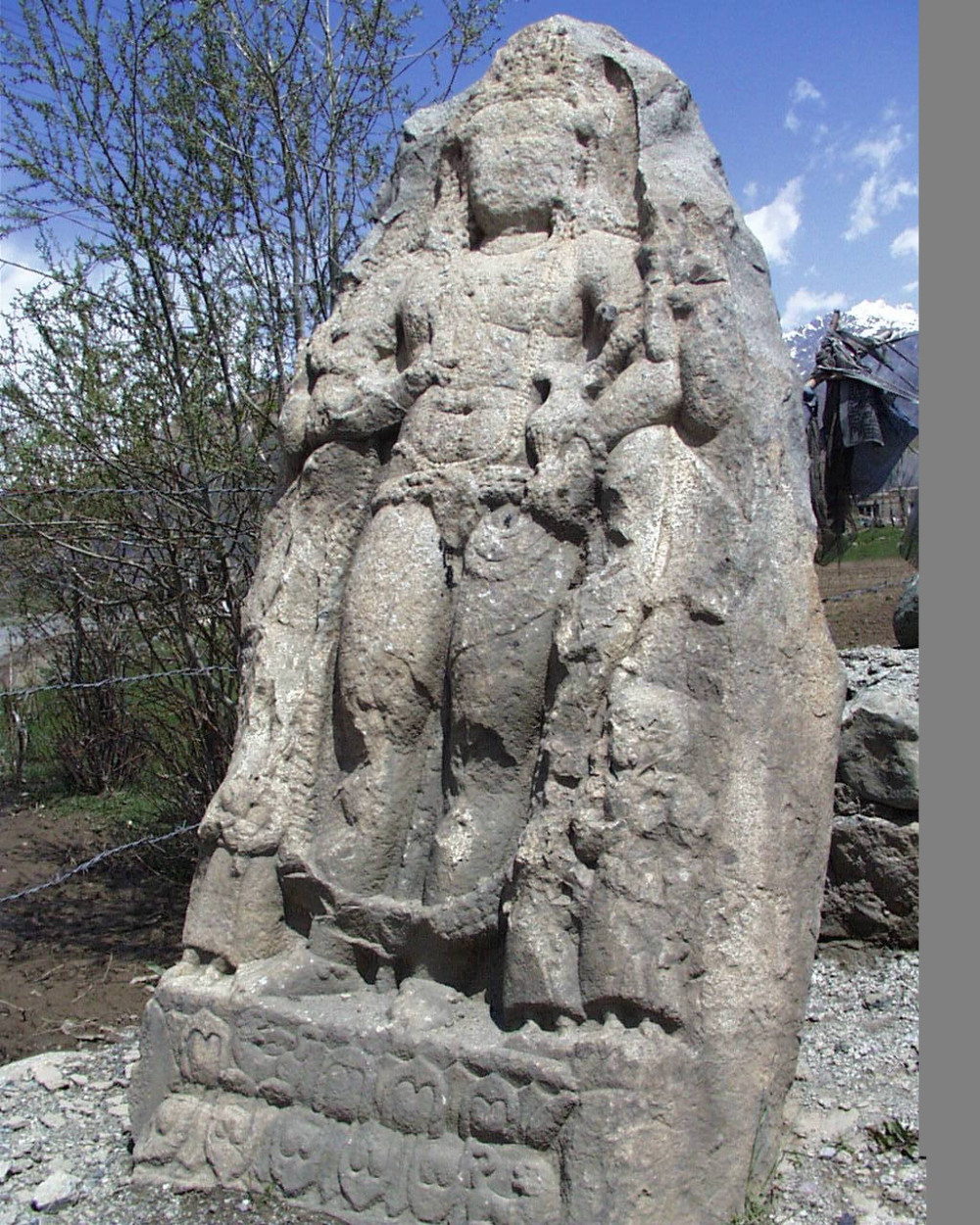

In the Shia-dominated Kargil district, Mulbekh is the first Buddhist village on the Srinagar-Leh road after Pashkyum. Captain W. H. Knight, a British officer who travelled all the way to Ladakh from Pune in 1857, describes the Pashkyum inhabitants as Buddhists in his travelogue. He writes, “The religion seems to be a mixture of Buddhism and Mahomedanism —the latter on the decrease as we get farther into the country. The dress assimilates to the Chinese.”[10] Today, there is not even a single Buddhist family in Pashkyum, however, not very far from here (about 20 km away), in the Wakha-Mulbekh area there is a considerable Buddhist population. The most popular rock sculptures in Ladakh and by far the largest after Kartse Chamba is the Mulbekh Chamba, a grand statue of Maitreya carved on a huge wayside boulder, situated at the beginning of Mulbekh village on the Srinagar-Leh road. It attracts Buddhist pilgrims from all over Ladakh, and for the locals, Chamba holds a great cultural significance as well. T Nurboo, a senior member of the community, says, ‘The annual Mentok Stanmo (flower festival) in our village begins with the eventful ceremony of Thugs spar (banner hoisting) atop the Chamba and rituals performed before it.’ Once a controversy gripped this statue over its rightful overseer between two dominant monastic groups in Ladakh, and the matter was resolved in favour of the Hemis monastery. The Mulbekh Maitreya has been a controversial figure, with some scholars disputing it is not Maitreya Buddha (Chamba) but Avalokitesvara (Chenrezig). But the local residents of Mulbekh are firmly of the view that this is Maitreya Buddha. There are many signs that affirm the local view—the Maitreya Buddha is embellished with rich ornaments as is common, in his right hand he holds the stalk of the lotus (Nagakesra) flower and on his head, a small stupa adorns his crown.[11]

In the region of Zanskar, especially Padum, there are again numerous rock sculptures. Though the Zanskar valley is a subdistrict or tehsil of the Kargil district, it is much larger in size than the rest of Kargil, and the landscape is overwhelmingly dominated by Buddhist monasteries and sacred Buddhist sites, including ancient rock sculptures. Buddhist rock carvings and reliefs of varying sizes are found in Sani, Padum, Stongde and in places towards Lungnag valley including Shila, Pipcha and Munay. Gyalwa rig-nya (five Dhyani Buddha rock relief) and Maitreya Buddha sculpture of Sani are among the prominent ones. Dur Khrod bDechen brdal at Sani in Zanskar is considered one of the eight great cemeteries (Dur Khrod rGyat) in India. The imposing sculpture of Maitreya has nine smaller sculptures on its right and left sides. Those days the site served as a holy funeral pyre for even the people of Kashmir. Locals still use it, but the main pyre stone has been shifted to the nearby riverside. (Fig. 4)

After Mulbekh Chamba in the Kargil district, it is curious to note that there are few examples of rock art along the way to Leh town. It is only in Leh itself, after travelling nearly 200 km, that one can again find examples of rock art from this period. Except for a rather simple carving of a Buddhist deity with lay devotees on an interesting rock formation in Taru village (20 km short of Leh town), one hardly comes across any rock sculpture all along the way from Mulbekh. There is, though, a fine pre-Tibetan Buddhist rock relief on the way to Hunder in Nubra valley from Phyang village, which is considered as one of the important alternative routes to Central Asia. There is a major route from Phyang to Nubra via Hunder Dok. Phyang–Nubra Pass is one of the important passages from Ladakh to Khotan, connecting the historical silk route. On the Hunder–Phyang Pass, just before approaching Hunder village, there is a Maitreya rock relief near the river, which witnessed the introduction of Buddhism in Nubra valley. The time period of the Hunder Maitreya is sixth to seventh century. Almost the same type of sculpture of Maitreya is also found from Panamik and Tirith dated eighth–ninth century (IAR 1992-93; 36-37). Rock-cut sculpture of Yensa Maitreya dates to the eighth-ninth century AD.

Beyond Leh, on the Leh-Sakti via Wari-la to Nubra, on to the old Khotan route, which was once claimed as the main passage through Ladakh, there is substantial evidence as this entire stretch is dotted with rock sculptures of different Buddhist deities; the sheer number of these rock sculptures make this area a veritable garden of early Buddhist rock art. Tangyar, the first village after crossing Wari-la pass has a simple rock art close to the village school. But perhaps the biggest in the Leh district is the one on a rolling hill across the stream of Digar village. Intricate reliefs on all sides of about a 12-foot tall rock have, among others, a sword-wielding deity, which is generally identified as Manjusri, the Buddha of Wisdom. (Fig. 5)

The most intricate carving in and around Leh town is in Changspa hamlet close to Leh bazaar. A tapering rock with images of Avalokitesvara, the Buddha of Compassion, and Maitreya Buddha (Chamba), the Future Buddha, on two reverse sides and a stupa on the third is located in the heart of the old settlement area of Changspa. This masterpiece, considered to be created between the seventh to tenth centuries has survived the trials of time and stands with pride in the backdrop of the Gomang Stupa (also known as the stupa of many doors). Above the Maitreya image are two flying gandharvas and a lay devotee below. (Fig. 6) Leaning on the main image is a carving of a small Maitreya in abhaya mudra. A unique figure below the Avalokitesvara image is a deity with a horse above or on his head—a feature associated with the powerful Buddhist deity Hayagriva, locally known as Rta-mgrin (rta is horse in Bodhi). This deity originated as a yaksha attendant of Avalokitesvara or is considered as a wrathful manifestation of him.

There are two other rock carvings in the premises, however, both have undergone severe weathering, as a result the images are not so clear. Another one, with a three-pointed crown, lies in a narrow alley close by. One of the common features found in early Buddhist rock sculptures, particularly in case of Maitreya, is the three-pointed crown or diadem. Similar figures on a rock survive in the backyard of Oriental Guest House in Changspa, at the foot of Rebuk hill. In the old town of Leh, the newly renovated Sankar Labrang, a small two-storeyed traditional building, houses few rock reliefs. The entrance to Leh Palace from Chutay Ranthak, one of the narrower streets in the town, and in the premises of some Muslim houses right below and behind the palace there are rock images dating to the same period. Similarly, on the way to Sankar Monastery, a shelter houses several painted images on rocks of different sizes, which have been shifted from their original positions. Another early rock carving is located at the beginning of Gyamtsa valley near Gonpa hamlet, it is locally known as Lchangri Gyamo. This area has traces of one of the earliest human settlements in Leh along the main glacial stream, along with the earliest one at Skara much further downstream.

Skara, a suburb situated south of Leh, near the present airport, has a standing Maitreya in the abhaya mudra position. It lies adjacent to a round stupa of a much later period in the backyard of the old traditional house of Leh-pa family. Again, this rock has images carved on all its sides. Little further down from here, next to the Karpotok house, is another fine rock-carved image of Maitreya lying half-buried under the ground, above his head are flying Gandharvas. Elderly members living in the vicinity of this rock engraving remember there used to be a shelter over it earlier, and it is considered very sacred and powerful. The owner once suffered an injury in an attempt to uncover the buried part of the image, and since then locals avoid fiddling with it. (Fig. 7)

The Gomang Stupa behind Shey Palace also has a rock relief of an image holding a stalk of a lotus flower. Even though it is difficult to discern the identity of the image, the style is more akin to Kashmiri art than Tibetan, unlike the nearby carvings of the Five Dhyani Buddhas on a large flat rock below Shey Palace, at the foothill along the Shey lake marshes. The Five Tathagata carving is associated with the advent of Tibetan Buddhism in Ladakh and it is dated around the ninth and tenth centuries. There are other stray carvings found along the lakeshore at the foothill, which seem to be of earlier origin. A little further away at Shey Dorjey Chenmo temple, there are more early rock images (all about a meter-high) provided with sheltered protection in the compound and the ones kept just outside the temple. The first Tibetan King of Ladakh, Lhachen Palgyigon, chose Shey (Shel) to be the capital of Ladakh and built a fortress here on the hill.

Moving on to the next village, Thiksey, a worn-out rock carving lies beside a water channel through a hamlet below Thiksey monastery. The next set of rock carvings after Thiksey is traced to Sakti village, at a distance of 30 km between the two villages. This is probably because there are hardly any settlements along the left bank of the river Indus in between Thiksey and Sakti. It is pertinent to point out that the presence of any rock sculpture along the right bank of the Indus is largely unheard of, this may be indicative of the fact that the trade routes corroborate with the existence of rock carved Buddhist images along them. Accordingly, the route has turned left of the Indus at Kharu towards Sakti village, thereby further on to Shyok River belt crossing the Wari-la pass.

Another left-turning point from the Indus is at Igoo village, where the presence of elaborate rock sculptures and even bigger and grand sculptures in Digar village in Shyok belt of Nubra valley reinforces this theory of Silk Route passage through Ladakh and early Buddhist rock sculptures along it. These carvings are found only in the western parts of Ladakh, Igoo being the easternmost valley with such remains.[12] The absence of such carvings beyond Igoo, and the continuum of its existence all through western Ladakh leading up to Central Asia provides a rich source of cultural and religious history within a regional expanse, and a trade destiny prior to the advent of Tibetan Buddhism. In this manner rock arts of Ladakh represent an epoch in the different historical phases this trans-Himalayan region witnessed.

Notes

[1] Spalzin, ‘Analytical Study of Sculptures of Ladakh with Preliminary Account on Kashmir Sculptures,’ 84.

[2] Francke, A history of Western Tibet, 80.

[3] Singh, Himalayan Art, 62.

[4] Malla, Sculptures of Kashmir, 96–97.

[5] Spalzin, ‘Analytical Study of Sculptures of Ladakh with Preliminary Account on Kashmir Sculptures.’

[6] Snellgrove and Skorupski, The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, 6.

[7] Malla, Sculptures of Kashmir, 97.

[8] Snellgrove and Skorupski, The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, 9.

[9] Francke, A History of Ladakh, 52.

[10]Knight, Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet, 151.

[11] Spalzin, ‘Analytical Study of Sculptures of Ladakh with Preliminary Account on Kashmir Sculptures.’

[12] Devers, ‘Archaeological Ladakh,’ 109.

Bibliography

Archaeological Survey of India. ‘Explorations and Excavations: Jammu & Kashmir.’ Indian Archaeology and Review 1992–93: 34–37.

Drew, Frederic. The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account. London: E. Stanford, 1875.

Devers, Quentin. ‘Archaeological Ladakh: Recent Discoveries Redefining the History of a Key Region between the Pamirs and the Himalayas.’ Central Asiatic Journal 61, no. 1 (2018): 103–132.

Dorjay, Phuntsog. ‘2 Embedded in Stone—Early Buddhist Rock Art of Ladakh.’ In Art and Architecture in Ladakh: cross-cultural transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakoram, edited by Erberto F. Bue and John Bray, 35–67. Boston: Brill, 2014.

Francke, August Hermann. A history of Western Tibet. SW Partridge and Company, 1907.

Francke, August Hermann. History, folklore & culture of Tibet. New Delhi: Ess Ess Publications, 1979.

Francke, A. H. A History of Ladakh. Srinagar: Gulshan Publishers, 2008.

Francke, A. H. Antiquities of Indian Tibet - Vol. I. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India Publications, 1994.

Joshi, M. C. Indian Archaeology 1988–89: A Review. Delhi: Archeological Survey of India,1993.

Malla, Bansi Lal. Sculptures of Kashmir, 600-1200 AD. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1990.

Moorcraft, William. Travels in Himalayan provinces of Hindustan, Punjab, Ladakh, and Kashmir. Read Books Ltd, 2013.

Knight, William Henry. Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet. London: R. Bentley, 1863.

Luciano, Petech. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 A.D. Rome: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1977.

Spalzin, Sonam. ‘Analytical Study of Sculptures of Ladakh with Preliminary Account on Kashmir Sculptures.’ Pakistan Heritage 432, no. 4154 (2016): 1–16.

Singh, Madanjeet. Himalayan Art: Wall-painting and sculpture in Ladakh, Lahaul, and Spiti, the Siwalik Ranges, Nepal, Sikkim, and Bhutan. Melbourne: New York Graphic Society in Greenwich, Conn., 1968.

Snellgrove, David L., and Tadeusz Skorupski. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh. Boulder: Prajña Press, 1977.